National Arab American Heritage Month: Reflecting on Diversity and Unity

April 1 marks the start of National Arab American Heritage Month, a month dedicated to the 4 million Americans with Arab roots in 22 Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) countries, including Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Sudan (Arab American Heritage Month 2023). Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-Michigan) and Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Michigan), a first-generation American born to Palestinian immigrants, introduced a resolution in Congress in 2019 to honor each April and the contributions of Arab Americans.

“It is my hope as a strong and proud Arab American in Congress that our nation can uplift our contributions in the United States by supporting Arab American Heritage Month,” Tlaib said of the resolution (the bill remains pending). In 2021, President Joe Biden recognized April as National Arab American Heritage Month.

This year, the heritage month celebration coincides with Ramadan, the Islamic lunar holiday where Muslims fast, abstaining from food and water from dawn to sunset, every day for a month (this year, March 23- April 21). Muslims make up a substantial percentage of the Arab population, at 93%, but live alongside those of Coptic Orthodox, Christian and Jewish descent (Pew Research Center). We asked CSUN students who identify as Arab American about their Arab culture and influences, and what this month means to them.

Safaa Kaddoura, 22, Palestinian American: Born deaf to Palestinian parents, Kaddoura has come to learn the importance of many important Arabic traits and facets — besides language. She reflected on the way she communicates with her “loud family” and noted that she started speech therapy at a young age. While her family mostly communicates with her through English, that did not stop them from learning the basics of Sign Language. Her English is stronger than her Arabic, Kaddoura said, but she remains “very proud to be Palestinian.”

Safaa Kaddoura, 22, Palestinian American: Born deaf to Palestinian parents, Kaddoura has come to learn the importance of many important Arabic traits and facets — besides language. She reflected on the way she communicates with her “loud family” and noted that she started speech therapy at a young age. While her family mostly communicates with her through English, that did not stop them from learning the basics of Sign Language. Her English is stronger than her Arabic, Kaddoura said, but she remains “very proud to be Palestinian.”

Food is an incredibly important avenue for cultural self-expression, the fourth-year psychology major said.

“The food brings me closer to my culture,” Kaddoura said. “I love cooking and expressing myself through food. I can share that with the people I love, and I’m thankful that they embrace the food that I make. It just keeps me so sane.”

Christina Dakhil, 21, Syrian American: Dakhil grew up in Porterville, a city about two hours north of Northridge. Dakhil, a third-year biology major, said the active Syrian community there taught her the importance of unity and finding comfort within a community.

Christina Dakhil, 21, Syrian American: Dakhil grew up in Porterville, a city about two hours north of Northridge. Dakhil, a third-year biology major, said the active Syrian community there taught her the importance of unity and finding comfort within a community.

“Most of my friends are Syrians. However, I do feel [that with] every Middle Eastern that I am introduced to, there’s always that little bond. [I typically won’t lose touch] because we have that unity bond that we were raised with,” she said.

Like many Arab Americans, Dakhil has struggled with representation — and proper recognition, she said. For example, on most government forms and official paperwork, there’s no accurate ethnic category for people who identify as Arab American.

“I remember on the [U.S.] Census, I put ‘White’ only because I think there was no other option,” she said. “I’m not White. No way — I didn’t learn how to speak English until I was 10. And you’re making me say I’m White? My dad still doesn’t know how to form a proper sentence [in English], but he’s considered White.”

