ER Doctor’s Gift Honors Biology Professor for Changing the Trajectory of Her Life

In emergency rooms across the United States, nurses, doctors and hospital staff know never to say the “Q” word. The dreaded word isn’t “question,” “quarrel” or “quick” — it’s “quiet.”

It’s a rare time for an emergency room when the phones aren’t ringing and patients aren’t arriving, but that can all change in minutes, according to an ER superstition. As soon as someone remarks, “It’s going to be a quiet night, isn’t it?,” everything changes: Ambulances flood the ER with patients until it’s bursting.

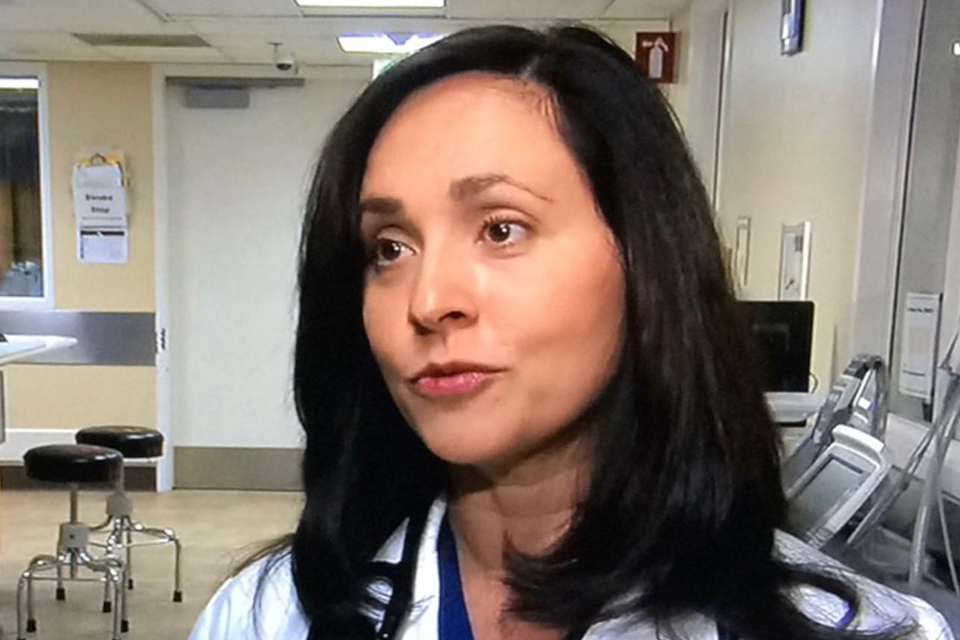

As a doctor of emergency medicine and Co-Medical Director of Burbank Emergency Medical Group at Providence Saint Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, it’s a situation that Celina Barba-Simic ’92 (Cell and Molecular Biology) knows all too well.

Barba-Simic’s only access to medical care as a child was the busy county emergency department, which “normalized” long waits, chaos and language barriers for the alumna. When she decided to pursue a career in medicine, emergency medicine was the only specialty she considered.

“Attending to people at times of crisis represents the greatest privilege of medicine,” Barba-Simic said. “I am most grateful to be able to alleviate anxiety and have an impact on patients’ acute medical needs…”

Barba-Simic always knew she wanted to work in medicine, but she never imagined that learning not to say the “Q” word would be such a valuable lesson — nor did she know that she would be drawn to the fast-paced world of emergency medicine.

Her path became clearer when she took a human embryology course with — and later joined the Center for Cancer and Developmental Biology of — esteemed biology professor Steven Oppenheimer at California State University, Northridge.

His influence on her was so profound that Barba-Simic recently made a gift to the CSUN College of Science and Mathematics to create the Dr. Celina Barba-Simic Biology Scholarship in Honor of Dr. Steven Oppenheimer.

The annual scholarship will provide one award for an undergraduate student with demonstrated financial need who is also conducting laboratory research in the College of Science and Mathematics’ Department of Biology.

She decided to make the gift, she said, after her daughters asked her a tough question: “Mom, how did you become a doctor?”

“One day they just asked me how I did it,” Barba-Simic said. “And I really tried to unravel all of those layers of skills and education.”

In unraveling 20 years’ worth of layers, Barba-Simic remembered her inspiring professor of human embryology.

“Dr. Oppenheimer at CSUN gave me the comfortable, accessible starting point where I could really start building those skills and seeing that there are possibilities,” she said. “He was absolutely essential.”

Her Time at CSUN

Oppenheimer, who has mentored thousands of students during his 40-year tenure as a CSUN professor, said that Barba-Simic stood out when she was an undergraduate.

“Celina had sparkle, spark and enthusiasm seldom seen in students,” Oppenheimer said. “The combination of her enthusiasm and my enthusiasm made for great success. Celina’s spark was inspirational.”

