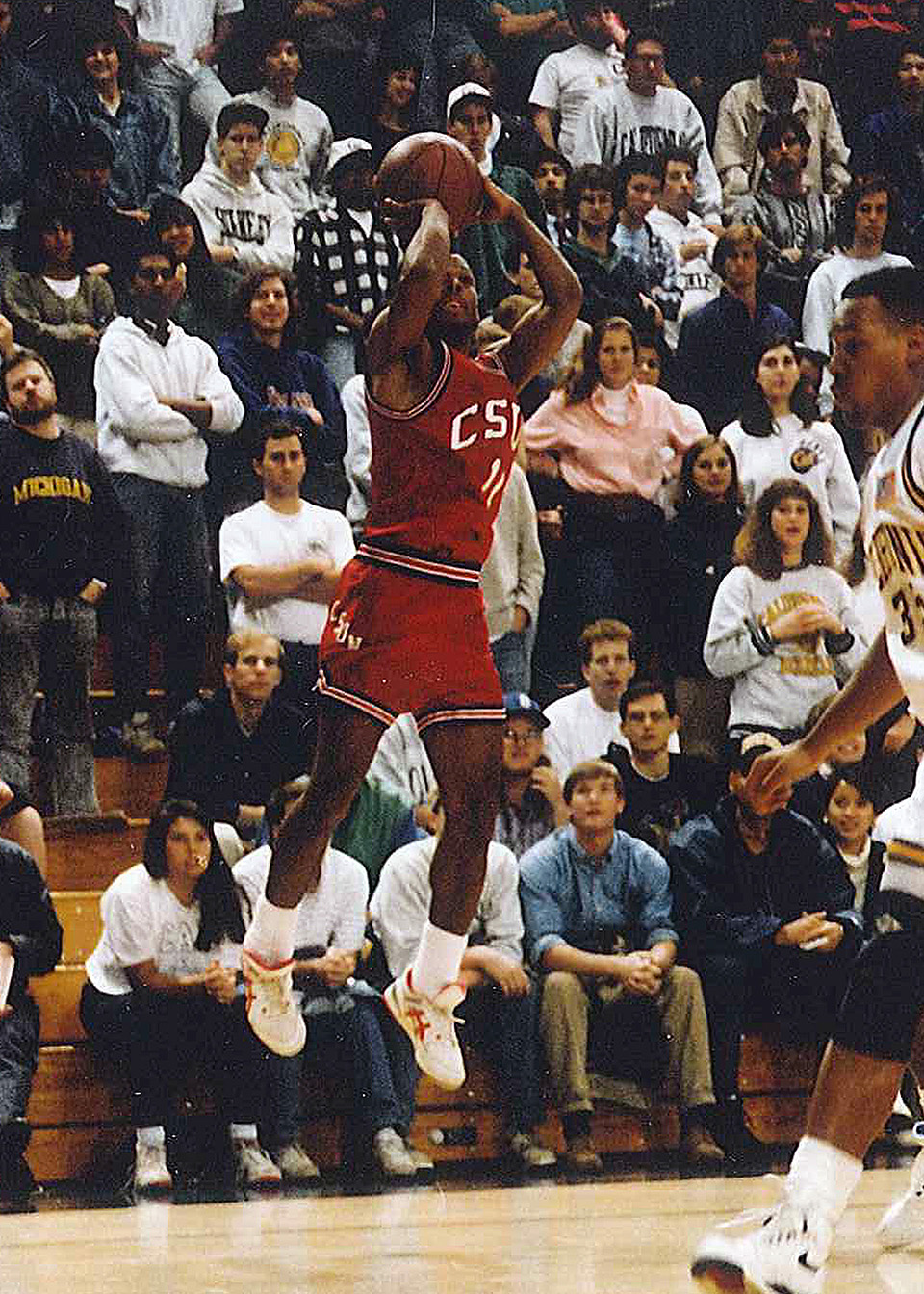

The Willpower of Hall of Famer Andre Chevalier

Sometimes he’ll try to get a laugh out of it.

He’ll explain that a car fell on his hand or a reptile ate two of his fingers.

