The Composition: A Photojournalist’s Journey to the Pulitzer Prize

CSUN alumnus and Associated Press photojournalist Julio Cortez poses in front of a police line in St. Paul, Minn., during coverage of the George Floyd protests on May 28, 2020. Hours later, he took a photograph that eventually won a Pulitzer Prize. (Photo by John Minchillo)

Fire walked across power lines like an army of ants marching toward a morsel of food. Bottles and concrete flew through the evening sky. Electrical pops, the crashing sound of landing debris and angry voices provided the evening’s dissonant soundtrack.

CSUN alumnus Julio Cortez walked down a Minneapolis street that resembled something he had only seen in apocalyptic movies. He stopped for a moment, then took off his gas mask. His face felt the wave of heat one feels when they open an oven door.

The fear of being mistaken for a police officer ran through his mind because he was dressed in black and wearing a Kevlar vest. To the enraged protesters, law enforcement was public enemy No. 1.

The 41-year-old had another fear — not returning home to Baltimore to see his wife and two toddlers again.

He freed a hand from his Canon 1DX Mark II and took a drink of water from a plastic bottle to soothe his dry throat. Then he noticed a tall man walking alone down the center of the street.

The man was holding an American flag upside down.

The moment reminded Cortez of a December morning in 2019 after the first Impeachment of Donald Trump, when Cortez, an Associated Press photojournalist, snapped a photo. An American flag had somehow come undone from a loophole and hung upside down from a pole with the Washington Monument in the background. Cortez recognized the symbolism: The U.S. flag flown upside down is a signal of distress or danger.

Cortez shifted back to the present in Minneapolis, in the same city where three days earlier a white police officer knelt on the neck of a Black man, George Floyd, for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, killing him.

Cortez thought this lone protester may have been quietly sending a message of distress or danger, as others audibly decried Floyd’s murder.

Cortez grabbed his camera, then followed the man for 40 seconds.

His ISO setting on the Canon was at 6400. The aperture was at F4. Cortez composed himself and the image. He pushed the shutter button at 11:59:38 p.m. on May 28, capturing one of the most iconic images of 2020 — a photograph that helped tell one of the most globally affecting stories of a generation. For the next few days, the picture appeared in newspapers, websites and newscasts around the world. It eventually led to Cortez winning a Pulitzer Prize for the Associated Press in 2021.

All Julio Cortez ever wanted in life was a shot. And despite his fear and the surrounding chaos, he took it.

“This was a moment for me to step up and show that I can do this. It was a chance for me to make it whatever I could,” Cortez said. “Kind of like coming to the States. All I wanted was just a shot, just give me a shot. Give me a shot to go to school. Give me a shot to work at a newspaper.”

Cortez’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a protester carrying a U.S. flag upside down next to a burning building in Minneapolis on May 28, 2020. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

A Passion Found in America

The Pentax K1000 camera was regarded as easy-to-use — perfect for the experienced amateur or the professional photographer. The camera had a thin, boxy shape with a black body and a satin chrome top. An advertisement from the 1970s called it a “steal at the price.”

A used K1000 sat inside a San Fernando Valley pawnshop and caught the eye of then 17-year-old Cortez.

But he couldn’t take it home immediately. The price tag was $200 — too much for a teenager to justify spending all at once, and too much to ask his parents for.

So, he put it on layaway and made payments $10 at a time.

Photography was just a hobby — a supplemental way to document stories. The actual storytelling Cortez wanted to do was as a sportswriter covering the Los Angeles Dodgers.

His father, Julian, was the first member of the family to come to the U.S. from Mexico. He arrived the week the Dodgers won the World Series in 1988.

Nearly a year later, Cortez, his mother, Rocio, and two younger siblings, Nancy and Carlos, made their first attempt to join their father and live in the U.S. They took a flight from Mexico City to Los Angeles but were stopped at the airport and sent to a detention center, where they were held for a week. Their room had nothing but a stained, blue mattress and a lightbulb. They had to peer through a window with steel bars to see sunlight.

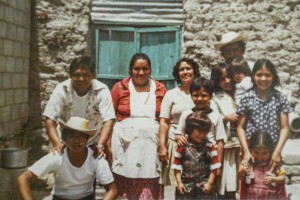

Members of Cortez’s paternal family with Julio, second from top right, held up by his aunt Claudia in the patio of his grandparents’ home in Tepexpan, Mexico. (Courtesy of Julio Cortez)

Rocio decided she didn’t want to put her children through this. Instead of waiting for a judge to decide the family’s fate, she took the kids and boarded a bus packed with other immigrants to Tijuana, Mexico. The family arrived back in Mexico and tried to enter the U.S. the next day.

