Judy Baca Returns to CSUN to Talk Public Art

Judy Baca ’69 (Art), M.A. ’80 (Art) paints it black. And red. And chartreuse, emerald green, turquoise, fuchsia and cyan. The world-renowned muralist took her passion for color, Los Angeles and its youth from then-San Fernando Valley State College in the late 1960s and turned her paints into a movement. More than four decades later, Baca returned to her alma mater to preach the beauty of civic murals and their ability to transform community.

On April 30, Baca spoke at the third and final installment of California State University, Northridge’s annual Commerce of Creativity Distinguished Speaker Series. More than 100 art students, faculty and community members turned out to hear Baca discuss the transformative power of art at the Kurland Lecture Hall of the university’s Valley Performing Arts Center. The Mike Curb College of Arts, Media, and Communication sponsors the annual lecture series.

“A mural is not an easel painting made large,” said Baca, now the artistic director of the UCLA/Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) Cesar Chavez Digital Mural Lab. “It is related to those who lift the brushes to help paint it. … It is a choreographed dance between team members. … It amplifies community voice.

“At their highest moments, murals can reveal what is hidden — and be the catalyst for change.”

In her lecture, titled “Excavating Land and Memory Through Public Art,” Baca used slides and anecdotes to bring audience members along on her journey from fledgling murals in the barrios of 1970s Los Angeles, to her latest work on the traveling “World Wall” mural with indigenous people in British Columbia, Canada.

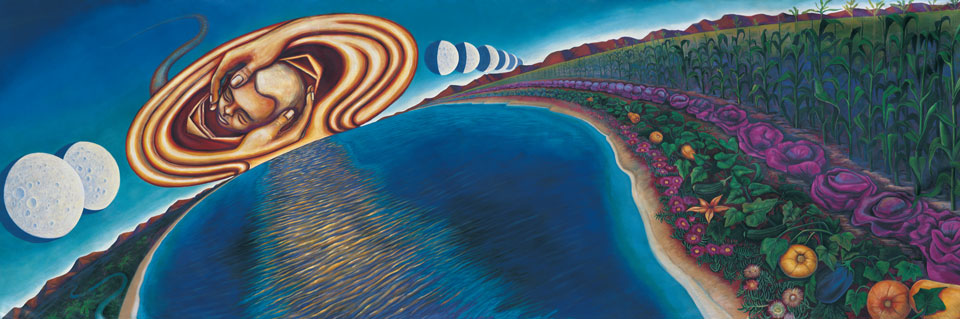

One of her best-known works is “The Great Wall of Los Angeles,” which lines a flood-control channel in the east San Fernando Valley. Baca supervised the creation of the mural, the world’s longest at 2,740 feet, by more than 400 at-risk youth and their families. In her early 20s, Baca founded a city-wide mural program and then launched the Great Wall in 1976.

“The story of Los Angeles, where I was born — like many cities — begins on the banks of a river,” she said, sharing slides of the river’s natural, wild state and its concrete flood-control channels. “I saw the concreted arroyos — the largest public works project in America — as scars on the land. They were eyesores. To me, they represented the hardening of the arteries of the land.”

The Great Wall, painted along the Tujunga Wash — a tributary of the Los Angeles River — tapped the talents of local artists, oral historians, ethnologists, scholars and community members to capture the multicultural history of California from pre-history through the 1950s. Its panels include scenes of civil rights activists, native peoples, even Holocaust survivors living in L.A.

“We worked to tattoo the sand, where the river once ran,” Baca said. “I was a participant, as well as an initiator. … The Great Wall was a recovery of a history that was lost, and it was my history. There’s no way I could have predicted the snowball effect [it would have].”

Baca shared that an interviewer once asked her, what would she say to her 24-year-old self at the start of that lifetime project?

“Absolutely nothing,” she told her CSUN audience, as the crowd laughed. “I wouldn’t want to tell my 24-year-old self that ‘this is going to be way too hard, and you’ll never get rid of these kids!’”

Baca recruited underprivileged youth, gang members — even combining rival gang members in the same painting crews, making “clear that the mural was a neutral space,” to chronicle the cultural history of L.A., said CSUN art professor Mario Ontiveros in his introduction of Baca.

“She exhibits a tireless commitment to nurturing … communities and cities,” said Ontiveros, one of her many mentees. He noted that Baca’s grandmother, upon viewing her senior art exhibition at CSUN in 1969, asked, “What is it for?”

This question “inspired (Baca) and guided her on her journey and career,” he said.

As she painted her first murals in the barrios of L.A., Baca became known in the communities as “the mural lady.” She soon won worldwide attention and acclaim for painting the city’s urban freeways for the 1984 Summer Olympics. Her work is included in the Smithsonian Institution’s permanent collection.

Baca has taught art in the University of California system since 1981, beginning at UC Irvine before moving to UCLA’s Cesar E. Chavez Department of Chicana/o Studies in 1996. At SPARC’s digital mural lab, she works with students to create collaborative mural designs using digital technology.

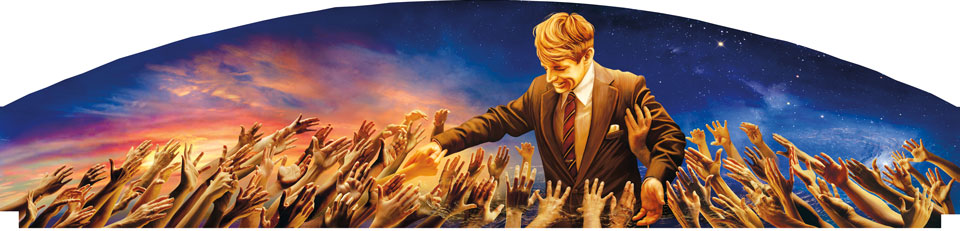

In 2010, she completed the Cesar Chavez Memorial at San Jose State University and the Robert F. Kennedy monument at what is now Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools — formerly Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel, the site of Kennedy’s assassination in 1968. She called this “one of the most difficult sites I’ve had to address.”

The California Endowment recently awarded SPARC a grant to preserve and restore the Great Wall’s historic sections, now more than 30 years old. The wall, her life’s work, helped Baca “know I could do anything,” she said. “The process transformed me — it made me fearless, easy with criticism. Bring it on.”

experience

experience