CSUN Launches Project to Support Formerly Incarcerated Students

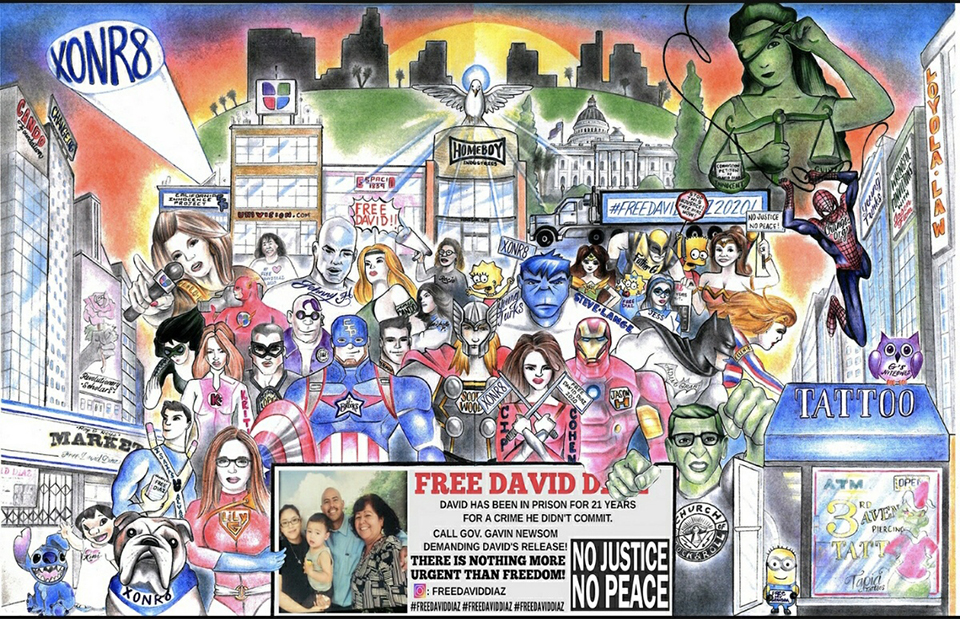

Artwork by David Diaz, who is currently incarcerated but soon to be released. CSUN students worked on the campaign to gain his freedom.

California State University, Northridge is now one of 14 California State University (CSU) campuses that are hoping to turn the schools-to-prison pipeline on its head, and instead create a prison-to-school pipeline that provides formerly incarcerated students with the support they need to succeed.

CSUN this fall launched Project Rebound, an initiative designed to help guide the students on their academic journey and connect them with campus liaisons committed to their success. The students also will be connected with community organizations and services to help them meet their basic needs.

“We are trying to get people who are incarcerated to imagine themselves on a university campus and to work towards that, so, when they come out, they have something waiting for them,” said Chicana/o studies professor Martha Escobar, executive director of the initiative on the CSUN campus.

Project Rebound originated more than 50 years ago at San Francisco State University as a way to matriculate people into the university directly from the criminal justice system. In 2016, with the support of the Opportunity Institute and CSU Chancellor Timothy White, Project Rebound expanded beyond San Francisco State into a consortium that grown to 14 CSU campus programs, including CSUN’s. Since 2016, Project Rebound students system-wide have earned an overall grade point average of 3.0, have a zero-percent recidivism rate, and 87 percent of graduates have secured full-time employment or admission to postgraduate programs.

CSUN’s Project Rebound this fall is providing support to nine students. Escobar said she expects that number to grow as word about the program spreads across the campus and in the community.

“One of our goals is to tackle the stigma associated with being formerly incarcerated,” Escobar said. “There’s a taboo associated with admitting that you were, at one time, incarcerated. That’s a big hurdle, and it keeps a lot of people from reaching out for help. We are working to build a community where our formerly incarcerated students feel comfortable, while respecting the fact that some of them are not going to feel comfortable coming out as formerly incarcerated.

“That is work we need to do — to help them contextualize their experiences, and not internalize so much guilt and shame,” she said.

Escobar said she has been impressed by how welcoming various offices across the campus have been in supporting students in the program.

“When our students need help, we don’t just give them a phone number, but actually connect them to someone with a name who is ready and willing to help them,” she said. “In each instance, when we’ve reached out to identify that contact person, we’ve found individuals who are truly committed to working with our students.”

As the initiative moves forward, Escobar said, Project Rebound will be facilitating conversations on campus about the criminal justice system, how Americans treat incarcerated people, and the support and expectations that American society has for the formerly incarcerated.

“It’s a conversation we’ve been having for a long time, and it’s one we continue to have,” she said.

experience

experience