Cortez, 10 years old at the time, stood with his family at the fence dividing the U.S. and Mexico. As they planned their crossing, Cortez hesitated and cried. His mother asked him what was wrong.

“I knew we were doing something bad,” he recalled. “I was like, ‘I don’t want to go to the U.S. Nobody ever asked me if I wanted to come to the U.S.’”

The family, smuggled by a coyote, crossed the border and eventually met up with Julian to begin a new life in America and in the San Fernando Valley.

Cortez found a passion quickly — journalism. At Madison Junior High and Grant High schools, he wrote for the school newspapers. He knew education was his ticket to a better life. So after high school, he went to community college with an eye toward pursuing a career in sports journalism.

Cortez, far left, poses with the staff of The Madison Journal, the newspaper at Madison Middle School in North Hollywood, in the spring 1993 semester. (Courtesy of Julio Cortez)

At 19 years old, he got a permit to work in the U.S. and landed a job at the bottom of the sports journalism profession for a big paper: covering high school sports for the Los Angeles Daily News.

Cortez would take in a few hours of a boys soccer match or football game, return to the Daily News office in Woodland Hills and turn in about five paragraphs, sometimes 10 if he was given a little more ink space from his editors.

He wanted to make an impression, though. In addition to a notepad and a pen, he would take his Pentax K1000 to games and capture the action on film. So enthused, he brought the photographs to show his editor and staff photographers.

One staff photographer gave Cortez discouraging feedback: “You focus on the writing. We’ll focus on the photography.”

“I still think about that day because I think back and see that not only did I have people who encouraged me along the way, but there were people who tried to stop me from chasing my dreams,” Cortez said.

Those words motivated him. But a moment in history brought a new focus to his life.

Journalist to Photojournalist

Cortez was in a political science class at Pierce College on Sept. 11, 2001, a few hours after two planes had flown into the World Trade Center in New York City.

The discussion about what had just happened made him feel that he had a duty, and he became eager to leave class. Once the class was over, he raced to the Daily News building, only a few minutes away by car.

“I’m going to the paper because they probably need somebody to read copy, or run copy, or do whatever. I want to help,” Cortez recalled thinking.

Every day Cortez worked, he’d take the same path inside the Daily News building, passing the photo department on the way to the sports desk. On this day, he walked the path and could see there was no open space where the photographers did their work — tables and desks were covered in printouts from the horrific acts that had happened earlier in the day. Recognizing the historic importance of the day, Cortez stopped to look at photos and read captions.

One photograph stopped him: Associated Press photographer Suzanne Plunket captured a moment on a New York City street when a cloud of smoke from a fallen tower seemingly chased a group of men. In the foreground is a man in business attire, wearing a backpack. He is running, causing a slight motion blur. His mouth is agape and the look of fear is clear on his face.

“I looked at it and I was like, ‘Wow, this is history. I need to do this. I want to do this,’” Cortez said.

Cortez continued to hold onto his education like it was his lottery ticket. But now, photography would be his direction.

The problem was his undocumented status. To attend a California university, he would have had to pay out-of-state resident fees. Instead, he spent seven years taking community college classes because they were affordable.

In July 2003, at age 24, he went before a judge to plead his case for permanent residency. The judge noticed that his petition listed him as a minor, which is how long it had been since he first applied to obtain a status change.

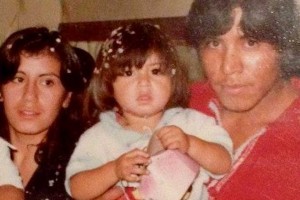

Cortez, center, with his parents, Rocio, left, and Julian, in 1980. (Courtesy of Julio Cortez).

The judge told Cortez that she would have to deny the request.

Cortez was prepared to advocate for himself, and through excited, hurried words, he made his case.

He showed the judge a binder with pages of accolades — journalism awards, a letter of congratulations from his community college president for his journalism work, a Los Angeles Times scholarship notification, Los Angeles Marathon finishing times and school diplomas.

“This is the track record of somebody that’s been doing something really good here. I’m not trying to take away anything from anybody,” he told the judge. “Here’s the evidence! This is what you want in your country!”

She agreed and approved Cortez’s permanent resident application.

With his residency status changed, Cortez enrolled at CSUN for the fall 2003 semester, eight years before the California Dream Act was signed into law. The act allows undocumented students who meet certain eligibility requirements to pay the same tuition and fees as resident California students at public universities.

Sí, Se Puede

Though getting to CSUN was a triumph, his seven years at community college gave Cortez the itch to get through his time at the university as quickly as possible.

