BUILD PODER Conference at CSUN Examines Science, Race and Racism

California State University, Northridge scholars, students and other leaders hosted more than 100 Los Angeles-area high school students Nov. 2 for a half-day conference that examined racism, scientific research, artistic expressions on race and how to increase diversity in the sciences. The campus’ second-annual BUILD PODER fall conference, Science, Race and Racism, was organized to showcase BUILD PODER, the university’s new research training program that is supported by a $22-million, five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) — the largest grant in CSUN’s history.

In its second year, the program has grown to 105 students for 2016-17, with more than 100 faculty members involved as research mentors. BUILD PODER stands for Building Infrastructure to Diversity (BUILD) and Promoting Opportunities for Diversity in Education and Research (PODER). The program aims to increase diversity in biomedical research fields and prepare participants for Ph.D. programs. Students receive funding for 60 percent of their CSUN tuition, faculty mentorship and a paid research position.

The free conference also was sponsored by CSUN’s MOSAIC program — Mentoring to Overcome Struggles and Inspire Courage — and the university’s Diversity Program Consortium. The event took place in the Northridge Center of the University Student Union and featured BUILD PODER student research poster presentations, keynote speeches by two respected scholars from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), and the University of Washington, as well as a social justice art installation created by MOSAIC mentors (CSUN students) and their teen mentees.

MOSAIC is a long-running and acclaimed CSUN program that pairs CSUN student mentors with youth at risk for educational failure, gang and family violence, drug and alcohol abuse, and emotional trauma. Since 2004, more than 500 CSUN students have worked with nearly 1,500 students enrolled in Los Angeles Unified School District continuation high schools. The service-learning program matches sociology students with teens as peer mentors and advisors.

