CSUN’s Asian American Studies Celebrates 30 Years of Giving the Community a Voice On Campus

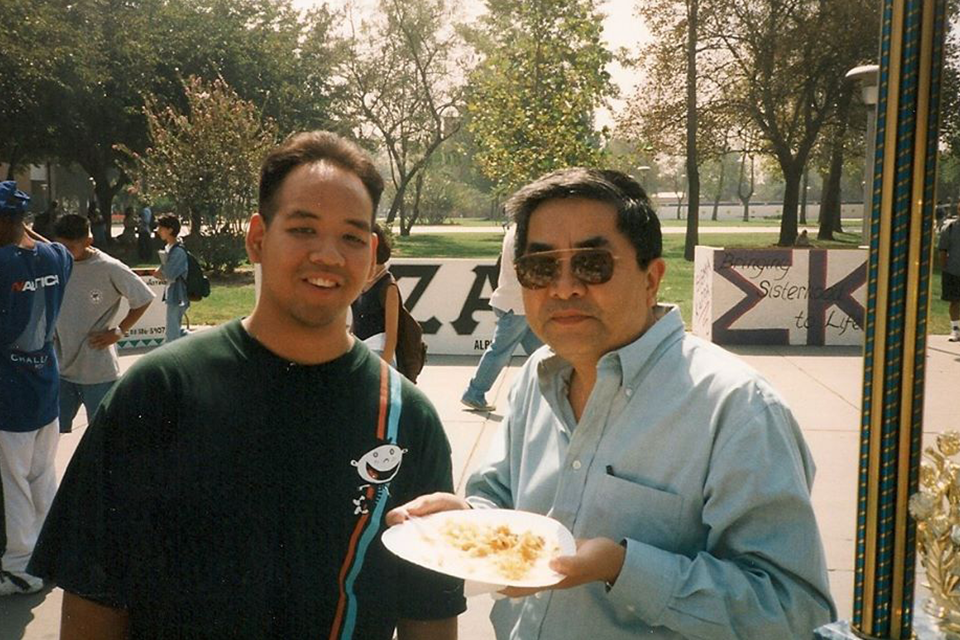

It was barely three months after the 1992 Los Angeles uprising that Allan Aquino, now a professor of Asian American studies at CSUN, first walked onto the campus as a freshman. Though the unrest sprung from police violence against Rodney King, a Black man, the fervor for change in society was shared by Asian Americans.

“By the time I took my first classes at CSUN, the racial tension toward Asian Americans, especially Korean Americans, was fresh in our memories,” Aquino said. “Back then, we didn’t have internet or the technology we have today. We got most of our information from the popular media, TV and radio. And a lot of it was very biased and skewed and unfair in how Asian Americans were represented. So it was up to us [Asian American students] to represent our community the only way we could, which was through our college environment.”

As Aquino and his fellow students sought a more prominent platform for their voices and ideas, they found a home on campus in the newly established Department of Asian American Studies. It was only two years old then, but it was birthed through years of struggle by the Asian American community to establish their own space in academia.

At CSUN, that space has grown, developed and prospered for three decades. This coming academic year, the department is celebrating its 30th anniversary in CSUN’s College of Humanities.

“Part of the struggle for Asian Americans is that we’ve been here a lot longer than people realize,” said Asian American studies professor Teresa Williams León, who was teaching her evening Asian American Women class on April 29, 1992, the very day that the riots erupted in L.A. “We’ve been so invisible, even though today we’re one of the fastest-growing groups. So, in that context, it’s exciting to have this department — where that history and those stories are told, taught and documented.”

Asian Americans marched alongside African Americans and Latinx Americans in the push for ethnic studies in the 1960s. But while Africana studies and Chicana/o studies found their footing at CSUN in 1969, for decades Asian American studies still held onto the dream of having their own department.

As they stayed the course, Asian American faculty organized an ad hoc committee to plan out Asian American studies classes, which were first proposed in 1981. Five years later, Asian American studies made its first CSUN appearance through a single anthropology class taught by professors such as Laura Uba. (This June, upon her retirement, the university honored Uba with professor emerita status.)

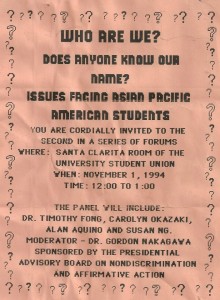

A flyer for the Asian American Studies “Who Are We” event on November 1, 1994. Photo courtesy of Allan Aquino.

Students helped continue the fight by protesting and demonstrating on campus, with leaders such as Gary Mayeda, Keith Lee, Dean Mimura, Gigi Santos and Alfred Tenazas. They shared their testimonies about the need for the department, and some even ardently spent their time putting up posters for the first Asian Pacific Awareness Week, an event made to promote Asian American culture and diversity, in 1989.

Then in 1990, the foundational work laid by the steadfast Matador students and faculty finally came into fruition.

Before former CSUN Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Bob Suzuki signed off, he signed something else first — the document officially establishing the Asian American studies department in the university.

“I strongly supported the creation of the department,” Suzuki said, “because when I myself was teaching the subject, I saw the profound, positive impact it had on my students.”

A Small Department in a Little Trailer

With Kenyon Chan at the helm as chair, the department developed courses about the complex Asian American experience. They hired faculty, including Timothy Fong and Williams León, the department’s first tenure-track hires. By 1992, they established a minor, and by 1997, their own major.

