Learning Lessons from the Incarceration of Japanese Americans to Improve Lives of Asian Americans Today

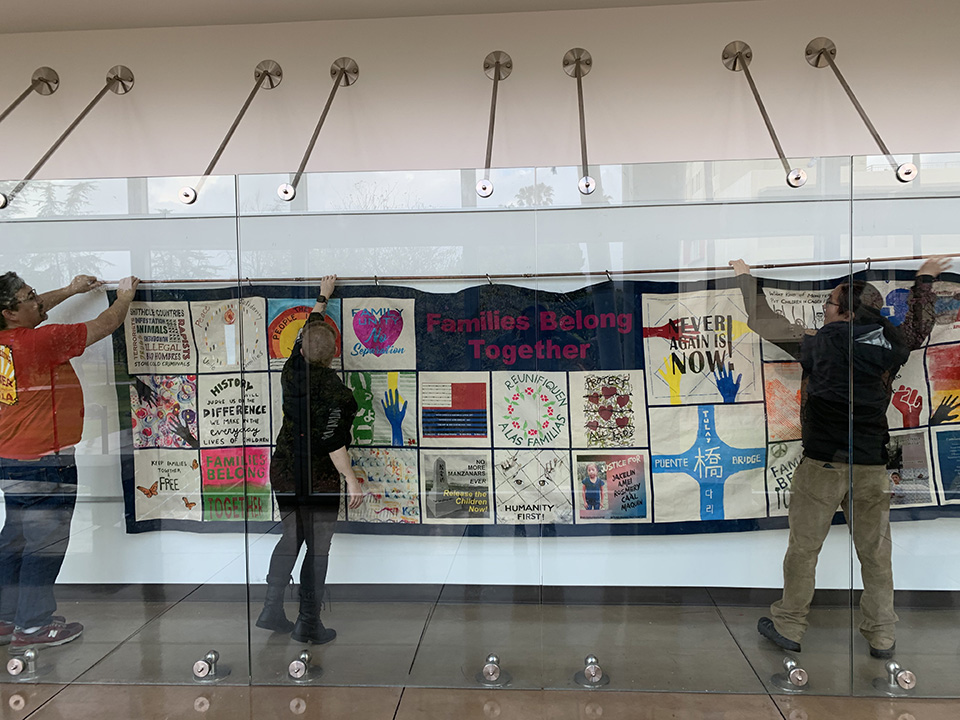

A “Tsuru for Solidarity” quilt being put up earlier this year in Manzanita Hall by CSUN alumnus and member of Tsuru for Solidarity member Tony Osumi (left), CSUN student Elayna Bisby (center) and Asian American studies professor Clement Lai (right). Lai is a faculty member with CSUN’s Civil Discourse and Social Change, which has received a $100,000 grant from the California Civil Liberties Public Education Fund to draw on lessons learned from the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II to improve the lives of Asian Americans today. Photo courtesy of Jinah Kim.

Faculty at California State University, Northridge are hoping to draw on the experiences of Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II to initiate discussions about and action around the continuing struggles for social justice among Asian American and Pacific Islanders living in Southern California, and particularly the San Fernando Valley.

The California Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, a project of the California State Library, has awarded CSUN’s Civil Discourse and Social Change a $100,000 grant to support a year-long project, “World Remaking: Intergenerational Activism and Transformative Justice,” The project will use lectures, storytelling and performance to build bridges between generations and communities to explore ways to address issues of incarceration, deportation, detention and criminalization for some of the most underrepresented Asian/Pacific Islander groups in Los Angeles, including Pacific Islanders, Muslims, Southeast Asians and Japanese Americans.

“The idea for the project came from a rise in the intergenerational and interethnic solidarity among Asian American and Pacific Islander, Latino, African American and indigenous communities, when addressing issues of incarceration and deportation,” said Jinah Kim, an associate professor of communication studies. “Many Californians know the history of Japanese American incarceration in concentration camps during World War II, but they do not know that these unjust laws continue to influence the treatment of Asian Americans and other racialized communities today.”

Members of the Civil Discourse and Social Change team, from left, Jinah Kim, Vivian Le Ly, Jason Quan, Clement Lai and Manija Said. Photo courtesy of Jinah Kim.

Kim is working with Clement Lai, an associate professor of Asian American studies, on the project. One of their goals is to educate people across generations and ethnic communities about the discrimination and marginalization experienced by Asians in America.

“It’s staggering to think about how many Japanese Americans have never heard about their parents’ experience in the concentration camps,” Kim said. “Similarly, many undocumented Latino Dreamers talk about the pressure they feel to be silent about their parents’ status to seem more American.”

That pressure to be silent is traumatic, Lai said.

Lai said the World Remaking project “draws inspiration from the past and ongoing activism of Japanese American survivors of the WWII incarceration and their descendants that spans across multiple generations and organizes with different racialized communities, as seen in the activist coalition Tsuru for Solidarity’s organizing against family separation and the detention of migrant children at the border with representatives from Latinx, Muslim American, African American and Native American organizations.”

“This is the generation of activists and artists that inspired Jinah and myself to become organizers and/or professors,” he said. “The activism and artivism of this community forms one of the key foci of our project. But we also want to create events that organize in solidarity with or that bring different communities together across generations and racial lines, like Tsuru, to learn, share, create, make community and organize around social justice issues that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are facing now with regard to deportation, gentrification, global warming, colonialism — in short, systemic vulnerability.”

“We hope to create a space where young people can learn from older people,” Kim said, “and I think older people will learn from the younger ones, as well.”

Student Jason Quan folding an origami crane, a “Tsuru,” during a “Tsuru for Solidarity” event hosted by Civil Discourse and Social Change. Photo courtesy of Jinah Kim.

World Remaking is organized as a series of public talks, arts workshops, storytelling circles, performances and screenings on intergenerational activism, transformative justice on incarceration, interethnic solidarity and the work of preserving memory in danger of disappearing.

While Kim and Lai are still figuring out the logistics of the series in light of social-distancing imposed on public gatherings as the result of the COVID-19 pandemic, they expect to host the first World Remaking event in the early fall. The topic will explore the similarities between the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and the detention of migrant children at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2019.

Other events in the series include a storytelling circle featuring representatives from a variety of community-based organizations; a lecture and zine-making workshop focused around stories of migration; a performance and workshop that highlights the danger of racial hysteria during wartime and the need for interracial solidarity; a social justice student research conference centered on the theme of incarceration, deportation and transformative justice; and a strategy session for action and implementation of transformative justice tenets.

Details about the World Remaking project can be found on Civil Discourse and Social Change’s website.

The California Civil Liberties Public Education Fund supports public education projects focused on the causes of the exclusion, removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Since 2017, the program’s efforts have expanded to include a focus on public education projects that examine civil right violations and civil liberty injustices due to race, national origin, religion, gender, sexual orientation and immigration status.

CSUN’s Civil Discourse and Social Change is a campus-wide initiative that combines education, community involvement and sustained activism on issues around social justice and social change. Civil rights icon the Rev. James L. Lawson Jr. serves as an advisor to the program.

experience

experience