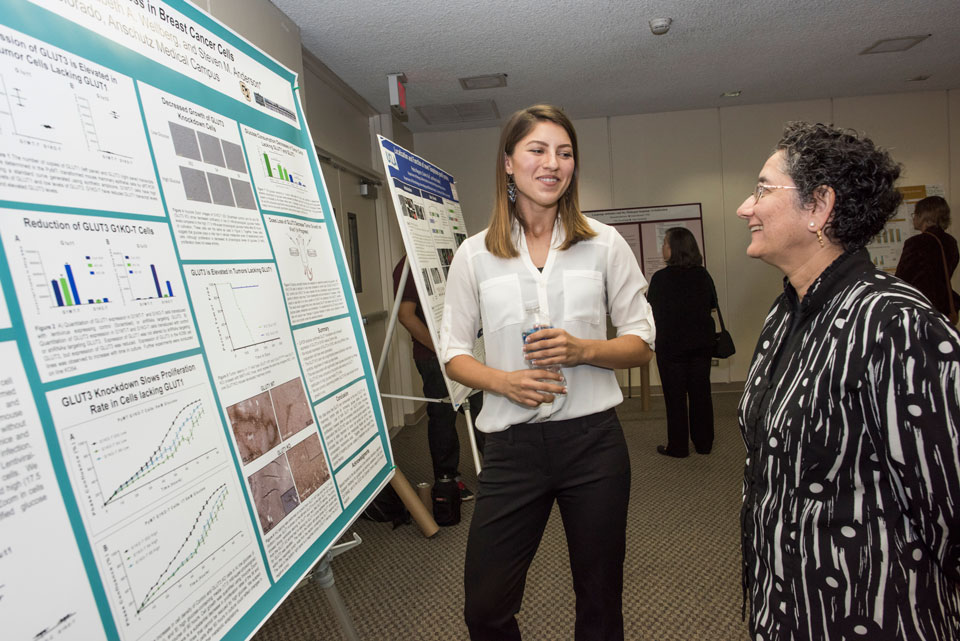

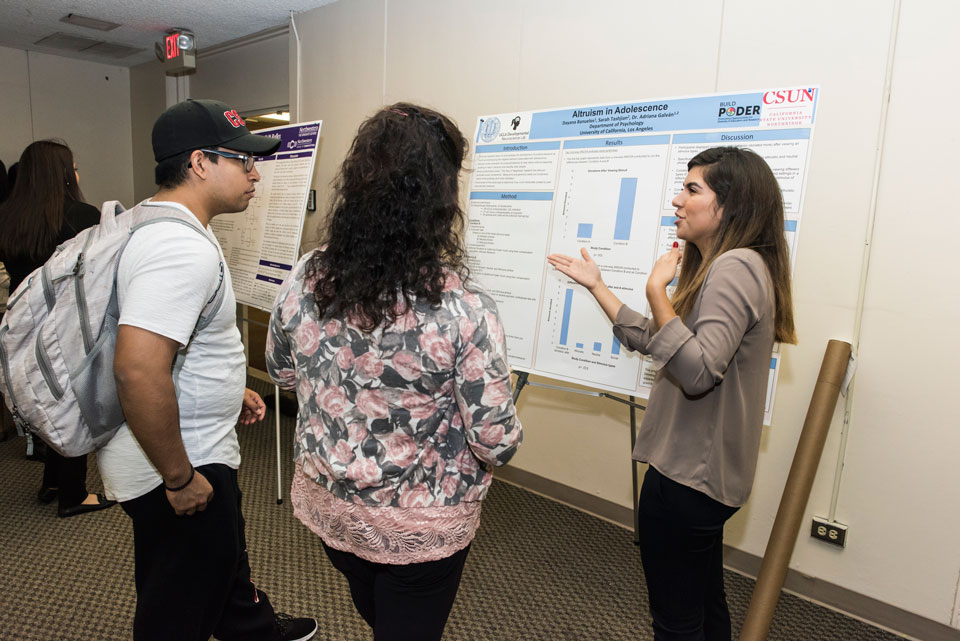

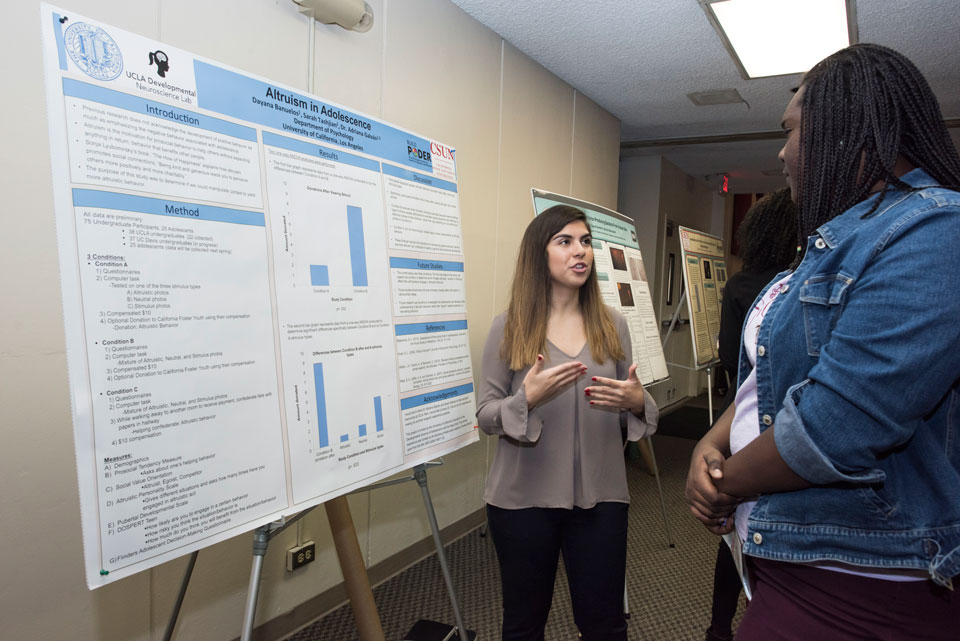

The first hour of the conference was devoted to showcasing the large posters displayed by BUILD PODER student researchers. The posters summarized the initial results of their summer projects or year-long scientific research, and the students answered questions and gave mini presentations to their peers, professors and members of the wider community.

The undergraduate researchers must select and apply for their own mentors, from the program’s pool of CSUN faculty mentors, said Gabriela Chavira ’94 (Psychology/Chicano Studies), psychology professor and student training core director for BUILD PODER. It’s just one aspect of preparing the undergraduates for the kind of work and responsibilities they’ll have to take on in graduate school or post-doctoral programs, Chavira said.

The program also includes professional development workshops and requires (and funds) the students to present their research in at least one national or regional conference per year. Many of the students noted that the CSUN fall conference was great practice for out-of-town conferences — which are, for most, their first time traveling away from home to a professional event.

