Africana Studies Week Celebrates the Department’s Historic Founding

California State University, Northridge celebrated the 47th anniversary of the birth of its Department of Africana Studies with an open house and keynote lecture during Africana Studies Week, from Oct. 31 to Nov. 4.

The week commemorated the department’s historic founding in 1969, when CSUN — then called San Fernando Valley State College — was nothing like the multiculturally inclusive and highly diverse campus it is today. In 1967, the college had just 23 black and seven Latina/o students, representing about 1 percent of the student population.

Establishing the department was a hard-fought battle, according to Africana studies professor Cedric Hackett.

“We commemorate the sacrifice students made, requesting an increase in institutional diversity to include administrators, faculty and students of color, and bring ethnic studies programs to life,” Hackett said. “A lot of students who protested in the administration building did some jail time, anywhere from three months to 25 years.”

The 1968 movement demanding institutional support for black students was a joint effort between black students, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the United Mexican American Students (UMAS), now known as Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (M.E.Ch.A.). SDS and UMAS helped collect the signatures needed to create the BSU and fuel their mobilization efforts, and, one year later, UMAS put forth their own demands for Chicano and Chicana students.

One of the triggers for the push to demand action from the administration was a violent altercation between a black CSUN football player named George Boswell and white coach, Donald Markham, on Oct. 18, 1968. During one of the football games, Markham grabbed Boswell — one of only three black members of the football team — by the neck and kicked him in the groin. Boswell took off his gear and quit on the spot. Players from the opposing team, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, harassed the black players. When the black players went to Markham to confront him, Boswell’s white teammates came to the coach’s defense.

One week later, on Nov. 4, about 60 BSU students gathered outside the athletic director’s office for a meeting. When the meeting proved unfruitful, the BSU group walked to the administration building (now known as Bayramian Hall) to demand a meeting with the college’s acting president, Paul Blomgren. According to historical accounts, the BSU group took over the fifth floor of the building and moved more than 30 staff members into a room and threatened to detain them until their demands were met.

The BSU protesters located Blomgren and made a list of 12 formal demands. The core of their demands included the creation of a black studies department, the recruitment of 500 black students a year to increase diversity amongst the student body, the recruitment of black faculty and tutoring services (run by black students) for black students.

Hackett said the founding of the department was especially unique because of the level of student involvement.

“Students had a 50 percent stake in the development of curriculum, making sure to have a community component,” Hackett said. “They had a say in faculty recruits and demanded that the department be headed by a black man.”

Today, students in Africana studies say they benefit from the rich culture and history of activism in their department..

Senior and Africana studies major Jovon Johnson said the department helps to actively combat institutional racism.

“Africana studies has taught me how to critically think and analyze social constructions and theories at a high level,” Johnson said. “[Africana studies] is vital to filling the many gaps that are otherwise overlooked by our school systems and helps remove social stereotypes, improve understanding of world history and most importantly, increases overall confidence of students.”

Junior Ayanna Joshua, who double majors in Africana studies and psychology, said Africana studies has helped her personal development and secured her identity.

“Prior to coming to college, I had very little knowledge on myself or my culture,” Joshua said. “Black history was rarely taught throughout my K-12 education and when it was, I was given false information. Africana studies has become a safe haven for me and has taught me self-worth. It has allowed me to appreciate my culture and my black brothers and sisters. I am culturally awakened because of Africana studies. My experience on the campus of CSUN would not be the same without Africana studies.”

Senior MaRonda George, a double major in Africana studies and child development, said the department inspires students to become leaders.

“Africana studies is more than a department,” said George. “Our courses are more than just classes to take for GE (general education) credit. This department breeds leaders and ignites a flame in its students, because once you are aware of who you are, who you were, where you come from and where you could go, there’s no way that fire can be blown out. There’s no way you can graduate CSUN and not want to serve your community in some shape or form.”

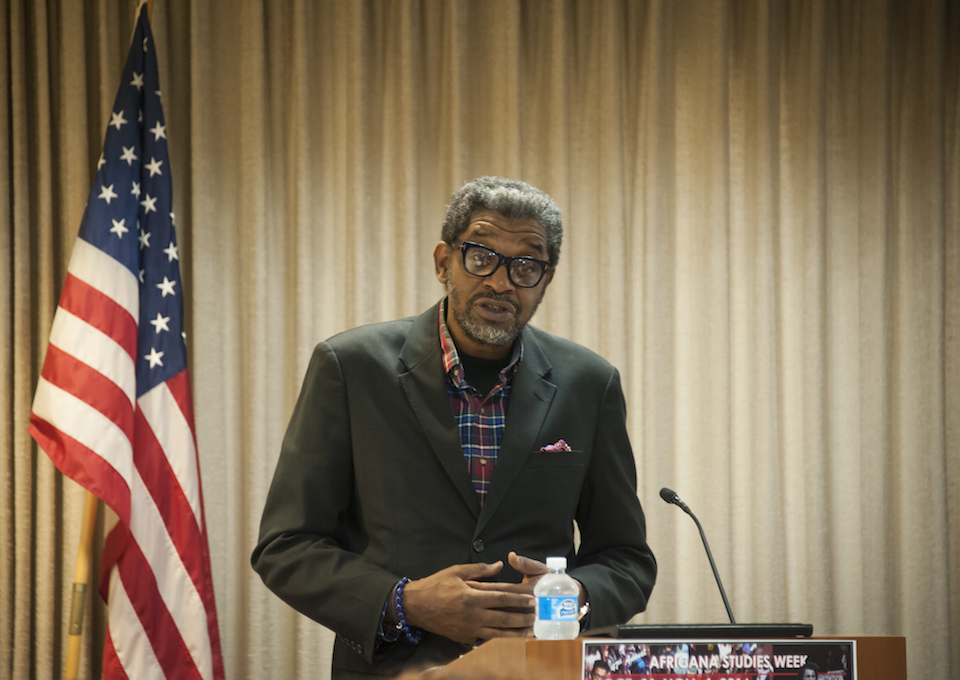

At the Africana Studies Week keynote lecture on Nov. 2, speaker Anthony Samad, professor of African-American studies at East Los Angeles College and the author of REAL EYEZ: Race, Reality and Politics in 21st Century Popular Culture and other books, talked about the notion of “post-racial America,” the 2016 election, race in popular culture and the importance of critical thinking among students.

“One of the things you will be asked to do as you evolve as scholars, as artists, contributors to the larger society, is to construct your own view of the world and resist conforming to the dominant culture’s view of the world,” Samad said. “Dominant culture would have you believe we live in a post-racial society. Part of scholarship is inventing your own theories [and] being able to sustain those theories in the context of societal reality. So whoever came up with ‘post-racial’ … their theory is not holding up.

“You’ve got to remain true to yourself.”

experience

experience