Andre Chevalier ’94 (Afro-American Studies), M.A. ’07 (Secondary Education) knows that people often stare at his left hand, so he had to come up with something more interesting than the simple fact that he was born with three fingers.

He’s also partially blind in his right eye. When he was a child, his family dog developed an illness that he said somehow got passed to him through his eye. It destroyed the retina, so the only sight he has in his right eye is peripheral.

One can imagine that a basketball player, quick as thunder, with great shooting and passing ability, still might get passed over by university after university based on these two disabilities.

However, CSUN didn’t pass. And for that, the university and Chevalier are greater.

Chevalier will be inducted into the Matador Hall of Fame on July 24.

Chevalier, owner of a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from CSUN — the first person in his family to go to college — ranks in CSUN’s all-time Top 10 in 15 statistical categories.

As of the start of the 2015-16 season, Chevalier had scored the seventh-most points (1,311), played the sixth-most minutes (3,267), dished out the second-most assists (481), connected on the third-most free throws (396) in the fifth-most free-throw attempts (486) and recorded the third-most steals (184) in program history. Chevalier also ranked fifth in career free-throw percentage (.815).

He tallied up all of these feats in spite of the challenges he faced.

“I was born with a disability on my hand, and being a point guard — especially striving to be [an NCAA] Division I point guard — a lot of coaches would look and say, ‘How can I recruit you as a point guard when you have basically half a hand?’” Chevalier said. “I definitely had to endure that and work probably 10 times as hard as other people to make sure that it wasn’t a deficiency that showed up in games.”

Chevalier spent the first 12 years of his life in Landover, Maryland — where he said most people in his community struggled to graduate from high school, and there was no thought of college.

His mother, Shirley, moved the family to North Hollywood, California so she could better herself. Chevalier said the move ended up benefiting him.

He became a basketball star at Cleveland High School in Reseda and stayed local by going to CSUN.

During his four years on the court for the Matadors, he usually sank his shot. if he got anywhere near the free-throw line.

Because of the partial blindness, Chevalier’s peripheral vision was so good that he could see passing lanes in the corners better. Hence, he is known as one of the best assist men in CSUN history.

He admitted that having three fingers on his left hand was a weakness early on, but it made him work harder to dribble better. When there was no pressure, he’d bring the ball up the court dribbling solely with his left hand. If a defender came up quickly, he could cross him over by going to his strong side, the right side, with ease. Combined with his quickness, that gave Chevalier space to shoot or an easier path to the basket.

In the final game of Chevalier’s career, he scored 38 points — a single-game CSUN record for the team’s NCAA Division I years and one point short of the school record of 39. It came in a 95-87 victory over San Diego State on March 3, 1994. With the points, he also became the school’s all-time leading scorer — a mark since passed by six players.

Chevalier worked briefly in banking and the music industry after graduating, but he quickly changed careers. The varsity head coaching job opened up at his alma mater Cleveland, and he was pushed to interview. Chevalier said he only wanted the experience of the interview. Instead, he got the job at just 24 years old.

For the past 20 years, coaching has been his life, as well as education.

He has held coaching and administrative positions at Cleveland and Oaks Christian School in Westlake Village (where he guided the team to a California Scholastic Federation Southern Section division title) and Sierra Canyon School in Chatsworth. He also was an assistant coach at CSUN. He’s currently an associate director of admissions at Sierra Canyon.

But Chevalier has a lofty goal that doesn’t involve basketball.

He is working on opening his own charter school at a to-be-determined site in 2020. It would be an all-boys school, starting with high school classes. Chevalier said he aims to expand the school eventually to K-12.

“Although I love basketball, education is the thing I think will help my community most,” Chevalier said.

He said he wants to inspire others — and he already has.

When he was growing up, kids picked on Chevalier because of his hand. He used to hide it — in his pocket, in his shirt, wherever he could. He said he didn’t start to feel comfortable in his own skin until he was in his 30s.

At CSUN, Chevalier became one of the most visible, well-known players in Matadors basketball history.

“Because of my hand, I was probably super introverted because I didn’t want anyone to see my hand,” Chevalier said. “Here [at CSUN], I learned it was OK to be seen.”

experience

experience