Young Alum Catapults from CSUN to Launching Navy Jets

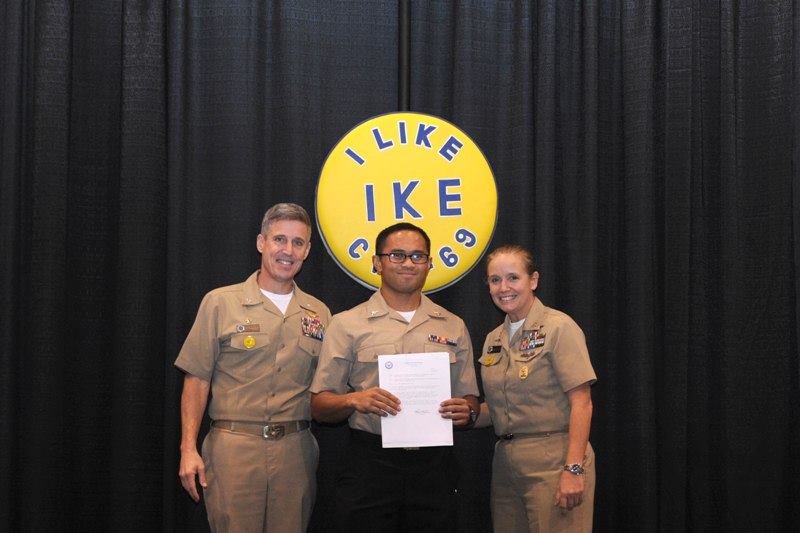

Petty Officer 2nd Class Mark Dalmacio has spent much of the past five years on an aircraft carrier at sea, catapulting fighter jets into the sky.

Until the United States Navy’s USS Dwight D. Eisenhower returned to port this summer for maintenance and upgrades, Dalmacio ’11 (Screenwriting) served as a catapult captain — the guy who pushes the “fire” button, the last move in a complex series of steps required to give jets enough momentum to lift off from short carrier runways. As an enlisted man with the rating of Aviation Boatswain’s Mate – Equipment, Dalmacio helped launch approximately 100 jets per day for thousands of ground-support missions to Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria.

“It’s exhilarating,” said Dalmacio. “I’ll never forget being on deck the first time a 48,000-pound jet went from 0 to 160 mph in under three seconds, and just feeling the heat and the exhaust and the wind when it flies past you, and smelling the steam. It’s mesmerizing.”

This occupation was a bit of a plot twist for Dalmacio, who attended California State University, Northridge with dreams of writing movies and TV shows. But CSUN, he said, gave him the tools to succeed in the military, preparing him for a leadership role in one of the most high-pressure jobs on the planet.

Dalmacio grew up in South Lake Tahoe, Calif., the son of a Philippines army veteran who emigrated to the U.S. in the early 1980s (before Dalmacio, 29, was born). Mark Dalmacio completed his bachelor’s degree and enjoyed himself at CSUN — even serving as vice president of recruitment for the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity — but he opted to find a more stable income than an entry-level job in the entertainment industry.

During his last semester, he enlisted in the Navy, wooed by the prospect of travel, an exciting job and a significant pay raise from his retail job. In May 2012, he reported for his five-year assignment with the Eisenhower, nicknamed the “Ike.”

Top Gun, in Real Life

Like all aircraft carriers, the Ike is a floating air base, a massive piece of military equipment that can be deployed offshore where “something crazy is happening,” as Dalmacio put it. The nuclear-powered ship is 24 stories tall, nearly 1,100 feet long, and its flight deck is 252 feet wide, according to the Navy website. Despite its size, the Ike’s runways are about 300 feet long, nowhere near the more than 2,000 feet of runway that jet fighters typically need to get airborne. To compensate, aircraft carriers use catapults.

That’s where Dalmacio came in.

He worked his way up to catapult supervisor during four deployments (including one as a volunteer aboard the USS George H.W. Bush), each lasting six months or more in the Mediterranean Sea, Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. The “birds” he helped launch included F/A-18 Super Hornet fighter jets, E-2 Hawkeye surveillance jets, EA-18G Growler electronic attack jets and C-2 Greyhound cargo jets, Dalmacio said. He started as a crewman on the flight deck, doing a lot of the grunt work such as installing fittings on aircraft.