He had a plan — shoot photographs, get them published and build a portfolio. He started with CSUN’s bilingual publication El Nuevo Sol. He worked with and developed a friendship with a fellow young journalist named Salvador Hernández, who later crossed over to the university’s English-language campus newspaper the Daily Sundial and became its news editor. Hernández wanted Cortez on his team again.

“He was super talented, and I wanted to recruit and try to get people into the Sundial that were not just great, but especially during the time it was a little bit challenging to find people of color to recruit into The Sundial,” recalled Hernández, now a reporter for Buzzfeed.

Cortez, bottom left, poses with a group of CSUN journalism students in the Fall of 2003. (Courtesy of Julio Cortez)

Cortez accepted Hernández’s invitation and began shooting photographs for the Daily Sundial.

But after one semester, another opportunity opened up.

Hernández accepted an internship in Dallas for the Dallas Morning News Spanish publication, Al Día. The hiring editor told him the paper wanted to add another intern. Hernández floated Cortez’s name.

Soon, Cortez was hired, and they went to Dallas together.

Hernández admired Cortez for his versatility — he had a knack for capturing the story in one photograph, and he could write. But there was one other quality that stuck out.

“Honestly, his hustle, which I think was unique to him,” Hernández said. “Julio would shoot anything and everything. He was great at shooting sports and shooting news, which I think was rare for a student. … He wasn’t just taking shots and making them look good, which is a challenge already, right? He just really had a gift already at that time to be able to tell a story just with the image.”

To take the internship, Cortez left his job at the Daily News and took a semester off at CSUN.

Rain fell on Cortez’s first day working in Dallas. He saw an opportunity to make an impression immediately and went out to shoot photographs.

Lightning struck that evening, and Cortez captured an image of the 72-story Bank of America Plaza building with its silhouette neon green lights, a purple sky and an illuminated white bolt striking down from the heavens.

The next day, he excitedly showed the photo to his editor.

“This is garbage,” Cortez recalled the editor saying. “There’s no subject. You missed the moment.”

The focal point was wrong. The image was filled with noise from street lights and power cables, and the lightning bolt was blurred.

Hernández was watching the scene play out inside the newsroom and couldn’t hear what was being said. He spoke with Cortez immediately afterward.

“He’s just like,” Hernández paused, “devastated, is the right word.”

The editor, though, showed Cortez a weather photography book, and the young photographer studied it quickly. Fortunately for Cortez, the thunderstorm raged on, offering him a second shot.

Cortez took a photo of lightning in Dallas on June 2, 2004, during his internship at Al Dia newspaper. (Courtesy of Julio Cortez)

In an editorial meeting, the interns were told to be careful that day, maybe take it easy. Instead, they decided to head out in Hernández’s Ford Explorer and chase a thunderstorm.

The pair found a parking lot next to a hospital with a wide view of the Dallas skyline. They each carried a camera, and to protect the equipment, Cortez and Hernández covered them with plastic bags.

They shot pictures for an hour as the rain beat down.

Lightning struck again, and Cortez captured it. Picture No. 172 of 245 photographs was the one.

Hernández also recorded video with a handheld camcorder that night.

Cortez went back to the newsroom and showed the photo editor his work. And to prove it was authentic, he showed video to the editor.

The editor, Cortez recalled, was floored and asked how he improved so swiftly.

“’I need a little bit of instruction,’” Cortez told the editor. “’You tell me how to do it, and I’ll do it. I’ll figure it out.’”

With more experience on a professional stage, Cortez gained confidence, and his photography continued to improve. When he came back to CSUN, he returned to the Daily Sundial as its photo editor. But he also had a goal in mind: take on more internships.

He earned internships at papers in San Angelo, Texas, and Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

And he earned his journalism degree at CSUN.

Cortez poses for a photograph moments before graduating from CSUN on May 30, 2006. (Courtesy of Julio Cortez)

“It’s so symbolic to me. I’m the first in all my extended family to graduate from an American university. For me, graduating from CSUN really meant ‘Sí, se puede.’” Cortez said.

He purposely used the Spanish phrase, which means, “Yes, it can be done.” The words are a rallying cry popularized by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta to represent the determination of the United Farm Workers movement in 1972.

As Cortez took the stage in front of the CSUN Library to collect his bachelor’s degree in 2006, he had a rectangular cardboard sign and a foot-high, lime-green cardboard arrow attached to his mortarboard. The sign read, “immigrant.”

After his name was called and he was handed his diploma, Cortez approached the microphone and shouted “Sí, se puede!”

Coming Into Frame

While a student, Cortez attended events where CSUN alumnus Kevin Olivas ’88 (Journalism) was often a speaker. Olivas, a former radio news reporter, transitioned to nonprofit groups that supported journalists from diverse backgrounds, including the California Chicano News Media Association (CCNMA): Latino Journalists of California.

