Creating During A Pandemic: Virtual Residency Program Students Delve into the Heart of Art

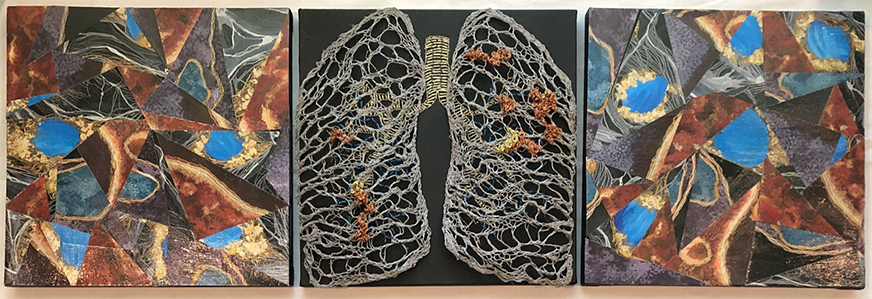

Visual artist Kate Berman ’20 shifted her work to reflect the coronavirus. Here, using yarn, embroidery thread, as well as gouache paint and ink, her art portrays a study of the lungs. Photo courtesy of Samantha Fields.

Pre-pandemic, Alexis Ramos ’20 — a multimedia installation artist — would fire her ceramic tiles in California State University, Northridge’s kiln shed, a massive building always bustling with activity as students load and unload carts of ceramic work.

As part of professor Samantha Fields’ Art 429 Contemporary Studio course, Ramos and the other aspiring artists — student painters, photographers, sculptors, multimedia artists — found mental fuel and inspiration honing their craft in the university’s printmaking studio, sculpture lab, dark room and other creative spaces.

So when Fields had to scramble in March to reimagine her senior capstone course, she asked herself:

What’s the most critical thing my students learn?

The answer, she realized, wasn’t defined by physical space. “The core of my class asks, ‘Why are you an artist? What is your art about?’” she said. “We can do that anywhere.”

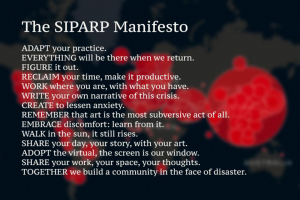

In a matter of days, Fields launched the Self Isolation Pandemic Artist’s Residency Program (SIPARP) online, which would not only prep her students for the real world, but inspire them to rethink art and its process. The framework, so popular she opened it up to other CSUN students, would eventually serve as a model for art faculty at Chico State, UC Berkeley and other universities nationwide.

Isolate, Unplug, Create

As fate would have it, one week before California’s “safer at home” orders came down in March, Fields had asked her students to research artist residencies — competitive programs in which the artist unplugs from regular life to focus on creating. When the pandemic hit, she sent students a congratulatory email notifying them they’d been accepted into CSUN’s “newest residency program.”

The guiding principles of the virtual residency program. Photo courtesy of Samantha Fields.

The new class rules, as residency: First, create a home workspace, document it online, and then keep creating and sharing their artwork — along with their thoughts and feelings on the art and the process. The SIPARP framework also included Zoom conference calls with Fields, as well as peer critique sessions and resources to inspire and connect each other.

“I joined CSUN after the [1994] Northridge earthquake, taught through 9/11 and taught through the last recession, but nothing has been as destructive as this,” said Fields, a professor of art and painting in CSUN’s Department of Art. “But as artists, we reflect the world around us in our work and find ways to innovate in everything we do.”

A Shift in Perspective

Art viewed in a new context. Photography by MFA student Teresa Morrison.

Pre-quarantine, Master of Fine Arts (MFA) student Teresa Morrison would make a 200-mile trip every weekend to see her parents and take photos of the homes in their senior community. As she shared her work online, she began to see it through a new lens.

“Today, I view these images and can’t help being overwhelmed by a sense of senior isolation and family separation,” she said. “The meanings of photographs change over time.”

Visual artists such as Kate Berman ’20 saw her focus change from studies of the heart and brain, to art reflecting the coronavirus. “Although there was a shift in content, the message behind my work remained the same: what is apparent on the outside might not be a true reflection of what is occurring within our bodies,” said Berman. “SIPARP has taught me to turn challenges into opportunities to grow and create art.”

With no access to CSUN’s kilns, Alexis Ramos ’20 turned to her family oven to fire her ceramic tiles. Photo courtesy of Samantha Fields.

As for Ramos’ ceramic tiles, she found herself quickly adapting and using the home oven in her family kitchen as a sort-of kiln.

“Part of what this class did was teach students how to be artists without being in school,” Fields said. “Artists in the world don’t have anyone telling us what to create, or access to all these different facilities. I used SIPARP as a bridge to transition them into the world they were going to graduate into anyway.”

At the Core

Ultimately, the new project centered around self-isolation created what the students most needed during the pandemic: a community.

Its impact radiated far beyond CSUN. When art colleagues at Chico State, UC Berkeley and West Valley College in Saratoga, California, reached out to Fields to inquire about how she organized the SIPARP framework, she was happy to share it and then highlight those new sister residencies on her webpage, she said. Professors from Otis College of Art and Design, USC, Parsons School of Design in New York City, and St. Catharine University in St. Paul, Minnesota, also have reached out to her. Fields said she hopes one day to create a traveling exhibition featuring this collaborative effort.

For now, the art professor is thrilled at what her students gained through SIPARP: a renewed sense of what their art is about — and the knowledge that their creativity has no physical bounds.

Brian Ramirez ’20 uses calligraphy to document the pandemic. Photo courtesy of Samantha Fields.

“Everything I needed was in the studio — the clay, the wheel, the kilns and the tools,” said Brian Ramirez ’20, who initially found himself struggling without the structure of a school studio. Forced to think outside the box, Ramirez discovered two new mediums, calligraphy and paper-mâché, and is set to start his MA at CSUN in the fall.

The SIPARP experience will serve graduate student Matthew Chan ’20 well in his next step as an artist, he said. Chan was admitted to Chautauqua School of Art’s prestigious artist-in-residence program in New York, which this year is being held online — a process and environment with which Chan is now intimately familiar.

“Spring 2020” by digital illustrator and designer Eugenia Diaz ’20. Photo courtesy of Samantha Fields.

“I’ve seen you struggle and stall and get back to work again,” Fields said to her graduating seniors during their celebration on Zoom in May. “I’ve seen you find new ways to express your ideas when the old ways weren’t possible anymore. This is what it means to be an artist. We might not know what the world will look like in the coming year, but that doesn’t mean we can’t help shape it with our work. Art reflects the world around us, and as we move out of this pandemic, CSUN students and the work they make will become part of the record of this time.”

experience

experience