Climate Change and National Parks: A CSUN Grad’s Unique Perspective

Heat, drought, fire and extreme weather have dominated the news of late. July 2023 was the hottest month on record. The historic Hawaiian capital of Lahaina, on the island of Maui, was destroyed by wildfires earlier this month, driven by tinder-dry conditions and hurricane-force winds from Hurricane Dora.

“We don’t use the term ‘fire season’ anymore. It’s become a ‘fire year,'” said Mike Theune ’11 (Recreation and Tourism Management), who works for the National Park Service. “In August, we definitely do hit the peak of the fire year — especially in places like California — but the potential for wildfire is year-round.”

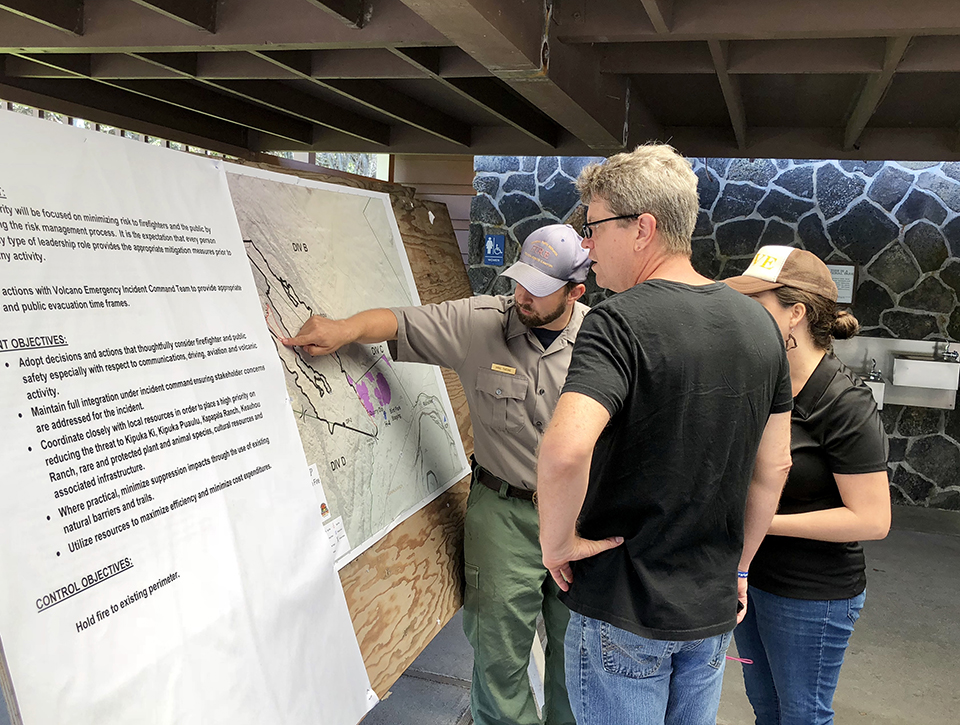

Theune is the regional fire communications and education specialist for the National Park Service Pacific West Regional Office. He is one of nine who are located throughout the United States, dispatched during emergencies to keep the public informed about fire and safety conditions. The job, he said, ranges from scheduling public meetings to directing communications during dramatic evacuations.

“I’ve been evacuated or put on evacuation notice in every place I’ve ever lived. I’ve worked during hurricanes. I worked [during] a volcanic eruption.”

With drought conditions and extended periods of hotter weather, Theune says he expects more travelling this year.

“Last year I was gone about 170 days from home on fires and other incidents. This year, it’s probably going to exceed that — probably closer to 200 days supporting national parks,” he said.

In all, Theune has worked 15 years for the park service. He shared his unique perspective on climate change with CSUN Today, and how it has affected the parks and changed his approach to his job.

Fire Danger in Unlikely Places

At the time of this interview, Theune was in Olympic National Park in Port Angeles, Wash., monitoring high fire danger.

“The Olympic National Park is an absolutely beautiful, amazing park. But they’re in a drought and it’s a rainforest,” Theune said.

The Hoh Rainforest, within the park, experiences a yearly average precipitation of around 140 inches. The area is now considered “abnormally dry” according to drought-monitoring agencies.

“There was a fire called the Paradise Fire in 2015 — not to be confused with the Paradise fire in California. That was one of those indicator fires for me, that climate change is really affecting our national parks. When you have a wildfire in a rainforest, how do you wrap your head around that?”

Changing Tactics

Theune noted that the changing climate has forced changes in fire management. For periods of time throughout the 20th century, suppressing all fires was the practice during forest fires. But some fires, like those started by lightning strikes, are part of the ecosystem— a natural process that cleared overgrowth and improved the health and balance of a forest. With suppression, that growth remained and created competition for water, thus making drier conditions and an abundance of wildfire fuel. Theune said “prescribed burns,” formerly referred to as “controlled burns” have been re-introduced in the parks.

“We look at the forest and based on the vegetation and fuel type, the slope, the topography, the conditions, temperature [and] weather — based on those factors, we come up with a prescription [for where and when to burn],” Theune said.

“What we’ve seen is, in places that have had prescribed burning, they’re actually more resilient to catastrophic large-scale wildfires,” he said. “A good example was in 2021, the KNP Complex fire in Sequoia National Park. We saw the fire stop where we had recent prescribed burns. Having recent fire history reduces the fuel loading and thus reduces the intensity of the wildfire; ultimately making it easier and safer for us to build containment lines.”

Keeping Informed: Social Media and the Internet

Theune advises the public to visit .gov websites for safety information. Those sites are particularly important for tourists, who should make an emergency plan prior to visiting a park.

“That makes our jobs as fire managers easier, [when] you know people have a plan,” he said.

For more information about the national parks, visit nps.gov. For more information about CSUN’s Department of Recreation and Tourism Management, visit their webpage through the College of Health and Human Development.

experience

experience