CSUN Alum Uncovers Early Homestead Owned by African American Woman in Santa Monica Mountains

John Ballard Homestead with two women out front, presumably Alice Ballard and Francis Brigs Ballard, Alice’s step-mother and John’s second wife, date unknown. Photo courtesy of Austin Ringelstein.

In 1900, just four years after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation in the Plessy v. Ferguson case — and decades before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — Alice Ballard, an African American woman and daughter of formerly enslaved people, owned 160 acres in the Santa Monica Mountains.

Little has been known about this groundbreaking woman and her life, but CSUN alumnus Austin Ringelstein ’16 (M.A., Public Archaeology), with the help of James Snead, a professor of anthropology, and several current students in the CSUN Department of Anthropology, are working to tell her story.

CSUN students in the Department of Anthropology, surveying the site where Alice Ballard’s homestead was located. Photo courtesy of James Snead

“For a 30-year-old African American woman to receive 160 acres at the height of the Jim Crow period is remarkable,” Ringelstein said, referencing the Jim Crow laws, first enforced in the 1870s and requiring segregation based on race.

Not long after graduation, Ringelstein was hired by the National Park Service and asked to look into the history and heritage of African Americans in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, a job he was eager to take up. The objective of the project was to document the “African American struggle to gain equal rights as citizens” in the Santa Monica Mountains.

“[Projects like this] emerged from discussions that a lot of people have been having over the last five or six years, about African Americans living in the Santa Monica Mountains in the late 19th, early 20th century,” Snead said. “That’s not something that most Angelenos know about or at all. But they were there.”

Alice Ballard’s former homestead land. Photo by Austin Ringelstein

One of the mountains was recently renamed Ballard Mountain in honor of John Ballard, Alice’s father, very likely a formerly enslaved person from Kentucky who migrated to Los Angeles in the late 1850s, helped established the Los Angeles First African Methodist Episcopal Church (FAME), and made a series of real estate transactions in and around Los Angeles. Following a shift in demographics in L.A. as the population grew, and an economic depression in the 1870s, Ballard moved his family to a remote area of Agoura Hills, where he was the first African American to own a home in the mountains above the Malibu coastline.

Ringelstein loved John’s story, which had been researched by Patricia Colman, a history professor at Moorpark College. But he also wanted to shine the spotlight on John’s daughter — because so much history focuses on men, Ringelstein said.

He searched official government documents and newspaper accounts to paint a picture of Alice Ballard’s life.

Finding Alice Ballard

During his research, Ringelstein uncovered documents showing that in 1900, at the age of 30, Alice Ballard applied for a homestead — an area of public land, usually 160 acres, granted to a U.S. citizen, provided they had lived on the land for at least five years, “improved” it and built a home. In her Homestead testimony, Alice claimed to have lived on the land for 12 years and made $290 of improvements to it. Ringelstein isn’t entirely sure how she paid for her homestead, though he speculated she might have saved up doing work for a nearby family.

The 1900 census lists her as a “nurse,” and Ringelstein theorizes it is possible that she was a midwife to the few families living in that area of the mountains at the time. The government approved her application in 1901, just before her marriage to a Moroccan immigrant (and former enslaved person), Warner Bonettio — a wedding that even made the Los Angeles Times, due to Bonettio’s colorful groom’s apparel.

One of the bricks that were found on site. Made by the LA Pressed Brick Company, the manufacture of these types of bricks (1887 to 1926) overlap with the period of Alice Ballards occupation of the site (1889-1903). Photo courtesy of Austin Ringelstein

Not much else is known for certain about Ballard’s life. She was the youngest of seven children. Records indicated that her mother, also a former enslaved person, died when she was young, and it is probable that Alice took over much of the domestic work in her father’s house. She enjoyed working outdoors but was not a very good cook, according to a neighbor who wrote a book that included a chapter about John Ballard.

