CSUN Profs Argue Changing the Way We Mentor Can Help Tear Down the Vestiges of Historic Racism

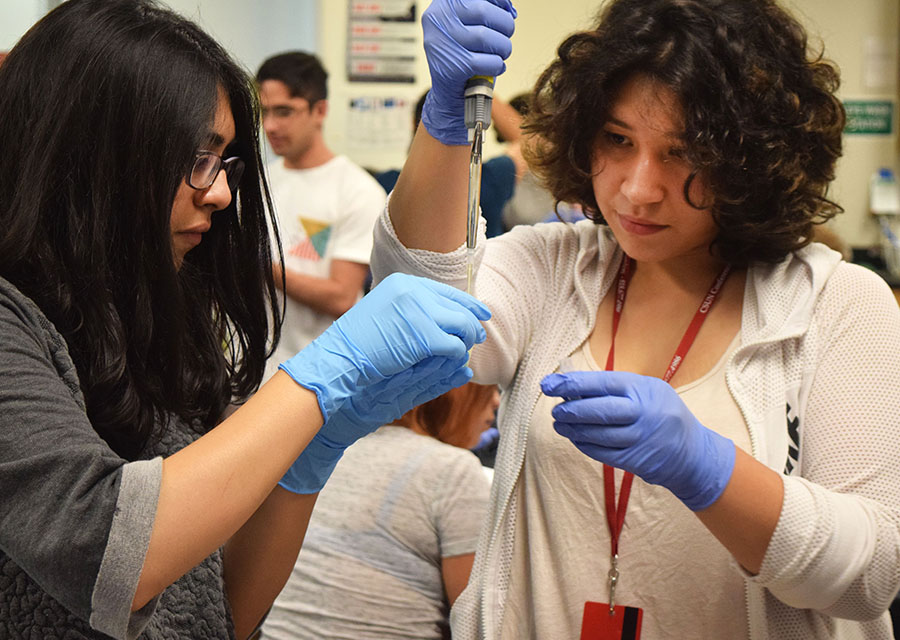

To better understand the role race plays in mentoring,CSUN psychologists closely examined what worked in the university’s BUILD PODER program, which is designed to increase the number of people of color who go into STEM fields. The photo of two students in BUILD PODER was taken prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo courtesy of Gabriela Chavira.

Conversations about race and the role it plays in all aspects of life — from education to employment — are becoming a regular part of the national discourse, and they have many people wondering what they can do to help dismantle the vestiges of systemic racism and create an environment that is truly inclusive and uplifting.

Three psychology professors at California State University, Northridge — Jose Vargas, Carrie Saetermoe and Gabriela Chavira — argue that the first step in making change is to recognize the inherent racism that lays at the foundation of societal institutions and all other forms of discrimination, and to learn how to counter its influence, particularly in situations such as mentoring.

“When we talk about racism, it’s usually in a very monolithic way,” Vargas said. “We think about racism as something that only exists in people’s minds or hearts. It’s a very psychological way of looking at things, and it has the effect of reducing the structural and institutional complexity of the problem at hand. Counter to this mainstream view, we study systemic racism by combining psychology with other disciplines and critical perspectives.

“Individuals exist in relationships, and these relationships exist in communities,” he continued. “These communities are governed by customs and laws, and these customs and laws don’t come out of nowhere. They are based, historically, on societal practices where one group of people maintain power and control over another — just like the lords and serfs of feudal times or, in the U.S., the masters and slaves. So many of our institutions grew out of that historical framework and developed structures and customs — including the rules that dictate the roles of mentors and protégés — that are influenced by colonization, white supremacy and patriarchy. If we recognize that history and change our perspective on how to mentor, we can empower a whole new generation.”

The views of Vargas, Saetermoe and Chavira — all researchers with CSUN’s Health Equity and Research Education Center — are drawn from a paper they wrote for the journal Higher Education, “Using critical race theory to reframe mentor training: theoretical considerations regarding the ecological systems of mentorship.” In the paper, the researchers asserted that racism is inherent to the structural makeup of the academic and scientific community, and contributes to the “push-out problem,” the phenomenon where talented students of color prematurely quit research and leave the scientific community altogether.

To better understand the role race plays in mentoring, they closely examined what worked in CSUN’s successful National Institutes of Health-funded undergraduate biomedical research training program, Building Infrastructure to Diversity Promoting Opportunities for Diversity in Education and Research (BUILD PODER), which is designed to increase the number of people of color who go into the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

Almost 300 students have participated in the program since its launch in 2014. More than two-thirds have been accepted into or are currently in master’s and doctoral programs. The program uses critical race theory — which assumes that the power structure in the United States is purposely designed to maintain white dominance, and seeks to transform that relationship into one of equity — to reframe mentorship and transform the mentoring relationship into one of equity and social justice.

“The mentoring of minoritized students really has to be less hierarchical and more horizonal,” said Chavira, one of BUILD PODER’s principal investigators. “Mentoring is always seen as top-down, me teaching you what I know. But the reality is, you are also learning from the students, and it’s often the mentor who is learning more about current issues. So mentoring, at its best, is bi-directional.

“At the same time, you have to give your students ownership of their projects,” she said. “They are part of the decision-making process. You are there to provide assistance and guidance when they ask for it. We are empowering them, giving them ownership of what they are doing and, in turn, a sense that they do belong in the scientific community.”

While the focus of their paper was academia, Vargas, Saetermoe and Chavira said what they learned can be applied to all aspects of life that involve one person serving as a mentor to another.

“One of the reasons we need anti-racist training is because structural racism in the United States has never been addressed, and it continues to impact the lives of various minoritized populations,” Vargas said.

“The system isn’t meant to be equal,” Saetermoe added. “But that doesn’t mean it has to stay that way. When we distribute knowledge to others who wouldn’t normally have access to it, we are changing the system and empowering those who traditionally have not had power.”

Vargas acknowledged that change isn’t easy.

“Acknowledging our prejudices can make us very uncomfortable,” he said. “We are not arguing that people should never prejudge or that doing so makes someone bad or immoral, because our brains are wired to make judgements. What we are asking is that people be aware of that judgement, and to ask themselves why they made that judgement. We need to deconstruct racist assumptions, whether they’re made by people or institutions, and challenge those attitudes and assumptions. Only when we are willing to confront uncomfortable experiences will we be able to make the change we need to truly be a more equitable society.”

experience

experience