CSUNSat1 Slated to Launch to International Space Station in Less Than 2 Weeks

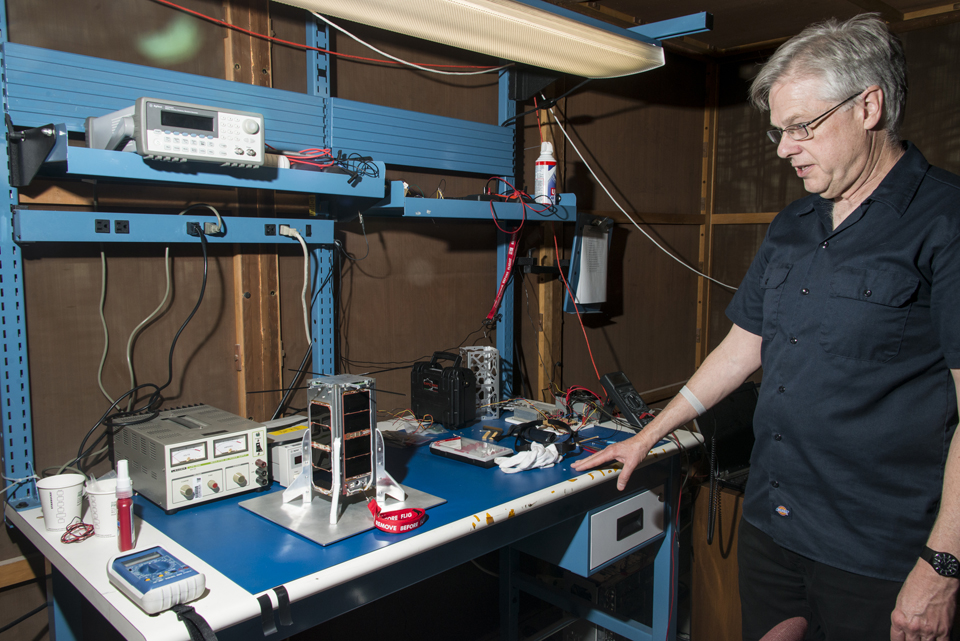

CSUN electrical and computer engineering professor James Flynn with CSUNSat1, a cube-shaped satellite about the size of a backpack (sitting in the center of the work table). The satellite will launch in less than two weeks. Photo by Lee Choo.

In less than two weeks, California State University, Northridge and Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) will be waiting for a Morse code signal from the university’s first stellar explorer — CSUNSat1, a cube-shaped satellite about the size of a backpack, signaling its successful venture out in space.

Sharlene Katz

CSUN electrical and computer engineering professor Sharlene Katz said the satellite project is the first of its kind for the university.

“We’ve never done anything like this before,” she said. “The satellite hardware and software were designed and built from scratch. The ground station was done from scratch. We want to run the mission. It’s time. We feel confident in it.”

The satellite will launch into space on March 19 from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla., propelled by an Atlas V rocket. It will head to the International Space Station, where it will be deployed into space in April next year. CSUN’s ground station command and mission control, located in Jacaranda Hall, will communicate with it after its launch via radio.

One of the most challenging aspects of the mission will be switching the power source from a general standard battery to JPL’s prototype, according to CSUN electrical and computer engineering professor James Flynn.

“One of the key tests is that the experimental battery has to power the satellite itself,” he said. “It’s like changing your brain without losing your mind. You are doing a transplant. The batteries are not equal; the characteristics are not the same. So, not only do we change the battery, but also how the battery is taken care of . . . all in 50 milliseconds.”

JPL collaborator and CSUN computer engineering alumnus Carl Chesko agrees the most delicate task for the satellite will be the power source switchover. He has faith in it running smoothly.

“This is something that is never done, like, ever. Part of the reason it is not done is because you never need to,” he said. “Why would you? You don’t need to take the battery out of your phone. If you do, it dies. For this project, we need to continuously run without batteries for .05 of a second. But, at the core, this has been running for more than two years. The core of this works.”

Flynn said one of the rewarding aspects of the mission for the students was learning the importance and value of the work they can do at CSUN.

CSUN computer engineering undergraduate Armen Arslanian was charged with creating the deployment code for the satellite’s four antennas. For him, the most challenging yet rewarding aspect of the project was learning to create a computer code that would communicate with the satellite’s code between the main satellite computer and the antenna’s computer.

“The antenna has its own brain,” he said. “The satellite’s brain is talking to the antenna’s brain. The issues start there and you have to take care of everything. In this part of the mission, you can’t do anything if something goes wrong. What you can do has to be taken care of now because nothing can be done from the ground if [the antennas do not deploy].”

Katz lauded the students for their hard work on CSUNSat1.

“This is a university; it’s about the experience,” she said. “We continue to find little things [to fix] on our list, but it’s really shrinking down. We’ve invested so much in learning about [small satellites]. We didn’t think anybody could do it as well as we could, honestly. We’d like to try it again.”

Flynn added that while everyone is excited for the three-year project to come to a close, there will be some sad feelings when the satellite is dropped off at NASA.

“I know what’s going to happen,” he said. “We’re going to take it to Houston. They are going to give us the pin [from inside the satellite that is pulled to arm the satellite] — that is what you are left with. Then we’ll have empty cradle syndrome. We’ll sit there and wonder ‘what will we do now?’”

For now, the CSUNSat1 team will get to sit tight at the ground station and wait for that Morse code signal hailing it from space, informing it of a successful first mission.

For more information about CSUNSat1, please visit www.csun.edu/cubesat.

experience

experience