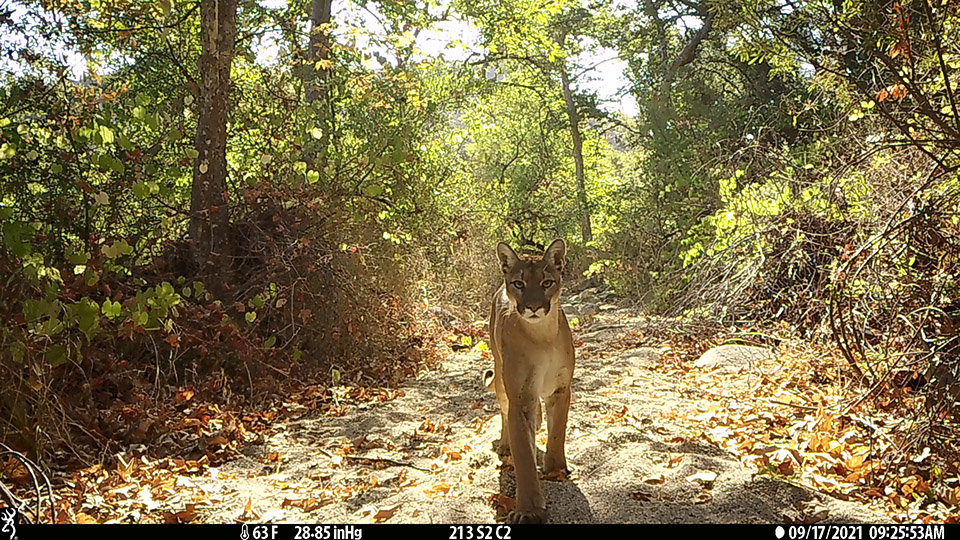

Urban Jungle: Protecting and Studying Mountain Lions and Southern California’s Diverse Ecology

A mountain lion stands in front of a camera near a predator deterrent device in the Cleveland National Forest in Orange County. Photo courtesy of UC Davis Wildlife Health Center.

The device Aaron Nanas built was broadcasting the cry of a distressed baby rabbit, which sounds a lot like a cranky human baby.

As a computer engineering student at CSUN, Nanas had originally designed and built this device to scare away mountain lions, the charismatic predators that can be devastating to livestock. But on this late August evening, his invention was perched on a post inside a perimeter, in a wooded area of the Santa Ana Mountains foothills, on a trial run to do the complete opposite: Could it attract the big cats?

Video footage of a field test soon arrived in Nanas’ CSUN inbox, with indisputable proof: In the footage, a large feline head pokes into the left side of the frame. Immediately, a second mountain lion joins her. Soon, there’s a third.

It’s a mother and her two kittens. The “kittens” are almost the same size as their mom — at the time, they were about a year old, nearly ready to go off on their own. The wary mother keeps a healthy distance from the device, but the two kittens enter the perimeter (which looks like a boxing ring) and saunter right up to the kids’-shoebox-sized device as they investigate the noise. One looks right into the camera, wearing the expression of a curious housecat.

Just as researchers had predicted, the sound of potential prey drew the big cats. Nanas was thrilled.

“I was in awe seeing the mountain lions,” said Nanas ’21 (Computer Engineering). “I was surprised to see them sniffing the device.”

Nanas’ experiment, which he completed as his senior capstone project, is just one example of the wide variety of work conducted by the university’s students and faculty to better understand and preserve Los Angeles’ unique urban ecology.

CSUN and Urban Ecology

A coyote roaming through a Los Angeles neighborhood. Photo by Tim Karels.

The College of Engineering and Computer Science offers myriad research and hands-on learning opportunities for undergraduates — in this case, to work on devices that benefit mountain lions, other wildlife and livestock. In the College of Health and Human Development, recreation and tourism management students and alumni work as rangers or docents in state and national parks, as natural resource managers, and as marketing and communications professionals who help members of the public safely enjoy the natural world around us, said Nathan Martin, acting department chair. Biology students and professors in the College of Science and Mathematics have researched urban carnivores such as coyotes and bobcats, smaller animals like lizards, geckos and rabbits, and numerous native and invasive plants.

“If you understand their behavior, you can potentially coexist with them,” said Tim Karels, a professor of biology who has worked with students to publish research on L.A.’s bobcats and coyotes.

This work benefits the world around us and the students who do the work. Nanas graduated in December 2021 and has gone on to do exciting work in another realm of science (more on that later), but researchers continue to build on his work.

Cat Rescue

An adult male and female travel together near one of Aaron Nanas’ devices on Orange County Parks property. Photo courtesy of UC Davis Wildlife Health Center.

Winston Vickers, director of the California Mountain Lion Project at UC Davis’ Wildlife Health Center, enlisted CSUN colleagues to work on a multi-functional device that could help protect livestock, and thus protect the threatened big cats who are often killed after preying on livestock, such as goats.

Vickers previously had worked with Xudong Jia, the former civil engineering chair at Cal Poly Pomona who now serves as associate dean of CSUN’s College of Engineering and Computer Science, on a project to identify options for potential wildlife crossings over I-15 in Temecula. At CSUN, Jia connected Vickers with resources and know-how to get the deterrent device project off the ground.

Mountain lions are an important part of California ecosystems, helping to regulate the movement of deer and other prey, to keep habitats in balance. If deer stay in one place for too long, they trample and wipe out the plants that smaller animals use for shelter. But the big cats are in danger of going extinct in Southern California — they have small populations that are isolated from each other by freeways, which have cut the cats off from huge swaths of territory where they’d normally hunt and roam. This isolation leads to inbreeding, which can reduce genetic diversity in the population and lead to reduced fertility and other genetic disorders.

