CSUN Biology, Kinesiology Profs Show Benefits of Exercise Through Rat Studies

Hidden behind imposing laboratory doors, a militia of rats are lifting weights on miniaturized bench presses and running on mini treadmills. Scientists are scribbling notes and analyzing the rats’ tissue samples.

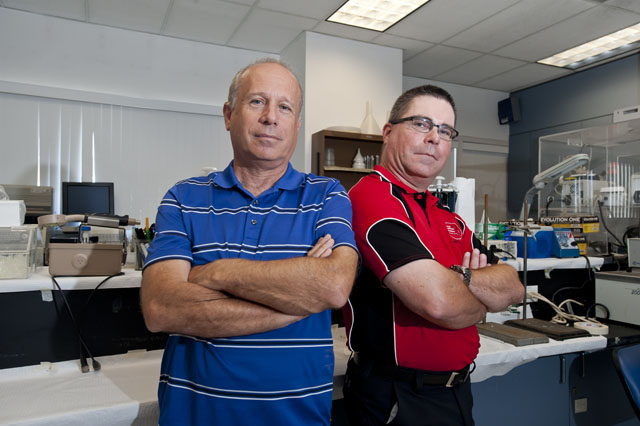

This is the scientific frontier for two California State University, Northridge professors who are one step closer to understanding the benefits of exercise for humans. Kinesiology professor Ben Yaspelkis and biology professor Randy Cohen have been examining how exercise affects two different areas when it comes to the health of mammals as a whole — including humans.

Yaspelkis’ rat study, which has been ongoing for more than 15 years, focuses on the impact of exercise on insulin resistance, also known as diabetes development and determent.

“We’ve been interested in trying to understand a Type 2 diabetic [rat] model,” Yaspelkis said. “We are looking at a high fat-fed rat, which is an environmental model.”

An environmental model focuses on the lifestyle “choices” of the rat or other mammals — which for humans translates to food consumption and sedentary versus active habits, he said.

“We are looking at an environmental model, since most humans develop insulin resistance for the most part because of the environment they are in,” Yaspelkis said. “It’s what they’re eating, and couple that with a lack of physical activity — it causes insulin to have less of an effect.”

Cohen, who has been researching biology for more than 25 years, is studying the neurological effects of exercise in rats with ataxia, to understand how it could benefit human ataxic patients.

“Ataxia is the destruction of brain or spinal cord cells in the back of the brain, in the cerebellum,” Cohen said. “It causes an inability to walk. By the time these animals hit adulthood, they have the inability to move their hind legs. They can’t move, just like human patients with ataxia.”

While the two professors are not working on their current research together as they have with past papers co-authored, their rodent studies — which share some similarities — yield revealing results for humans as they consider the benefits of exercise.

In Cohen’s rat model, he placed the animals on treadmills for 30 minutes, five times a week and monitored the growth of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which protect Purkinje cells. Purkinje cells are responsible for proper motor function in the cerebellum.

“In synaptic connections and in adult mammals, BDNF seems to promote neural protection,” Cohen said. “We showed that acute exercise leads to a doubling of BDNF levels in the brain. It greatly prolonged [the rats’ lives] by about 20 percent.”

What shocked Cohen, however, was that if a rat was fed a high-fat diet and still exercised, the BDNF levels did not change in ataxic patients, leaving the Purkinje cells to further deteriorate in the brain.

“Fat negates exercise,” Cohen said, slamming his hand on his desk. “I just find it amazing. It was against my basic instinct, which is a high-fat diet is needed to survive — and these animals are going to gain more weight and survive longer. But, high-fat diet in this experimental paradigm leads to a decrease of life.”

Yaspelkis discovered in his study that no matter what exercise the rats performed — be it lifting weights or running on a treadmill — both were equally effective in improving insulin function in the rats.

“Our initial hypothesis was that aerobic exercise would have a greater effect,” he said. “At the end of the day, as long as the muscle is recruited and active in something, we are going to get an improvement in how insulin will do the job it’s supposed to do.”

When Yaspelkis’ diabetic rats were put on a high-fat diet, the result was in stark contrast to Cohen’s rats’, which showed there was no change in the ataxic rats if they ate a high-fat diet and exercised.

“When we took the animals off the high-fat diet, it was concurrent to the control,” Yaspelkis said. “Exercise was so powerful that it essentially reversed the effect of the high-fat diet.”

Cohen highlighted the benefits of exercise in an article he released with CSUN biology graduate student Brooke Van Kummer in 2014.

“Exercise has been shown to be an inexpensive and practical treatment for a myriad of neuromotor disorders,” the article noted.

Yaspelkis said he has marveled at the tremendous benefits that exercise provided in these studies.

“It is remarkable,” he said. “The only single change you are making in these animals is asking them to be active. I think that is a huge crossover when you look at the human population. Exercise is medicine.”

experience

experience