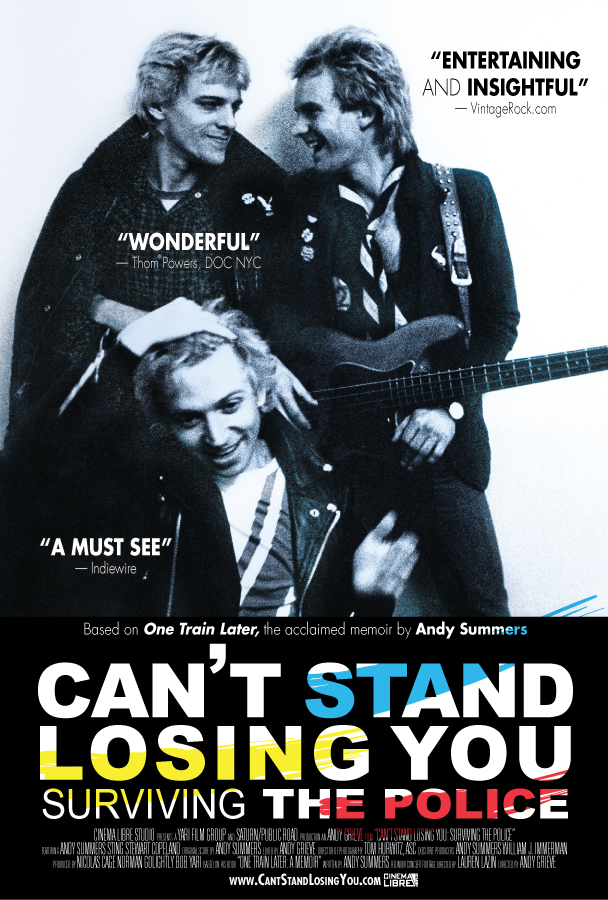

CSUN Alumnus Andy Summers Reflects on His Police Days and More in “Can’t Stand Losing You: Surviving the Police”

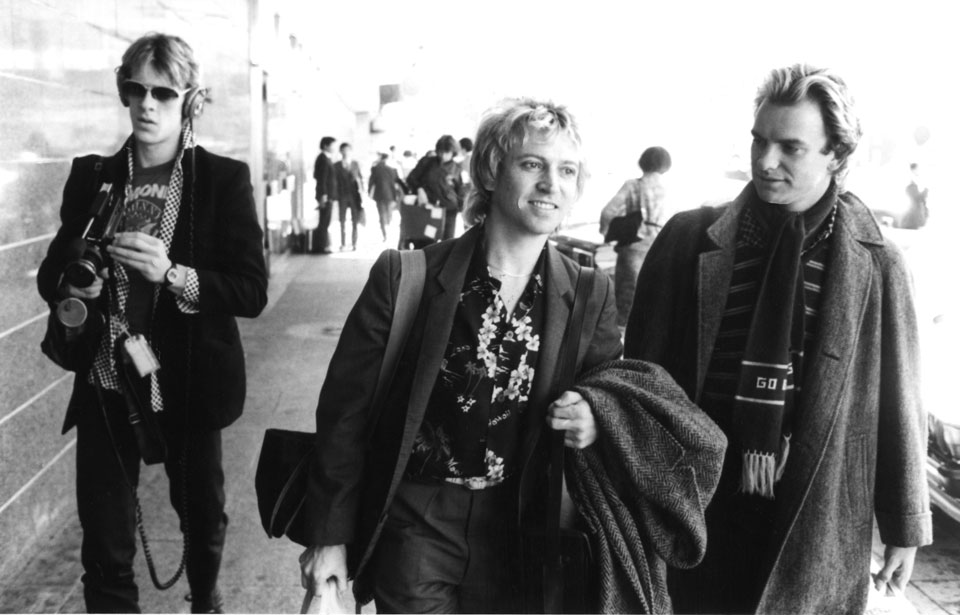

What would the history of rock ’n roll be without the Police? Band members Sting, Andy Summers ’72 (Music) and Stewart Copeland formed one of the transcendent bands of all time. Founded in the punk movement in London, the Police were actually miscast practitioners of that genre because of one important trait: they were all virtuoso musicians, Summers studying classical guitar at CSUN in the early 1970s. After the success of the classic “Roxanne,” the Police became regulars at the top of the charts and soon were in the rarefied air of hottest bands in the world. If not the hottest.