The plight of mountain lions in Southern California captured national attention this past winter when P-22, the famed cat who crossed the 405 and 101 freeways to live alone in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park, was euthanized due to injuries he sustained when he was likely hit by a car a few blocks from the park. His encounters with humans and pets had increased in his final days, a sign of distress that led to a brief “manhunt” before his capture in a Los Feliz backyard. The city continues to mourn the loss of its adopted big cat, including a celebration of his life in February 2023 that filled the Greek Theatre to capacity.

P-22’s story helped inspire support for construction of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, a bridge connecting the Simi Hills and Santa Monica Mountains over the 101 Freeway at Liberty Canyon in Agoura Hills. Crews broke ground in 2022, and wildlife experts expect the crossing to help mountain lions and many other animals hemmed in by the freeway.

Vehicle accidents are a significant cause of death for mountain lions in the state, research shows, but not the most common cause, at least not among the ones tracked by GPS collar, Vickers said. When a mountain lion kills a pet or a member of a farmer’s flock, the aggrieved human can get what is known as a depredation permit from the state, to kill the responsible cat. (Mountain lion attacks on humans are extremely rare.)

Vickers asked Nanas to create something affordable that small farmers — who own, say, a couple of sheep, some goats or a few chickens, but no barn to shelter them at night — could use to protect their animals. By keeping livestock safe from mountain lions, Nanas’ device would make mountain lions safer from humans.

Nanas, who transferred to CSUN from Glendale Community College in 2019, chose to work on the project with electrical and computer engineering associate professor Shahnam Mirzaei as his advisor in February 2021. Nanas was attracted to the idea of being the first student to work on a new project, to create something brand-new, he said.

The project demonstrates that students working with professors in the College of Engineering and Computer Science can develop a product from conception to functioning product, Mirzaei said. And this one, he said, could have real-world benefits.

“It’s definitely important,” Mirzaei said. “Something you do for the environment, something that’s real.”

Trial and Error

Aaron Nanas.

The device Nanas designed was originally intended to be a deterrent — when its motion sensor was triggered, it would make noise, flash lights and make mechanical movements to scare away mountain lions from vulnerable livestock. Vickers said there are no devices currently on the market that have every feature he envisioned.

Nanas set out to find parts that he could combine and program into an affordable device. Through trial and error, he settled on a $20 microcomputer that could work with all the parts he needed — it could play a speaker, interface with a small touch screen and control a motor. (The motor was going to power a separate motion feature to distract the animals, but Nanas didn’t have time to make that feature work.)

Later, the project’s goals changed: Instead of deterring mountain lions, Vickers decided he’d like the device to attract them. By drawing the animals near, UC Davis researchers could collect hair for DNA isolation as the animals entered the perimeter. Cameras positioned around the device enabled the researchers to collect photos and videos to assist in identifying individual cats for a partnership with U.S. Geological Survey researchers.

So, Nanas pivoted. This mostly required switching the audio files to different sounds. Instead of using loud noises or human voices to scare the lions away, Nanas used sounds of vulnerable prey.

“Aaron did a good job building his prototype out of off-the-shelf hardware that wasn’t too expensive,” Vickers said. “That’s something the electronics students are better at sniffing out: How to do something inexpensively, because they’re sometimes building other things on their own.”

Testing and Innovation

One of Aaron Nanas’ field devices. Photo courtesy of UC Davis Wildlife Health Center.

Nanas sent four prototypes to Vickers’ team in late August 2021. The devices were tested mostly in the mountains and foothills surrounding Orange County. The videos with the mountain lion family were captured on Audubon Starr Ranch Sanctuary, in Trabuco Canyon, Vickers said.

The team placed the devices near a site baited with roadkill deer. They surrounded each one with a perimeter of posts and ropes covered in tape and a sticky substance that helped capture fur samples for DNA testing. Both kittens in the videos rubbed against the tape when they entered the ring to investigate the noise.

After the field tests, Nanas tweaked the devices — replacing some components, updating the software, modifying the speaker so the sound would be smoother. With the addition of a manual switch, the device can now serve as a deterrent or attraction.

Tests of the deterrent features — especially loud sounds like human yelling — have also shown that the device works, and most mountain lions would avoid a site completely after encountering the devices a couple of times, Vickers said. Predator-deterrent devices could be useful in protecting livestock worldwide, Vickers said. Zoos and wildlife sanctuaries also have expressed interest in the technology.

What’s Next

A mountain lion sighted on a trail in Orange County. Photo courtesy of UC Davis Wildlife Health Center.

In recent months, a national award-winning high school student has been building on Nanas’ work, trying to develop a system for multiple devices to communicate with each other to form a network of livestock-protection devices. It’s also possible that other CSUN students could continue work on the project or create other, similar devices.

As for Nanas, he’s been busy since graduation, looking above and beyond California — way beyond. Even before his graduation, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory hired him as a flight software engineer. He contributes to the design and verification of simulation models that test the functionality of flight electronics components, to be used in the lander that will help retrieve and bring back samples from the Martian surface. He also develops the software necessary to validate the simulation models. The lander is scheduled to launch in 2028, and the samples could return to Earth in approximately 2033.

Nanas gained a ton of experience in his CSUN classes and a six-month internship at Keysight Technologies in Calabasas that made him marketable, and his work on the deterrent device specifically gave him more confidence to write software, he said.

“We just started with an idea, and we ended up with something tangible,” Nanas said. “And it works.”

experience

experience