Robot May Help CSUN Marine Biologist Find Clues to Protect Vanishing Corals

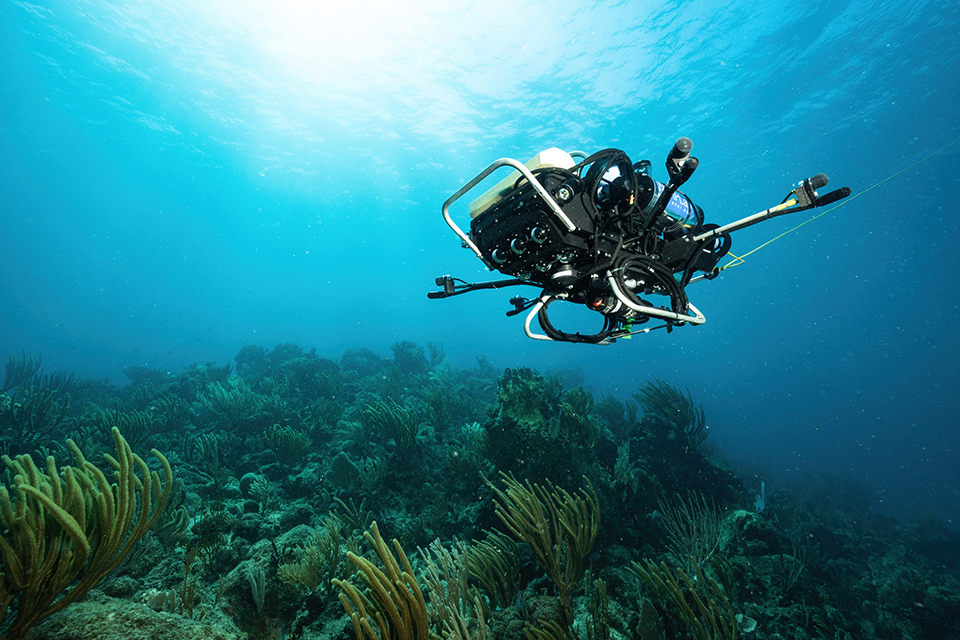

This intrepid underwater robot may help CSUN marine biologist Peter Edmunds find clues for protecting vanishing coral species in the reefs of the U.S. Virgin Islands. Photo by Austin Greene, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

CUREE is about three-feet long and kind of looks like a complicated, convoluted video camera. This intrepid underwater robot may help California State University, Northridge marine biologist Peter Edmunds find clues for protecting vanishing coral species in the reefs of the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Edmunds and Yogesh A. Girdhar, a computer scientist with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Massachusetts, the world’s largest independent marine research facility, have received a combined $300,000 in EAGER (EArly-concept Grants for Exploratory Research) funds from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to explore the use of an AI-powered robot—WHOI’s Curious Underwater Robot for Ecosystem Exploration (CUREE)—to survey coral reefs and find rare coral species whose number have declined to the point that it is nearly impossible for human divers to locate them.

“The state of the coral reefs in the Virgin Islands is a bit grim,” said Edmunds, who teaches in CSUN’s College of Science and Mathematics. “Some of those corals are so uncommon they are falling through the cracks of our ability to find them because humans can’t physically spend enough time underwater to search large areas of reef. This is where the robot comes in.

“We’ve been dreaming of the time where the robot can be operated by engineers and overseen by ecologists,” he said “The robot will be able to go up and down the reef. Maybe it finds the last two colonies of a coral species you are interested in and then returns to you and says, ‘This where they are. Here are the GPS coordinates. Here are pictures of them. Tell me what else you want to know.’”

Edmunds said that information the robot gathers is important “because we are talking about the possible extinction of a species.”

“It can help determine what we do, or not do, to protect the species,” he said. “I think it’s very dangerous to claim the sky is falling when it is not. When we’re talking about rare corals or rare marine organisms and thinking about taking some sort of draconian measure like pulling them off the reef and keeping them alive in an aquarium, we want to make sure that we are making the right decision.

“Are they truly rare, truly on the verge of extinction? Or are they just uncommon. Their populations sizes have declined, but they are still there and still an integral part of the marine ecosystem,” Edmunds said. “We must be careful because our actions as potential saviors of rare corals have consequences.”

The project is a natural next step in Edmunds’ nearly four-decade-long effort to chronicle life on the coral reefs off the Caribbean Island of St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. For 37 years, he has taken photographs and made detailed notes on the marine ecology off St. John. He will be tapping into that knowledge and his intimate familiarity with the coral species that live on the reefs to help Girdhar develop a program to train CUREE to identify rare and vulnerable coral species.

“This has never been done before,” Edmunds said. “We don’t know whether the robot can be trained to find these corals.”

He and Girdhar are hoping to capitalize on artificial intelligence’s ability to learn by analyzing and classifying large numbers of images, and to make decisions based on the trends it finds in a large data set. This is similar to the facial-recognition systems used by the Department of Homeland Security to identify protentional terrorists in a crowded airport. But, in this instance, they are hoping to teach the robot’s artificial intelligence the nuanced differences between “the little wiggles of one coral skeleton and the wiggles of another coral species,” Edmunds said.

“If we are successful, CUREE will not only learn that certain shapes correspond to different coral species,” said Girdhar. “It will also be able to detect the right habitat types to adaptively focus its efforts to find coral of a particular species.”

Because the coral species they are looking for are so rare, Edmunds explained, it can take researchers hours of underwater searching before they find them. The researchers then face dozens of additional hours underwater taking a census of what they see.

“The human body cannot stay underwater for the six, nine, or 12 hours it might take to find a tiny rare or uncommon coral species. Spending that much time underwater creates serious health consequences,” he said. “But a robot can do it.”

The willingness to test the unknown led to the EAGER grants, Edmunds said.

“The grants are designed to encourage scientists to take risks and try something new,” he said. “Which is definitely what we are doing. If we succeed, what we’re doing could have implications for all of biological research.”

The grant also provides an opportunity for CSUN students—many of whom are first-generation and from underrepresented communities—to work on a project that could have applications for marine biological research around the world. Edmunds is also thinking of involving students at local high schools.

“I think it would be awesome to bring our CSUN students and Yogi (Girdhar) to the local high schools and show them how we’re using a robot to do biological research,” Edmunds said. “I think it would stoke an excitement about possibilities for research that we haven’t even thought of yet.”

experience

experience