CSUN Satellite to Explore the Stellar Frontier

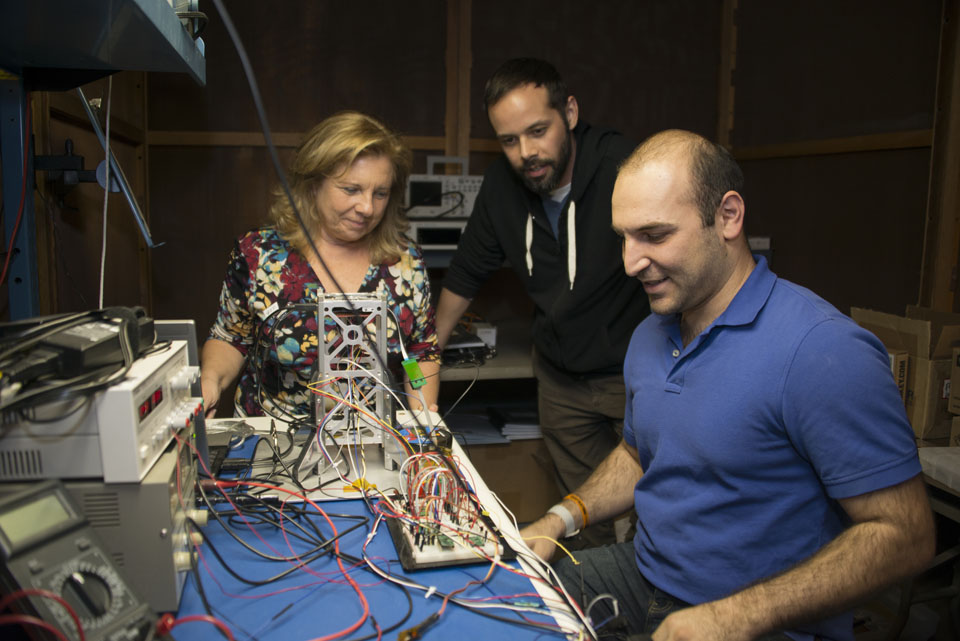

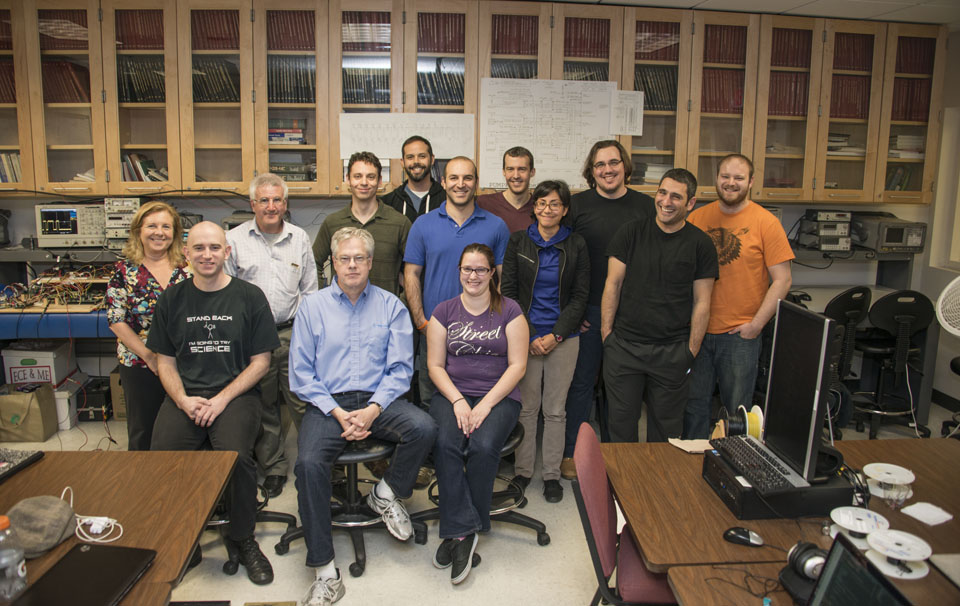

In a small, multipurpose electrical engineering lab located at the heart of campus, a team of 27 California State University, Northridge students, four professors and a Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) scientist eagerly gathered around a table covered with circuit boards. They were witnessing a historic first rehearsal between the custom-made CSUNSat1 cube satellite and a JPL energy storage system that will help explore deep space in extremely cold temperatures.

The project is led by CSUN electrical and computer engineering professors Sharlene Katz and James Flynn, in partnership with JPL. The CSUNSat1 CubeSat — a miniature satellite that will ride on board a rocket also launching a larger satellite — could be launched as soon as next year to test the effectiveness of JPL’s energy storage system.

“CubeSats are like hitchhikers,” Katz explained. “In a sense, the ride is free if you are selected [for the expedition].”

Standing at 10 centimeters deep, 10 centimeters wide and 20 centimeters tall, CSUNSat1 will house custom-made circuit boards created by the CSUN students; JPL’s storage system; a unique, infrared ‘flashlight’ to shine waste energy into space to keep the satellite cold and a nameplate with the names of the CSUNSat1 team. The home base for CubeSat communications will be at CSUN.

After applying for a “ride” on a larger satellite, CSUN was one of 14 universities selected out of more than 100 applicants for the orbital journey, by the NASA Cube Sat Launch Initiative. Prior to being picked, Katz and Flynn received a $200,000 grant from NASA to fund the project.

“We don’t have a lot of money or space to work with,” Katz said. “This room we are in is a laboratory that classes are taught in. We don’t really have a lab that is exclusively for the cube sat development. Fortunately, not many classes are taught in here. It’s one of the biggest challenges. We have to put everything in a screen room and lock it up each night with a padlock.”

The most challenging aspect of the project, for the students, was creating a method of switching power from the main source in the cube satellite to the energy storage system, Katz and Flynn noted.

“We have to be able to change power supplies mid-mission,” Flynn said. “That’s like driving on the 405 and changing engines in the middle of your commute.”

JPL scientist Gary Bolotin said he plans to conduct multiple launch rehearsals with the CSUNSat1 team. For the project to be a true success, he said, practice makes perfect.

“This is a lot of fun! I’ve been pushing for many rehearsals before the launch,” Bolotin said. “It’s also scary. One of JPL’s CubeSats was destroyed when the Russian rocket carrying it blew up. JPL’s secret to success is to test, test, test and test until the execution is flawless.”

Computer science and mathematics major Jonathan Castello said he is ecstatic to get an opportunity to work on CSUNSat1.

“I got interviewed to be a part of the CubeSat team last summer,” he said. “I’ve heard about hard-level software, but I never had the opportunity to put it into practice before. The CubeSat drives it home with how interconnected software and hardware really are.”

Flynn explained that the project provides CSUN students an advantage when entering the computer engineering job market.

“This [project] is something JPL does with its first-year hires. And these guys and girls aren’t even out of [college], and they are working on a satellite,” he said.

Bolotin usually works on Mars expeditions, such as the upcoming Mars 2020 mission, but the CSUNSat1 project is important because it gives undergraduate students an opportunity to work on a real space mission, the scientist said.

“We’re really jazzed about it,” Bolotin said. “I love it. These are our future engineers for the country.”

experience

experience