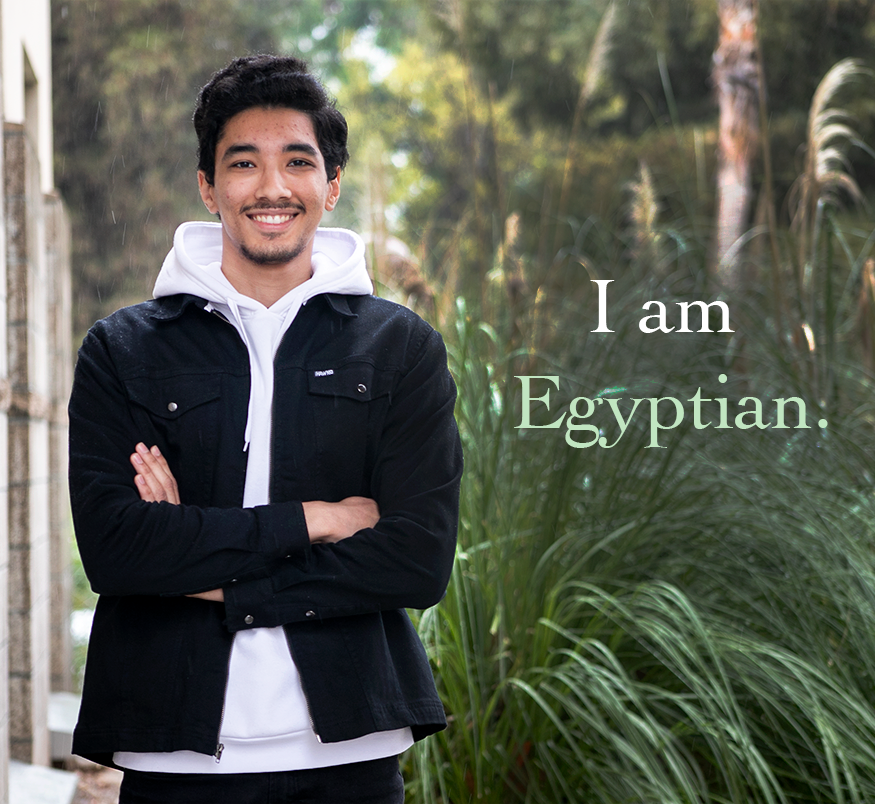

Angelo Ghatas, 20, Egyptian: A third-year psychology major, Ghatas came to the U.S. when he was 10 as a refugee to escape Coptic Christian persecution. As he adjusted and eventually assimilated, he said, he came to find his community in the San Fernando Valley.

“I do feel the most connection to Egyptians, because well, for me, I go to church every Sunday, and so the people that I see there are people I’ve seen every Sunday since I came to America,” he said. “I already feel like we’re a family. Because I played on the basketball team for my church, that definitely strengthened the bond between me and other Egyptians that were my age.”

As Coptic Orthodox, Ghatas observes rituals and traditions such as the vegan-based Holy Great Fast, which runs from Feb. 27 to April 15, and allows for preparation for Easter.

Holiday seasons often reveal interesting crossovers between his religion and the overall Egyptian culture, he said. While Ghatas is not an observer of Ramadan, he mentions positive elements, including the yearly tradition of new Ramadan shows premiering.

“One of the things I love about Ramadan is the [TV] shows that come out. They’re always really good. That’s one of the things I get excited about. In general, I feel like there’s more unity [during Ramadan]. If you visit the region, you will find more connection than division.”

Ghazi  Kanaan, 21, Palestinian American: A third-year engineering management technology major, Kanaan traces his Palestinian roots to Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Alternating between visiting the two countries and living in America, his Arab roots influenced the choices and connections he made, he said. Before CSUN, he started his higher education journey at Sacramento State University.

Kanaan, 21, Palestinian American: A third-year engineering management technology major, Kanaan traces his Palestinian roots to Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Alternating between visiting the two countries and living in America, his Arab roots influenced the choices and connections he made, he said. Before CSUN, he started his higher education journey at Sacramento State University.

“I like [meeting] people with like-minded cultures. So when I went to Sac State and saw this big [Arab] population, a couple of my friends and I [created] the Arab Student Union there, and I served as the president before I transferred down here,” Kanaan said. “The biggest thing about it to me was just giving all [the students] somewhere that they can come and be together. … There are a lot of international students living far away from their families and need [a more familiar environment].”

Kanaan works in the restaurant industry, and he is a practicing Muslim observing Ramadan this month, despite the challenges of being around food at work.

“This is my first Ramadan away from home,” he said. “I do enjoy the month, [and I get to] be in touch with my spiritual side.”

Sam y Couja, 22, Syrian: Couja was born and raised in Syria, until he came to the U.S. when he was 10. The third-year marketing major and self-described ambivert (a person with extroverted and introverted features) still remembers the challenges he faced as a new immigrant.

y Couja, 22, Syrian: Couja was born and raised in Syria, until he came to the U.S. when he was 10. The third-year marketing major and self-described ambivert (a person with extroverted and introverted features) still remembers the challenges he faced as a new immigrant.

“When I first moved here, talking to people was difficult, obviously because of the accent and the language barrier. I went to an international school [and] I kind of knew some English, so it [didn’t take as long to assimilate]. Later, I became more confident, and although I like to keep my groups small, I don’t feel like I have an accent or stand out [negatively].”

He appreciates both American and Syrian culture, Couja said, reflecting on the kindness of the Syrian people he remembers from childhood.

“They are more respectful. They have more discipline,” he said of his fellow Syrians. “They communicate things easier. They don’t resort to violence instantly.”

experience

experience