Over the summer, biochemistry senior Ashley Ward conducted research on tumor cell metabolism in breast cancer at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. The summer program was an extension of her experience during the 2015-16 academic year, when she worked at CSUN with biology professor Eric Kelson — while juggling a full course load. On Nov. 2, she used the session at the BUILD PODER conference to fine tune her poster talk, before presenting at a national conference in Florida later that week. Ward also was juggling midterm exams and applying for doctoral programs for next year.

“I’m not gonna lie — it’s tough juggling all of my classes, the research and getting all of my applications out,” Ward said. “But this is great practice for next week [in Tampa, Fla.]. I presented this summer to the University of Colorado faculty, but it’s great to do this here at CSUN.

“Conducting cancer research in the [summer] program has definitely solidified my interest in studying cancer,” Ward said. “I know that I want to work in drug development or treatment of some type of cancer.”

At CSUN, Ward works in the lab with Kelson, chair of CSUN’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. Kelson’s team is trying to develop anti-tumor agents, looking for a compound that can selectively enter a tumor cell and bind to DNA — strong enough to prevent DNA replication needed for cell division, Ward said.

Dayana Banuelos, a junior and psychology major, also presented at the BUILD PODER conference, where she presented her preliminary findings from summer research in brain development and altruistic behavior in adolescents at the developmental neuroscience lab at UCLA.

“Our goal was to focus on positive behaviors of adolescents,” said Banuelos, 20, who is the first in her family to attend college. Her parents didn’t finish high school. “So much research on adolescents has focused on negative behaviors.

“Before, I thought research was only for graduate students,” said Banuelos, who works with CSUN Psychology Department Chair Jill Razani in a neuropsychology lab during the academic year, studying older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. “BUILD PODER has been a really helpful program! When I apply for graduate schools, I’ll have conferences, presentations and experiments under my belt.”

Other undergraduate research presented Nov. 2 included topics such as hookah smoking and its effects among CSUN students, and stem-cell tissue regeneration.

BUILD PODER is a large regional program that partners with six community colleges (East Los Angeles College, Los Angeles Valley College, Los Angeles Mission College, Pasadena City College, Los Angeles Pierce College and Santa Monica College) and five local, doctoral-granting institutions (Claremont Graduate University, UC Irvine, UCLA, UC San Diego and UCSB).

The program’s aim is to increase diversity in the biomedical research fields and open the “pipeline” to research careers, Chavira said.

On the other side of the large Northridge Center room, the MOSAIC art installation was the largest of its kind ever organized on the CSUN campus for the program’s teen mentees and CSUN student mentors. The temporary exhibit focused on themes of critical race theory and the high school students’ challenges and frustrations.

After mingling around the exhibit and touring the CSUN campus, the high school students from throughout Los Angeles stayed for presentations by the two guest speakers. Miroslava Chavez-Garcia, professor of history, Chicana/o studies, and feminist studies at UCSB, gave a riveting talk entitled Science, Scientific Research and Youth of Color: the Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility and California’s Carceral State.

Chavez-Garcia’s research on the history of the California juvenile justice system focused on the use of so-called “science” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to study juvenile inmates. She looked at archived case files for young men and boys at the Whittier State School (then known as “reform school”) from the 1890s to the 1940s. She noted the disproportionate confinement of minority youth, which started as early as the 1930s and ’40s, and she spoke about “scientific researchers” of the time who created links between race and intelligence.

“The goal was to contain this ‘menace,’” Chavez-Garcia told the conference audience, about the state’s eugenics program. “And how did they contain this menace? Compulsory sterilization. (California passed a law legalizing forced sterilization in 1909.) California sterilized more than 20,000 people in the 20th century.”

She wrapped up her presentation with a stark and tragic look at the abuse suffered by the boys at Whittier State School (closed in 2004) during the 1930s, ’40s and beyond — and the two suicides in 1939 and 1940 that sparked a Los Angeles Examiner expose, court hearings and subsequent reforms.

Karina Walters, an enrolled member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and associate dean for research at the University of Washington (UW), spoke next on Indigenizing the Academy: Demystifying Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science.

“The bridging of what we call Western science and indigenous knowledge has already happened in some ways,” said Walters, who is also the director and principal investigator of the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute at UW. “It’s time to acknowledge it. From an indigenous point of view, all things are connected — and now, Western science is catching up to that.”

experience

experience