Dalmacio compared an aircraft catapult to a double-barreled shotgun, with the jet riding on top of the barrels. The catapult is powered by steam, generated by nuclear reactor-heated ocean water. When Dalmacio pushed the “fire” button, two doors opened that released the steam and propelled the two barrels down the track.

By his fourth deployment, Dalmacio was the central point of contact for the carrier’s “catapult No. 2,” supervising about 15 people handling all the maintenance and operations of that catapult. (The Ike has four catapults.)

Dalmacio and his team monitored steam pressure and braking systems, raised the jet blast deflectors and made sure every critical component worked properly. For example, if the doors holding the steam open too slowly, the jet won’t get off the deck with enough speed and will launch itself into the sea. His team performed maintenance on the barrels that transport the plane down the deck, and the launch shock absorbers that handle 0 to 160 mph in less than three seconds.

“There’s a ton, a ton, of maintenance,” Dalmacio said.

Diverse Campus to Diverse Navy

The young sailor’s time at CSUN prepared him for a leadership role, he said. Recruiting for his fraternity taught him how to appeal to each individual’s motivating forces, Dalmacio said. CSUN’s diverse campus also taught him how to relate to a military population more diverse than the U.S. as a whole.

“The diversity at CSUN helped prepare me to succeed, not just at the day-to-day aspect of my job, but on the interpersonal aspect, the social aspects,” Dalmacio said. “You go to CSUN and meet so many different types of people, so many people and languages and cultures. That helped me with my ability to relate to people as a co-worker and especially as a leader.”

The “fire” button for the carrier’s catapults is located on the far edge of the flight deck, alongside the runway. At that station, Dalmacio had his back to the water. Before launch, he had to confirm that air, hydraulic and steam pressures were good, that mechanics gave the thumbs up for flight, and that the flight deck was clear. The first time he pushed the button, Dalmacio said, he took a deep breath, exhaled, and sent a 55,000-pound jet loaded with ordnance on its way.

“It’s really nerve-wracking the first time you push the button because it’s the last thing that happens,” Dalmacio said. “That’s crazy.”

The Matador faced other, more physical and physiological challenges at sea. For up to 50 days at a time, he could see nothing on the horizon but ocean. Onboard ship, there are no days of the week, just work days stretching 12 to 18 hours, sometimes more. On the flight deck in the Persian Gulf in July, the temperature sometimes exceeded 120 degrees. Dalmacio couldn’t eat much, because he had to squeeze meals between launch cycles. When he could get away, the lines on the “mess deck” were always long, so he often just made himself a quick sandwich.

But the Ike docked in places such as Spain, Greece, France, Portugal, Bahrain and Dubai, and Dalmacio had a few days of shore leave to look around. And the job itself was awesome, he said.

“To be a third person watching flight operations on the flight deck, it’s like a dance,” he said. “You see all these people working robotically. ‘Birds’ up, this happens, this happens, this happens, this happens, boom. All right, repeat. Catapult 1, catapult 2. One and 3 are launching at the same time. Two and 4 are launching at the same time. Boom, boom, boom.

“All right, we gotta recover him, so these have to stop launching,” he continued. “So now the plane’s coming in, now it’s landing, now another jet takes off. It’s where you understand the term ‘military precision.’ When you watch how precise we are, how quick we are, how good we are at our jobs, it’s mesmerizing.”

Dalmacio’s last assignment on the Eisenhower was readiness training, spending two or three weeks at a time practicing for combat missions in case a sudden need for deployment arose. This summer, Dalmacio began a three-year assignment as a barracks supervisor at Naval Base Kitsap in Bremerton, Wash.

“My job at sea is infinitely more exciting than my job ashore,” he said. “I’m basically an RA (resident advisor), but I do much less work.”

If Dalmacio decides to re-enlist at the end of the assignment, he said, he’ll likely go back to sea. He’s not screenwriting now, but his time in CSUN’s program definitely shaped his life, he said.

“The things you learn in college should not just guide the things you do in life, but guide the way you see life,” Dalmacio said. “So I see life as a big story. What am I doing to make my story better? The things I’ve learned along my journey have helped improve my life and my story.”

experience

experience