Yet superstardom did not come without a price. Creative conflict caused friction among the band members, and over time that slowly eroded what had been built starting out in small clubs in London and along the eastern seaboard in the U.S. At the apex of its popularity, riding the wave of the highly successful tour following the release of the classic album Synchronicity in 1983, the band would never record another album. By 1986 the band had broken up, though they would get back together in 2007 for a reunion tour that would become one of the highest grossing of all time.

Summers wrote the book One Train Later as a memoir to chronicle his earliest days playing the guitar in England, and eventually coming to the United States as a member of the Animals. The breakup of that band led to Summers attending CSUN, and it was that classical training he later applied to rock music and playing lead guitar with the Police. Summers used the memoir as a basis for the documentary Can’t Stand Losing You: Surviving the Police, which mixes archival footage on and off stage, as well as in the studio to give the audience a glimpse of what went into the rise and later fall of one of the biggest bands of all time. Spliced throughout the movie is concert footage from that 2007 reunion tour, which mixed well with the footage from the 1970s and ’80s. Summers gave some insight into the movie in this exclusive interview.

How did you approach this project?

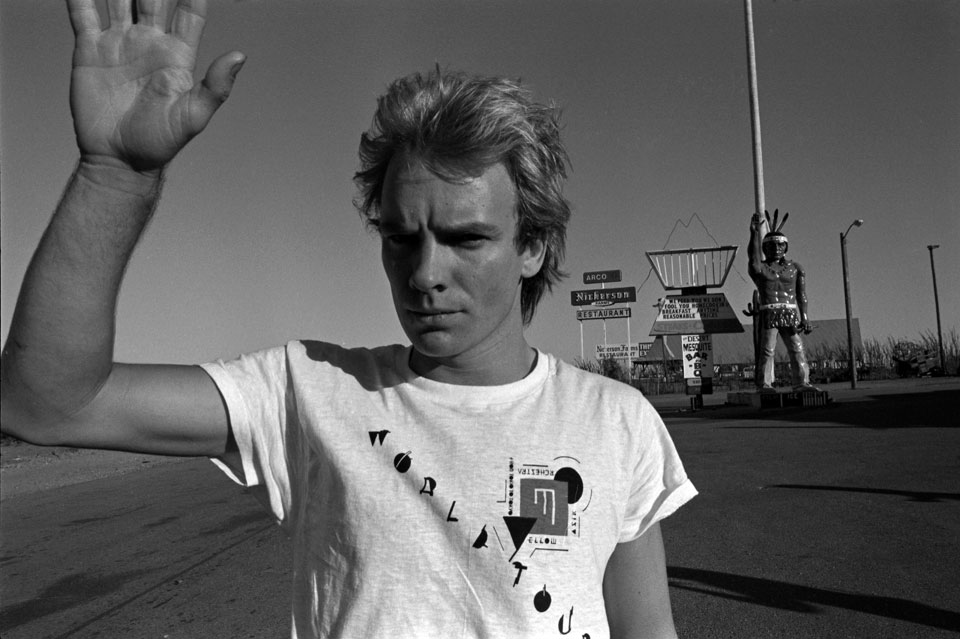

I was preparing a very big photo book from all the years of photography when I was in the Police. I still am actually. Around that time I saw a film called The Kid Stays in the Picture, which was a film produced by Robert Evans. What was interesting about that film was that it was made almost purely from still photographs, which were animated, and his voice-over. It occurred to me that I had the same material: the whole life story written out, a huge amount of photography and, of course, a preeminent band.

Just by chance I met somebody who was close friends with Brett Morgen, who made The Kid Stays in the Picture. She sort of mentioned ‘Why don’t you get in touch with Brett to see if he’d be interested in it?’ I subsequently did, thinking I was going to make The Kid Stays in the Picture Part II. I met with Brett, and we hit it off and I hooked him up with another producer friend of mine, Norman Golightly, who worked with Nick Cage for many years. The two of them got together with the plan in mind to convert the book into a movie. It was amazing. We sold it in two goes, basically.

I didn’t write the whole story thinking it was going to be a movie. That seems incredibly vain. I wanted to write, and it seems like a good place to start, and there was a message that I could put in the book for people who are interested in music.

Beyond the music, what makes the Police such an enduring band?

I really hope it is the music, because we’re not really around the public’s face at the moment. Although we never seem to really have left. I don’t want this to come out the wrong way, but I think it’s the personalities and the interactions and the actual chemistry of our trio that’s always connected with the audience. We had a lot of very sparky chemistry, as is really well known. It’s always fascinated the public, how we could get on stage and hammer out these great songs and have them connect. Certainly we proved that again on the reunion tour.

Many say your roots were as a punk rock band, but all three of you were accomplished musicians.

