Preserving History During the Digital Age

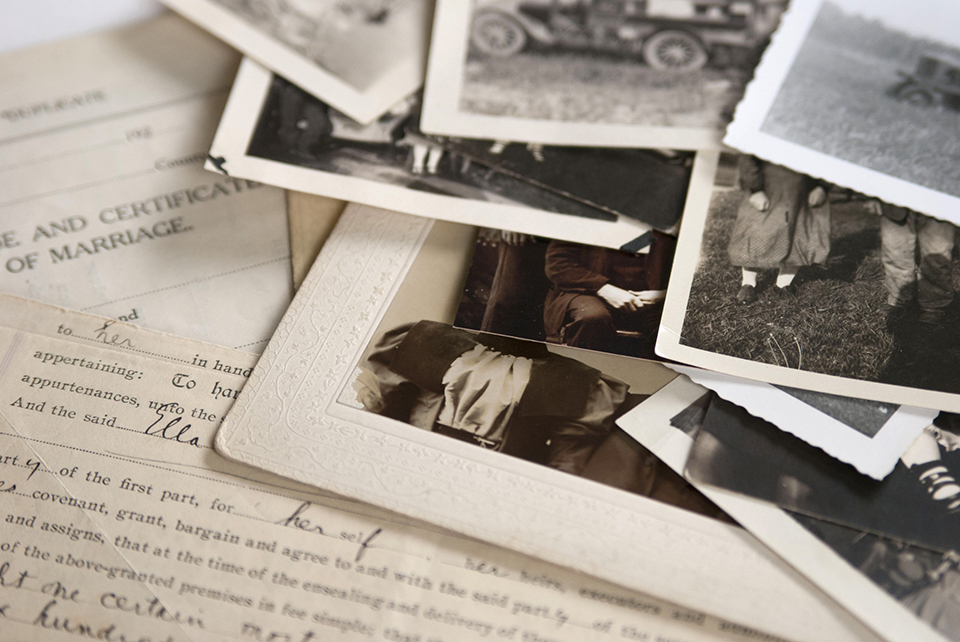

CSUN history professor Richard Horowitz and Ellen Jarosz, head of special collections and archives for the University Library, consider the preservation of historical memorabilia in a digital age. Photo by Megan Brady, iStock.

There’s a saying that once something is on the internet, it’s online forever. But as emails replace hard-copy letters and social media accounts are regularly deleted, what information will future historians have as they try to document the important events and gain insight into what life was truly like during the first half of the 21st century?

Those are questions California State University, Northridge history professor Richard Horowitz and Ellen Jarosz, head of special collections and archives for the University Library, are pondering as they look to the future of their fields.

“There’s this sense that what happens on the internet is never really gone — that it’s always out there, just waiting to be found,” Jarosz said. “And that’s kind of true. But what that means for us, archivists and historians, is that we are going to have to develop some new skillsets and learn to use different tools. As society has evolved, so has the way that it documents what happens in day-to-day life, and archivists evolve with it. We’ll adapt, just as we always have.”

Horowitz learned to do research by going through archives as a college student in the late 1980s.

“At the core of all of that was paper,” he said. “Today, there’s less paper and more things are digital or online. Preservation is the key. Preservation is about how you keep certain kinds of things. In some ways, the kinds of materials that are preserved shape the kinds of history that we do.

“Governments are historically very good about keeping documents,” Horowitz said. “The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, starting with the Obama administration, began to essentially store almost everything in an electronic format. So, when it comes to information about what governments are doing during this time, I think we’ll be fine.

“But when it comes to the history of individuals, then we’ll have to see,” he said.

Jarosz said people may not realize that much of their online presence — including their social media posts, particularly if they have engaged with public figures — is actually being captured by software designed to preserve what is happening.

“Whether it’s a big corporation or a university like CSUN, people realize that importance of preserving communication and other documents so that historians, archivists and other researchers decades from now can look back and get an understanding of what was happening during a certain time in history,” she said. “And that includes tweets between the President of the United States and those who follow him.”

When it comes to communication between less prominent entities and individuals, Horowitz said he’s still trying to figure out how those exchanges will be preserved. He noted that historians have traditionally studied letters sent to people to gain insight into the times in which they existed. “Letters that were written on paper that people kept,” he said.

“People exchange emails today, and I doubt very many of them print out and save their emails for posterity. Will their emails be saved in electronic form when they die?” Horowitz asked. “Will people be keeping their computers for posterity? When a writer decides to leave his or her papers to an archive, in the past, that was literally papers. But today, would it be hard drives? How many hard drives would that be, and would people be able to access them decades from now? And would they want to? It’s a complicated issue, and one that is constantly changing.”

Not all the changes are bad, he said, noting that when he started his career, he had to make an appointment with a library if he wanted to do a “database” search, “and I wasn’t really going to find very much historical material. So, to write a research paper, I was spending hours and hours going through paper archives,” Horowitz said.

Today, Horowitz, who teaches historical methods, trains his students to strategically search numerous databases available through CSUN’s University Library and some available on the internet for the historical data they need, “and they can find that information pretty fast,” he said.

Horowitz said he is more worried about the state of journalism. Newspapers chronicle the times and have offered a glimpse into the issues of the day and the lives of the people they served.

Horowitz noted that there is something “very special” about seeing and handling historical documents.

“I often wonder whether I would have gotten into this line of work if I didn’t have experiences with original documents when I was an undergraduate,” he said.

Horowitz was taking part in an exchange program at Oxford University in England as an undergraduate and trying to figure out a research topic when a professor suggested he go through a box of historical documents from 1800s China.

“The thrill of going through these documents that were written by people who were pretty famous at that time is indescribable,” said Horowitz, who went on to specialize in the history of modern China and world history. “I’ve always felt like I never enjoyed history the same way again. That experience shaped my research and the type of historian I became.”

Jarosz said she is not worried about the preservation of history in the digital age.

“Those old manuscripts aren’t being thrown away, and generations from now, we’ll still have the opportunity to be captivated by them,” she said. “There will also be new mediums in the future — we just don’t know what they are yet — that will also captivate people and enthrall then with the history of our time.”

experience

experience