Nutrient Pollution Runoff Makes Ocean Acidification Worse for Coral Reefs

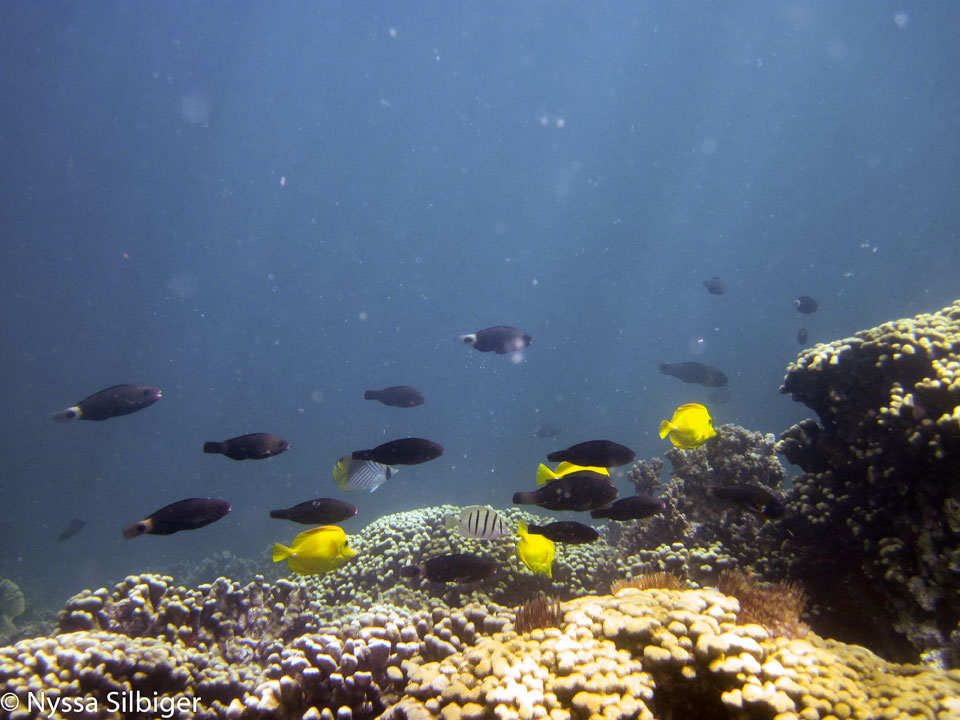

Nutrient pollution runoff from the land may be accelerating the negative impact global ocean acidification is having on coral reefs, according to CSUN biologist Nyssa Silbiger. The coral reef, above, is in Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, where her research was conducted. Photo credit Nyssa Silbiger.

Nutrient pollution runoff from the land — whether from sewage, farm fertilizer or the aftermath of a rainstorm — may be accelerating the negative impact global ocean acidification is having on coral reefs.

This is according to a new study by a team of researchers, including California State University, Northridge assistant professor of biology Nyssa Silbiger, recently published in the “Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Science.”

Coral reefs play a critical role in the economy and human welfare, including food security and shoreline protection to coastal communities. However, for coral reefs to thrive, the coral must be able to grow and reproduce at a faster rate than they are being destroyed.

As coral reefs struggle to survive the effects of ocean acidification, Silbiger said, the addition of nutrient pollution “inhibits the coral’s ability to utilize the natural building blocks of coral reefs.”

CSUN biology professor Nyssa Silbiger, right, and her colleague Megan Donahue of the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology are collecting water samples during the experiment. Photo credit Henry Shiu.

Silbiger, lead author on the study, noted that there is “a long history of examining the impacts of nutrient pollution and ocean acidification on coral reefs. However, little is known about how these two stressors interact and influence coral reef ecosystem functioning.”

Prior research showed that stressors associated with human-derived carbon dioxide emissions, such as ocean acidification, are shifting coral reefs toward net loss. The new study, “Nutrient pollution disrupts key ecosystem functions on coral reefs,” showed that nutrient pollution — the addition of nitrate and phosphate — could make coral reefs more vulnerable to ocean acidification and accelerate the predicted shift from net growth to overall loss. The pollution can come from leaking septic tanks, errant sewage, runoff from agribusiness and farms, fertilizers used by gardeners or runoff from a heavy rain.

As part of the study, the researchers, who included students and faculty at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Rhode Island and Scripps Institution of Oceanography, continuously added nitrate and phosphate to aquariums housing different components of the coral reef community, including corals, seaweeds, dead reef rubble or sand. They compared this with an experiment mimicking natural systems containing all the same components of the reef community. Then they measured critical “ecosystem functions” of coral reef communities — calcification, dissolution, photosynthesis and respiration.

“We showed that nutrient pollution decreases overall reef growth and disrupts the natural chemical dynamics on coral reefs,” Silbiger said. “In nutrient-polluted seawater, calcifiers were less able to capitalize on the dissolved compounds that make up the building blocks of coral reefs. Nutrient pollution reduced calcification rates — a measure of how quickly reef builders are creating the skeletal framework — nearly tenfold in waters that would otherwise promote reef growth, and enhanced both skeletal dissolution and the growth of seaweed competitors.”

Silbiger said the study raises questions for coastal communities around the world as they consider the impact of what they do on land on the vital coral reefs — which help protect their shoreline and often support a tourism industry — that sit just offshore.

“Hopefully, the study will help government agencies and local stakeholders make more informed decisions,” Silbiger said.

experience

experience