The punk thing in London was clearly a very exciting time, which pretty much overthrew the music industry in the U.K. at that time. If you weren’t punk you were out. So if you wanted to get a gig at all, you didn’t really have much chance to do anything unless you were a punk band. The Police, we started out as a so-called punk band, but it wasn’t what we really were. We were definitely a fake punk band (laughs). And we suffered for it. The critics and music press were onto us.

What saved us, of course, was coming to the U.S. and playing at CBGBs and rather than being punk we decided we were New Wave. But what happened ultimately we had “Roxanne” and we started to have these other songs. All that transcended these other categories that came and went. We were the Police. We were sort of in our own category.

Behind the scenes, with the sparky chemistry as you mentioned, how much was it the goal to show how you were able to still make these incredible songs?

We had this chemistry. For any rock band worth its salt you have to have that. You don’t really need mellow guys. Rock is inherently aggressive and in your face. That’s the kind of music it is. We were a guitar, bass and drums, and the bass player was the singer as well. You need that sort of very pushy attitude in it. It’s got to be musical, of course, and the music has to be dynamic. What you’ve got to do is psychologically find a way to work together and work it all out. The psychological knitting together again to be a trio and go out there, there’s only three of us on stage, and you’re really playing off the other two guys all the time. That’s what’s going on. So you can’t go out on stage in front of 50,000 people with absolutely ill will and think you’re going to pull it off. It has to melt away and you have to be in the moment in the music with the other players.

This movie balanced the musical brilliance with an honest portrayal of what led to the eventual breakup of the Police. How important was it to tell that story?

You have to show that it’s not just all sweet, glamour and loveliness. There’s the tensions that go with trying to get to this thing that people find so seductive. It’s made in fire, then you bring it out. It’s not made in a lovely and sweet way with everyone agreeing with everything. It’s made by sort of a fight and a tight compromise. That’s what makes the music so tough.

How does this movie show how hard it is to sustain superstardom?

I’m telling this film from a very personal point of view. It’s not a talking heads documentary, like a generic documentary made by the BBC. It’s made by me. Very personal, telling it from my point of view. Along the way I showed that it broke up my marriage to someone whom I completely loved and lost. In fact, all three of us ended up getting divorced. There was a lot of emotional stuff along the way, and a lot of people tried to come into the Police machine – as it became as we got bigger and bigger – and got destroyed by it. A lot of people just couldn’t make it being around the band. A lot of marriages went. It takes its toll.

The 2007 concert footage being added, how important was it to the overall movie to show you all remained a great band more than 20 years after breaking up?

The way I tell the story in the book, I tell it in a sort of flashback all through one day, which is the day we played at Shea Stadium, which was August 1983. This was the absolute height. We had the No. 1 album for four months with Synchronicity. We had the No. 1 song with “Every Breath You Take” for eight weeks. Not even Michael Jackson could get past us. We were it all over the world, no question. But at the same time, I knew it was the last tour. We were basically going to break up.

I choose to tell the story, I’m out one day, and we’re staying in this incredible mansion out on Long Island getting ready to play at Shea Stadium, and here are the sort of events through the day as I’m kind of passing through my earlier life, which ultimately leads to the Police. My life as a musician since I started as a kid.

The device that we used in the film was to use the concert footage from the 2007-08 tour, which gives it this incredible living presence. So it’s not all archival film from the early ’80s. It’s right now, or at least it was right then.

There was an element of tenderness added to the film when you mentioned how this was the first time that your kids would get to see you play as a member of the Police.

That was great. One of the nicest things of the whole tour, actually a very sweet thing, was that post-Police, I’ve got more kids, bringing them up and telling them, ‘Well, I used to be in this rock band, and I was really famous.’ They’d say, ‘Yeah, Dad.’

I finally got on the tour, and they were about 18. Of course, it was brilliant for me. I’d go, ‘Look, check it out.’ They really saw what I was talking about. They came to a lot of the really big shows. It was really great, a particularly nice thing.

What’s been the reaction from Stewart and Sting to the movie?

They’re very supportive. They both called me as this came out and I met with Stewart. This is not a bad thing. This is like the band going out on tour again. It’s everywhere at the moment. It’ll be all over the world eventually. It’ll be on HBO, and all the rest of it. It’s definitely going to have a life. All it does is extend the mythology for a few more years. Not hurting at all.

How does this movie help you to reflect on those years?

I don’t dwell, personally, too much on the past. Of course, it’s great to have this movie out. I expect most people would enjoy having a movie made about them. I certainly never expected it. One thing about the U.S. release, it’s nice for me finally… I’ve been around this project for a long time, to have this tangible excitement and to turn up at the cinemas to see it sold out then do the Q&As. All the activity that goes with it is brilliant so far.

