CSUN Prof Explores the ‘Darker Side’ of Chocolate’s History

Chocolate is so much more that a gift for Valentine’s Day. CSUN history professor Patricia Juarez-Dappe said chocolate also provides lessons in understanding larger historical processes, such as Mesoamerican civilizations, colonialism, the trans-Atlantic slave trade and 20th century human trafficking, and the Industrial Revolution. Photo by gustavomellossa, istock.

As Valentine’s Day approaches, a gift of chocolate can communicate so much — from friendship and affection to romance and love.

For California State University, Northridge history professor Patricia Juarez-Dappe, chocolate also provides lessons in understanding larger historical processes, such as Mesoamerican civilizations, colonialism, the trans-Atlantic slave trade and 20th century human trafficking, and the Industrial Revolution.

Patricia Juarez-Dappe

“Chocolate is the go-to special treat for so many of us,” said Juarez-Dappe, who teaches a class on the history of chocolate. “Some people like dark chocolate. For some people, milk chocolate is their favorite. Personally, I like to enjoy a piece of white chocolate to pick me up when I am feeling particularly depressed. But few people realize how much something as simple as chocolate — something nearly all of us enjoy, yet take for granted — can teach us about the history of colonialism, the spread of capitalism and the impact of marketing on our behavior. A piece of chocolate can be delicious, but it also has a dark side.”

Although the Olmec of early Mesoamerica are believed to have been the first to cultivate cacao, the tree whose seeds are used to create chocolate products, it was the Maya who were credited with the first recipe for chocolate and bringing it into a “high art,” Juarez-Dappe said.

“Among the Maya, cacao and chocolate had a direct connection with the divine and played a significant role in the transition to the afterlife,” she said. “Chocolate was drunk by the elite and shared with people of all classes during certain celebrations, feasts and important rites of passage. The Mexica (rulers of the Aztec Empire) inherited the habit of chocolate drinking from their Mesoamerican ancestors. For them, the drink was central to displays of political power, and its consumption was an essential mechanism to reinforce social prestige and political influence.”

In Mesoamerica, Juarez-Dappe said, cacao served both ritual and practical purposes, including being used as medicine, tribute and currency.

Many narratives claim the first European encounter with chocolate occurred when Hernán Cortés met Moteuczoma during the Spanish expedition that led to the fall of the Aztec Empire. Juarez-Dappe said that honor goes to Ferdinand Columbus, son of explorer Christopher Columbus, who wrote about cacao in the very early 1500s.

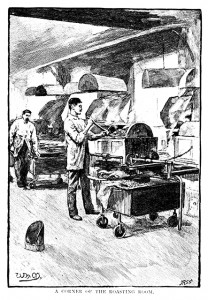

An 1892 English illustration of men working in the chocolate roasting room. Illustration by artist William Henry Margetson, iStock illustration

It wasn’t until 1544, when a delegation of Kekchi Maya arrived in Europe bearing gifts, including chocolate, that the Spanish Crown tasted chocolate for the first time. The first shipment of chocolate to Europe followed a couple decades later.

“Initial responses to chocolate in Europe were mixed,” Juarez-Dappe said. “The Spanish Crown took on the habit of drinking chocolate very soon, as did the conquistadors in the Americas. But not everyone responded the same way. Many in Europe rejected the drink, not just because of its taste, but many because of its association with the indigenous peoples.”

She noted that many of the colonizers, including missionaries from the Catholic church, were hesitant to adopt the foods and habits of those they were colonizing.

“It was considered ‘going native,’ which was very much looked down upon,” Juarez-Dappe said. “To make it acceptable to European consumers, medical treatises reconciled the curative qualities of cacao and chocolate, arguing that consuming chocolate would keep the humors in one’s body ‘balanced.’”

To make chocolate more palatable, Europeans added milk, sugar, almonds and spices such as cinnamon and jasmine, and by the 17th and 18th centuries, chocolate consumption took off. With demand for chocolate increasing, cacao production in the Americas grew.

“Europeans established plantations in continental Latin America and the Caribbean,” Juarez-Dappe said, adding that in Brazil, rather than cultivating the crop, Jesuit missionaries relied on indigenous people to collect wild cacao pods in the Amazon region.

After a few decades, she said, enslaved Africans became the backbone of the cacao economy, in particular in Brazil and Venezuela, connecting cacao with the larger network of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Portuguese slave traders exchanged cacao for enslaved Africans in Caracas, and exchanged part of the beans for silver in Veracruz. From there, remaining cacao beans were shipped to Spain and other important European centers.

Juarez-Dappe said the adoption of technological innovations in chocolate manufacturing during the late 18th and 19th centuries mark the “second-most important revolution” in chocolate. Modern production methods improved the quality of the finished product and resulted in diversification and mass production, making chocolate more accessible to the general population.

“The technological revolution increased the supply of chocolate and made it more affordable, leading to the development of a true mass market for chocolate,” she said. “Companies such as Cadbury in England and Hershey in the United States helped steer consumers into certain directions as chocolate was defined as an affordable and nutritious product that helped children, women, men and the elderly. They would eventually associate it with ‘womanly virtues’ and eventually, romance.”

Juarez-Dappe said the 21st century is opening a new chocolate era in which the barrier between consumer and producer is disappearing and sincere efforts are being made to create more social, just and equitable chocolate industry. Photo by Geshas, iStock.

The increase in chocolate consumption put pressure on chocolate manufacturers to find new areas cacao production. Cacao trees can only grow within the latitudes of 20 degrees north and 20 degrees south, limiting where growers could establish plantations. Cacao soon became an important crop in San Tome, Ghana, the Ivory Coast and Nigeria.

“To force the African population to participate in cacao production, colonial powers developed a large number of coercive mechanisms that included indentured servitude, forced taxation systems and outright human trafficking,” Juarez-Dappe said. “Because the production of chocolate was separate from the cacao production, the manufacturers claimed they didn’t know what was happening.”

That wall of separation began to crack in 1906, when a reporter wrote about the oppressive scheme called “servicais” — that all but in name resembled slavery. Developed by the Portuguese authorities, the system provided labor on cacao plantations that supplied Cadbury, whose owners at the time proudly touted their anti-slavery Quaker faith as influencing their business practices.

“As you can imagine, the story caused quite a scandal at the time, forcing Cadbury to proclaim it would do all it could to ensure the workers of its suppliers were treated fairly,” she said.

How much that pledge meant is up for debate, said Juarez-Dappe, pointing to a 2010 documentary, “The Dark Side of Chocolate,” that exposed modern-day child labor and human trafficking on cacao plantations in the Ivory Coast.

But she noted, “the 21st century is opening a new chocolate era in which the barrier between consumer and producer is disappearing.”

“Fair-trade practices and sustainability are connecting consumers with producers — particularly small artisanal producers — in a more direct way, creating a bridge between both groups,” she said. “This is leading to a more social, just and equitable industry in which the chocolate maker actually knows where the cacao comes from, who the people are who are growing and harvesting it, and can assure that people are being treated fairly every step of the way.

“There is still a lot of work to be done, but progress is being made,” she added.

experience

experience