After getting to know the professor — now emeritus — Barba-Simic joined the famed Oppenheimer lab. “Being in Dr. O’s lab was awesome. He made it approachable and hands-on,” she said. “Everything was accessible. He encouraged every person that walked in there to do everything they wanted to do and helped them find ways to do it.”

In the lab, Barba-Simic helped research cell surface carbohydrates in adhesion and migration, to explore how cells’ surface sugar-containing receptor sites change during development. The study aimed to determine the function of those carbohydrates in order to find causes of cancer-cell spread.

Barba-Simic said the professor’s encouragement made a profound impact on her life.

“You walk in and he’s saying, ‘You’re wonderful and you’re the best!’ It was life-changing, his teaching and his classes,” she said. “It prepared me for medical school. I knew I had the study skills, the research skills and the knowledge base [to succeed].”

Although she learned many things from him, the most important idea the professor instilled in Barba-Simic was this: You can be a doctor if you want to be.

“I reflected on the impact my time in Dr. Oppenheimer’s lab had on my career,” Barba-Simic said. “He gave me the confidence to apply to [medical school]. Dr. Oppenheimer changed the trajectory of my life.”

Overcoming Barriers

A first-generation college student born in Mexico and raised in Pacoima, Barba-Simic and her parents came to the U.S. when she was three months old. She started working at the age of 15 and had two jobs by the time she was 16. She used her wages to pay for essentials.

“When I was graduating high school, I brought the UC application to my mom and was like, ‘How many of these boxes can I check off?’ I think the applications were around $50 each,” Barba-Simic said. “And she said, ‘Oh, honey, we can’t afford that and you can’t move away from home.’”

Financial and cultural constraints led Barba-Simic to CSUN, where she initially enrolled as a physical therapy major. Once at CSUN, she encountered cultural barriers to her education from well-meaning family and friends.

“I knew I wanted to be a physician, but everybody told me, ‘Oh, don’t be a doctor. It takes too long and you’re going to get married anyway,’” Barba-Simic said.

Despite the financial and cultural barriers, Barba-Simic paved her way to medical school by volunteering at the Veterans Affairs Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center, just a few miles east of campus, doing research and participating in on-campus organizations such as Chicanos for Community Medicine.

At the end of her undergraduate time at CSUN, Barba-Simic received multiple awards including Graduating Student of the Year Award from the Department of Biology and the Minority Achievers in Science Student of the Year Award. She also received multiple scholarships, fostering her appreciation of the financial needs of low-income students and later inspiring her to make a gift to aid those in need.

Barba-Simic made the gift to her alma mater in hopes of supporting “CSUN students that share similar challenges and career goals.”

As an involved undergraduate, Barba-Simic applied for — and later received — the National Institutes of Health Minorities Access to Energy Related Careers grant, with Oppenheimer’s encouragement, she said.

“The grant paid for two years [of undergrad], so I was able to stop working,” she said. “In the summer, the grant allowed me to conduct research in a Department of Energy lab and use the skills that Dr. O taught me.

“I was lucky to be at Lawrence-Berkeley National Laboratory working under Dr. Levy … where my job was to irradiate mice brain cell cultures, subjecting them to different levels of radiation and testing Bragg peaks using the linear accelerator. This was but a small part of the research that Dr. Levy used to perfect proton therapy for high-precision treatment of brain tumors and vascular malformations,” she added.

Perseverance

After graduating from Stanford Medical School, Barba-Simic completed a three-year emergency medicine residency at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, where she started work as early as 4 a.m. and ended as late as 7 p.m. — the following day. This meant Barba-Simic often worked 38-hour shifts and 120-hour weeks.

On top of extremely long hours, in the first three months of her residency, Barba-Simic became pregnant with her first child. She went to her fellow residents and asked to switch schedules around so that her vacation was at the end of her first year.

“Once I switched it all, I went to my residency director and said, ‘I have a plan.’ I did not miss a day,” Barba-Simic said. “I actually went into labor my last day. I guess you’re so used to, as a minority, working harder and trying to prove yourself that it’s just part of you.”

At the start of her residency, she was one of two women in a class of 12, but she didn’t let that disparity discourage her from accomplishing her goals and realizing her full potential.

“You make it happen,” she said. “I’m kind of tough — I think that’s the Pacoima in me.”

The influence that Oppenheimer had on her was invaluable, as was the education and training he provided. “Dr. Oppenheimer changed my life by believing in me and providing the opportunity,” she said.

To her fellow Matadors considering making a gift, Barba-Simic said: “Please take a moment to remember those individuals that have made a difference in your life while at CSUN. Reflect on your ability to share the fruits of your education with the next generation, your community and those in need.”

experience

experience