CSUN Prof’s Book on Blacks’ Portrayal in Comics Nominated for Eisner Award

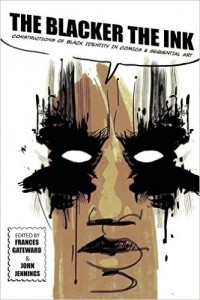

“The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics and Sequential Art,” an anthology that explores black identity on the comic pages and in comic books and graphic novel, and co-edited by California State University, Northridge professor Frances Gateward, has been nominated for a Will Eisner Comic Industry Award.

“The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics and Sequential Art,” an anthology that explores black identity on the comic pages and in comic books and graphic novel, and co-edited by California State University, Northridge professor Frances Gateward, has been nominated for a Will Eisner Comic Industry Award.

Named for acclaimed comics creator Will Eisner, the awards, sometimes called “the Oscars of comics,” are given by Comic-Con International to highlight the best publications and creators in comics and graphic novels. “The Blacker the Ink” has been nominated for an Eisner in the category of best academic or scholarly work.

Gateward, an associate professor in CSUN’s Department of Cinema and Television Arts who heads the media theory and criticism option, said the nomination was unexpected, but welcomed.

“I have geek credit now,” she said, laughing. “[The nomination] feels fantastic. What really excites me is that most of the publications I write for tend to be academic. I am a cultural critic, and I’d like to think I have a wider audience than that. This nomination means that people outside of academia have seen my work, and that’s a great validation.”

Gateward co-edited “The Blacker the Ink” with John Jennings. The duo earlier this year received the Ray and Pat Browne Award for Best Edited Collection in Popular Culture and American Culture, from the Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association.

The 15 essays in the book, written by academics, explore a gamut of sequential art — from the early days of newspaper comic pages to graphic novels — with subjects such as race and science fiction, gender construction, colonialism and African-American history.

Gateward said comics have always been part of popular culture, serving as a way to illustrate or comment on contemporary society. How people are portrayed, however, depends on who controls the publication.

The emergence of African-American newspapers in the early 20th century, she said, offered an alternative portrayal of African-American life to those found in the stereotype-riddled images of more mainstream publications.

“The people in power wanted to define what blackness was, rather than let black people define themselves,” she said.

As African-American artists began to publish independently — and to find jobs at Marvel and DC Comics — they began to tell their own stories in the comic pages and graphic novels.

“Stories of who we are and what we are capable of began to change,” Gateward said.

Today, there can be a black-Latino Spiderman, and people, regardless of race, are reading the story, she said.

experience

experience