Before her homestead patent was approved, Alice was raising two children, named Lyman and George Ballard, though Ringelstein is uncertain about the identity of their father — they were listed as John’s grandsons on the 1900 census. When Ballard married Bonettio, the four of them likely lived on the homestead together, which was in an area of Agoura Hills then called Newberry Park.

They may have lived there until December 1903, when they sold the homestead for $10 dollars (approximately $300 dollars in 2019 value, adjusting for inflation). Ringelstein, aided by Colman’s research, theorizes that a large fire in early December 1903 that burned many homes and ranches in the Santa Monica Mountains may have also destroyed Alice Ballard’s cabin. Only days after the fire, she sold for the tiny amount of $10, suggesting that the fire probably influenced her decision to sell and that the fire may have devastated the family’s fortunes.

After moving from the Ballard homestead to the city, Ballard and Bonettio had three more children, Mary, Theodore and Fred. The 1930 census stated that Ballard, her daughter and only granddaughter lived together at the time and likely continued to live together until Ballard’s death in 1937. Ringelstein was able to locate Ballard’s granddaughter but hasn’t been able to get in contact with her.

Alice Ballard’s House Marks the Spot

A ceramic container fragment, date unknown, found on the site. Photo courtesy of Austin Ringelstein

After Ringelstein found hand-drawn maps of the area that showed the approximate location of Alice Ballard’s house in the Santa Monica Mountains, he began searching for it. Records show she had a one-room log house, and she cleared 10 to 15 acres of land, near a dirt road.

Even with portions of the road still existing, the rugged terrain made it a challenge to locate Ballard’s home site.

It wasn’t until the Woolsey fire burned the area in November 2018 that Ringelstein (along with fellow archaeologist Devlin Gandy) were able to visit and find artifacts from the approximate time period Ballard lived there, leading him to believe they’d found the site. Coordinating with some of the living descendants of the Ballard family — descendants of Alice Ballard’s brothers and sisters — Ringelstein teamed up with CSUN professor Snead to commission several CSUN archaeology undergraduates do a surface surveillance — meaning they only looked for items above ground and did not do any digging, to minimize their impact on the land.

There, they found broken bits of teacups, plates and even a bottle that once held Radium Radio, a local Los Angeles health drink circa 1905. This evidence led the team to conclude that the site contains materials from people who lived there or passed through the area before and after Alice Ballard.

It will take further archaeological testing and research to confirm whether any of the objects they found belonged to Ballard, Ringelstein said.

“One of the things about the students that really struck me is that they were particularly engaged in the idea that these are real people with names and histories, who [lived] here in the same community that we do, whose stories deserve to be told,” Snead said.

Rewriting History

Several of John Ballard’s descendants gathered on Ballard Mountain in 2018 for a Black History Month celebration. There, a plaque on Kanan Road was placed in his honor. Although the family’s historic significance has been celebrated in recent years, this was not always the case. People tried to burn down John Ballard’s home at least twice (once successfully), and before the mountain was renamed in his honor in 2010, it was known by a racial slur.

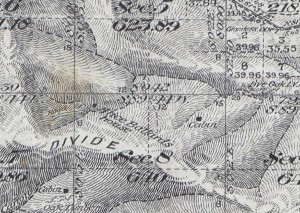

Close-up of 1898 US Surveyor General’s Office map showing the location of Alice Ballard’s house. Photo courtesy of Austin Ringelstein

“That mountain represents a man who considered himself an American when others called him something else,” Ballard’s great-great grandson, Ryan Ballard, said at the event, according to ABC7. “We can’t fix the past, but we can certainly do something today that celebrates who we are so that we will continue to forge ahead.”

As part of his work with the National Park Service, Ringelstein is currently working on a document dedicated to the history of African Americans in the Santa Monica Mountains area, with an entire chapter dedicated to Alice Ballard.

“There’s no real limit or set goal to this project,” Ringelstein said. “We hope that we honor the land and the legacy of the people that inhabited that space.”

This article does not represent the opinions of the National Park Service.

experience

experience