Cortez caught Olivas’ attention.

“I might have brought doughnuts or something with me just to serve the people who took the time to be there (at the event),” Olivas said. “Then, I would take it out to my car when I was done. And if I got somebody who just voluntarily followed me along and helped me, but also kept asking questions, then I knew I had a winner. My recollection was that Julio did that.”

Cortez showed Olivas his photographs, and in that area, he also knew he had a winner.

At CCNMA, Olivas served as a pipeline for people of color to find opportunities with news organizations across the country — including the Associated Press.

Cortez poses outside of Associated Press headquarters in New York City in 2004. (Courtesy of Julio Cortez)

Olivas recalled AP making a push in 2005 to recruit interns from diverse backgrounds.

“When they were asking if I knew of any good interns, one of the names that came up for me was Julio because of how good he was at taking pictures that told a story,” said Olivas, now the news recruiting manager for the Sinclair Broadcast Group. “He had a really great eye for it, was very inquisitive and seemed dedicated to a career in journalism. He wouldn’t just let the picture speak for itself. He tried to find out something about it to enhance the story.”

Cortez landed a 12-week internship at the Associated Press Chicago bureau. That internship eventually led to a job with the Associated Press — first, eight years at its New Jersey bureau and the past two at its Baltimore office.

During that time, he has covered Super Bowls, Olympics, the aftermath of the Sandy Hook shooting, and the hunt for the Boston Marathon bombers.

The latter shook him but didn’t cause him to hesitate before taking an assignment. He wasn’t married at the time, nor did he have children, so he wasn’t worried about the dangers often associated with his profession.

Things have changed.

Julio met an aspiring photojournalist and high school teacher named Emily. They first connected when Emily, living in Mississippi, reached out to Julio, living in New Jersey at the time, for mentorship.

“It was his sports photography that drew me in,” Emily said. “He just captured the determination of athletes and had great composition to his work.”

Emily, originally from upstate New York, would stop to visit with Julio on trips to see her family in the Tri-State Area.

Mentorship turned to relationship. They got married on June 22, 2017.

Their first boy, Sebastián Cuauhtémoc, was born in 2018. Román Miles followed in 2019.

On January 20, 2020, Cortez was sent on assignment to Richmond, Va., to photograph a rally for gun-rights activists. An estimated 22,000 people gathered, many openly carrying weapons. Cortez recalled seeing one man carrying a 50-caliber gun so large that he had trouble holding it.

Because of the potential danger, as activists protested plans by Virginia’s Democratic leadership to pass gun-control legislation, Cortez wore a helmet for the first time on assignment. He also was issued a gas mask by the Associated Press and learned how to use it.

“That night, I was talking to one of my friends, and she mentioned the rally,” Emily said. “The way she spoke of it, I thought, ‘Oh, wow. This is going to be really dangerous.’ So I made the mistake of looking it up. I googled it. I realized maybe he’s putting himself in harm’s way more than I realized.”

Stepping Up for the Moment

Four months later, on May 26, 2020, Cortez watched the news and saw a viral video from the day before.

Cortez watched TV throughout the day as the name George Floyd became known, and outrage led to protests in Minneapolis. Cortez recalled thinking that the AP should be there to cover this event. But he never thought about being the one to go.

Two days later, at 8 a.m., Cortez’s phone rang at his home in Baltimore. He was told he needed to get to Minneapolis immediately.

AP was sending its own photographers — Cortez and New York City staff photographer John Minchillo — to the scene of what was rapidly becoming history.

Cortez said he would go, but with one condition: He asked for a bulletproof vest. His editor told him he’d find him one, and did. But the vest was in Washington, D.C., and Cortez would have to drive an hour to get there, then fly out of Dulles Airport.

Scared and uncertain, Cortez made the drive.

It gave him time to think.

The scenes of the murder and crescendoing unrest in Minneapolis played through his mind, heightening the anxiety in his body.

Cortez thought about his mortality. He thought of Emily, Sebastián and Román.

Cortez celebrates with his family — sons Román, 1, left. Sebastián, 3, and his wife, Emily, after the announcement of the 2021 Pulitzer Prizes on June 11. (Courtesy of Julio Cortez)

As he drove, his knees were trembling and he was sweating.

Determined to go forward, he spoke to himself to calm his nerves.

The Associated Press had sent him to Minneapolis to do a job. The AP gave him a shot to document one of the most important events of his lifetime. So if he was going to do this, he had to do it right.

Finally, Cortez said something to himself that gave him the courage to go forward. He also thought about the award that is the highest aspiration of those in his profession and how this would show his worthiness as an American.

“F— it,” Cortez said to himself, “let’s go get us a Puli.”

experience

experience