Bison Bowls, Frybread, Indian Tacos: the Flavors of CSUN’s Powwow

The soft dough is kneaded, pressed flat and set in a deep pan of bubbling, sizzling vegetable oil. The warm, sweet scent of freshly baked bread permeates the air as the dough cooks through. When it’s ready, the Navajo frybread puffs up and crisps to a golden brown, and the cook pulls it out of the pan with tongs, lays it on paper towels to soak up the excess oil, sets it on a plate and finally hands it over, hot, to a long queue of eager customers.

Navajo frybread. Photo courtesy of Susie Yellowhorse Jensen.

Crispy on the outside and chewy on the inside, with a taste akin to funnel cake, frybread is an American Indian staple. It’s a crowd favorite at the annual CSUN Powwow, selling hundreds in just one day.

Powwows are social gatherings for North American Indian tribes whose traditions date back centuries. Tribal members and loved ones sing, dance in traditional regalia and celebrate their culture. As in all cultures, food is central.

The 36th Annual CSUN Powwow on Nov. 30, hosted and organized by the university’s American Indian Student Association and the American Indian Studies Program, will feature both traditional and nontraditional American Indian food items.

Traditional American Indian food consists of dishes made from the agricultural staples of each tribe’s region, such as beans, corn and squash, as well as livestock hunted and reared by the people. This history produced beloved dishes such as mutton stews from the sheep of the Navajo, Three Sisters stew and the various bison dishes from the Plains Indians. Other dishes were developed out of necessity as indigenous peoples were forced from their native lands into unfamiliar territories, where they had to adapt to lands that yielded different ingredients or where they met other cultures whose recipes intermingled with their own.

The CSUN Powwow features a large food stand for attendees to sample and enjoy freshly made frybread. In the past few years, organizers have invited Susie Yellowhorse Jensen, from the Navajo tribe, to supervise students in selling her delicious Navajo frybread.

The CSUN Powwow food tent serves freshly made frybread and Indian tacos every year. Photo by David J. Hawkins.

Made with just seven ingredients — flour, shortening, milk, salt and water for the dough, baking powder to leaven it, and a choice of powdered sugar or honey to top it off — Navajo frybread can be devoured in a number of ways. It can be eaten by itself or with toppings, including beef or beans on the savory side. For those with a sweet tooth, it can be served up with strawberries, whipped cream, honey or preserves.

“It’s the kind of food that you know isn’t really good for you, but you enjoy it because it’s festival food and you’re at the festival, having a good time,” said CSUN professor Scott Andrews, director of the American Indian Studies Program within CSUN’s College of Humanities.

A Taste of Home

This year, the CSUN Powwow will offer a brand-new food stand run by Claudia Pacheco and her food business, FryBread Hut and Indigenous Burritos. The “indigenous burrito” will be prepared on-site with bison — the common protein consumed by Native Americans before American bisons were hunted to near extinction near the end of the 19th century — filled with beans, lettuce, tomatoes and cheese, then wrapped in a handmade tortilla. This new stand will also serve bison bowls, a salad with bison meat.

The Indian taco. Photo courtesy of Susie Yellowhorse Jensen.

The most sought-after dish at the CSUN Powwow is the Indian taco. Originally called Navajo tacos, the dish sprang from the Southern California melting pot — a mashup of frybread and Latinx specialities. It’s been embraced by other tribes as well, said Yellowhorse Jensen. The frybread plays the role of the tortilla, piled high with shredded lettuce, diced onions, green chiles, sliced tomatoes and grated cheddar cheese — with optional sour cream topping. It can be eaten rolled up or open-faced, with a fork.

Want one? Get in line. Getting your hands on an Indian taco at the CSUN Powwow means lining up line with dozens of people, Yellowhorse Jensen said. The stand typically goes through four to five 25-pound bags of flour in one day. That’s about 400 tacos.

Even when it poured during the 2016 CSUN Powwow, Yellowhorse Jensen said, “people stood in line, in the cold, in the rain — for a taco!”

American Indians seeking a taste of home aren’t the only ones standing in line for the fresh frybread. Yellowhorse Jensen said even powwow first-timers smile broadly after taking their first bite.

“They would go, ‘What is this? It’s so good. Where can I get more?'” she said.

Nontraditional Traditional Food

The Yellowhorse Frybread & Indian Tacos tent attracts a line of customers at the CSUN Powwow. Photo by David J. Hawkins

Although frybread is a common menu item today, the question of whether frybread is a traditional or nontraditional food is not clear-cut.

“Especially on reservations today, [frybread] is considered a part of weekly life for the natives, wherever they are from,” said Raven Freebird, president of the American Indian Student Association, “but the roots are not so beautiful.”

In 1864, the United States Army forced thousands of Navajos from Arizona out of their native lands and onto the 300-mile “Long Walk” to the Bosque Redondo Reservation at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, where the federal government kept them imprisoned for four years. Given nothing but white flour, processed sugar and lard to eat on the reservation, and after their livestock were wiped out by white settlers and troops — and their new land in New Mexico unable to support their conventional bean and vegetable crops — the Navajo made the most of the resources they had.

An Indian taco in Monument Valley. Photo by Lee Choo.

Today, instead of lard and coarse flour, the refined Navajo frybread is typically prepared with vegetable oil and fine-ground wheat flour.

However, Yellowhorse Jensen said, she still considers frybread an important part of her tradition. Despite its dark history, the recipe and its evolution has been passed down through her family, she said. Yellowhorse Jensen learned how to make frybread from her grandfather, and the recipe has been passed down through generations.

“In a way, it’s [non]traditional traditional food,” she said. “Every Navajo generation, we have it with our chili beans, the mutton stew … it has become a staple.”

A Thriving Culture

Not only the cuisine, but many other aspects of American Indian culture have evolved and blossomed, Andrews said. “As American Indian people adapted to their changing world, their cultural events have evolved as well,” he said.

Even the way powwows are celebrated in Southern California is “a 21st-century phenomenon” and a “blending of very old musical and dance traditions with very contemporary influences,” Andrews said.

Whether it’s the creation and adoption of certain dishes or the refashioning of cultural festivities, these changes showcase a community and culture that is alive and thriving, he said.

“Enjoying [frybread] in powwows today is a way of embracing something that was once negative and turning it around into something positive,” Andrews said.

Event Info

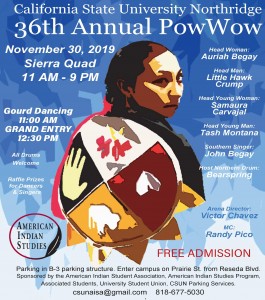

The CSUN Powwow is one of the largest and longest-running powwows in the San Fernando Valley and draws approximately 300-500 members of the community. The 36th Annual CSUN Powwow will be held Saturday, Nov. 30, at the Sierra Quad (open space in front of the CSUN library) from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. Grand entry, during which all dancers enter the arena in their regalia, will start at 12:30 p.m., beginning with a blessing and songs led by representatives of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, the indigenous people of the San Fernando Valley, and their president, Rudy Ortega Jr.

Event flyer for the 36th Annual CSUN Powwow. Courtesy of Scott Andrews.

Admission is free and open to all. Visitors with vehicles are advised may park for free at the B-3 parking structure. To access B-3, enter Prairie Street from Reseda Boulevard.

For more information, call (818) 677-5030 or email csunaisa@gmail.com.

experience

experience