Musically, I don’t dwell living in that time. It didn’t stop for me. That was just something, honestly, that I just passed through. I’m here in my studio right now, and I’ll go straight back down to the mixing desk and get on with the next track I’ll be making. It didn’t end with the Police. In fact, the thing that got me sorted out and back on my feet after the Police was done was going back into the studio to record.

How much do you play now?

There’s always something going on. I live in L.A. and I have my studio here. It’s very comfortable for me. I’m the only one who uses it, and it’s a great setup. One of the nicest things for me in life is to be in the studio and recording. Last year, I put out a great rock record with a brilliant singer in L.A. In fact, we came out to CSUN and did a live lunchtime session called Circus Hero. It was great. I don’t know where we’re going to go with that, but right now I’m finishing up a really beautiful instrumental album that’s very different from that. It’s sort of exotic and more experimental. I’m about two-thirds of the way finished with that. And prior to that I finished a film score. Then I go to Cannes for the film next month. Then I go to the Shanghai Film Festival, and I do some gigs in China, as I did last year. I keep going back to China. It’s one thing after another. There’s not a lot of downtime.

Do you keep up with your photography?

My sort of sub career of photography has continued quite well over the years, as much as I want to do it. Right now, I’ve got a photograph show at the Laemmle Royal in West Los Angeles. They do a very nice thing called “Art House,” where they make this short film and display whichever artist’s work. That show will be up for another three months.

Later this year I have a photograph show in Brazil and another one in Hong Kong in September. They all take thought and preparation. They don’t just fly out the door, you have to think about them. I’ve sort of got that down now because I’ve done it so many times. It’s sort of like a concert, doing a photograph show. It’s interesting, sort of a different subtle satisfaction.

After the Animals broke up, that’s when you enrolled at CSUN. How did that period of time center you after the breakup of the band and set you up for the Police?

It was an interesting time. It was a difficult time for me, because I was absolutely starving and had no band. I wasn’t trying to have a career. I stayed in L.A. partly because I got into CSUN, or whatever it was called at the time. I was able to study music formally, which I hadn’t done in England. I’d been in bands, and obviously was a player, but I started to do formal, classical music training. It was really the reason I stayed in L.A. Of course, that came to an end eventually and I returned to England. In short order I was in the Police, and I was armed to the teeth and I was absolutely ready to go for it.

I’d taken out that time to go to college here because just purely musical curiosity and wanting to deepen my involvement in music.

You’ve funded some scholarships here at CSUN in the music department. How did that come about?

I’ve been living in Los Angeles for a while, and I’m pretty close friends with the L.A. Guitar Quartet. John Dearman is now teaching there, and Steve Thachuk. When I was there, I was a classical guitar player then. You don’t forget these things. I’m obviously in a more fortunate position. Partly through John Dearman it occurred to me that I could maybe help out and provide some sort of scholarship for those who want to be classical guitarists. I certainly got enough out of it.

We started it last year. Steve organized it and hopefully he’ll set it up to do it again next year and make a whole evening out of it. That’s what I’m hoping. It’s an interesting little thing that’s come later in life that I wouldn’t have thought of. It’s a nice way to put something back and encouraging people in something that I always loved and starved for at the time. I really appreciate it.

All of us who are successful in music, which is a very tough game, if you really get across, you want to put some of it back to encourage the next group that’s coming up.

At some of the screenings of the movie, you’ve participated in Q&As with the fans. What’s it like hearing that feedback from the fans after all these years?

I find it quite rewarding. It’s not often you get to stand there and talk about all your stuff. I’ve done it quite a lot over my career. I usually do well if people ask interesting questions, then I get going. The ones that I’ve done here in L.A. have all been great. It’s nice to see all these people with so much enthusiasm. Certainly because the film goes down so well. By the time I get in front of the audience, everyone’s feeling pretty good and I enjoy it.

I would encourage people that if they really like the film then they should read the book. They’ll find that in the book there’s a lot more layers of the music life.

People seem to be very happy seeing the film. You always think there could be more. We actually have about another eight hours of footage (laughs). So we’re about to make part two, possibly. It’s going down so well, it’s ironic.

Andy Summers will participate in a special Q&A session following the 7 p.m. showings on April 12 and 16 at the Laemmle’s Royal on 11523 Santa Monica Blvd., Los Angeles 90025. P: 310-478-3836. Check local listings for all other showtimes.

experience

experience