The first years were an uphill battle. On top of a lack of resources for a budding department, they lived through the 1994 Northridge earthquake, which destroyed a number of CSUN buildings and forced Asian American studies — like many at the university — to move to “a little trailer with a copier on [Chan’s] desk,” in front of the CSUN Library, Williams León recalled.

Despite the roadblocks over the past 30 years, the department has persisted for its students, for whom faculty, staff and alumni held their arms open wide, Uba said. “Even when we were in cramped offices,” she said, “there’d be kids just hanging around because this was home.”

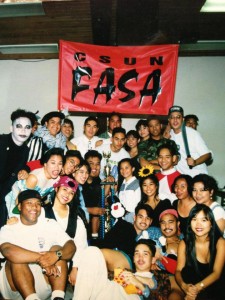

Students enjoy a fun night at a FASA Halloween party in 1995. Photo courtesy of Allan Aquino.

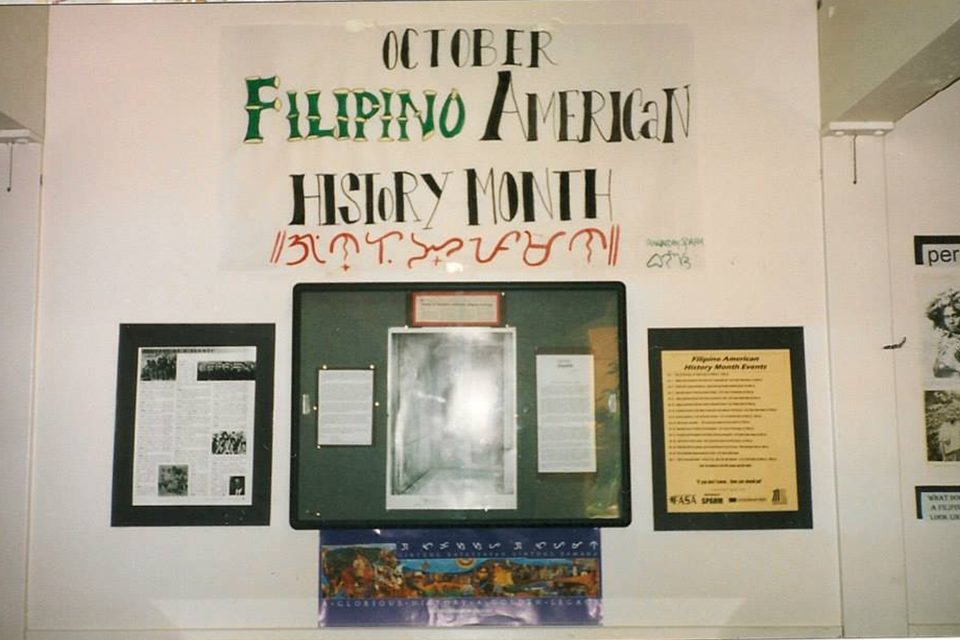

Students themselves have contributed to the success and fortitude of the department. The Asian House, which was renamed the Glenn Omatsu House in 2014 to honor the exceptional professor and mentor, has been the headquarters for a number of student organizations. One of these groups is the Filipino American Student Association (FASA), which was first chartered in 1982.

In fall 1993, FASA organized an event that featured Philip Vera Cruz, a prominent leader in the Filipino American and Asian American movements, to speak to students. Aquino attended that event and was immediately inspired. He said it was because of “these singular, transformative moments” that led him to pursue Asian American scholarship and eventually, to teach at the department at CSUN.

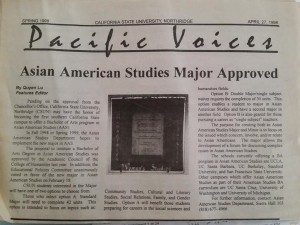

The department supported the publication of an Asian American community-centered newspaper called “Pacific Voices” that reported on departmental milestones and announced community events. It was organized by the Asian Pacific Student Alliance, which “served as a liaison or ‘United Nations’ for all the Asian American student clubs,” Aquino said.

“The heart of the department really is our students,” Williams León said. “They’re the reason why the department exists. They’re the motivating force, why the department keeps going. … We want to be there for our students, to help bring out the best in them and nurture their consciousness. And I hope that they, as they leave our department, will become agents of social change.”

“A Medicine That Raises People Up”

As the department celebrates three decades of thriving at CSUN, it has seven full-time faculty, 15 to 20 part-time lecturers and 12 student clubs with which it’s associated. Programs like the Asian American Studies Pathways Project are also in place to support student success and foster a more active ethnic studies culture at CSUN.

“The founders left a legacy for us to build upon,” said Asian American studies professor Edith Chen. “For a small department, the faculty are doing a lot of innovative stuff.”

Chen is the principal investigator for a National Institutes of Health research study on Asian Americans and health, in collaboration with CSUN health sciences professor Lawrence Chu. It is the first large-scale funded study on Asian Americans and health at CSUN that also supports undergraduate and graduate students who are interested in learning more about the topic.

Chen praised the work of faculty members including Tracy Lachica Buenavista, who recently was recognized for her trailblazing work with undocumented students at the CSUN DREAM Center; Williams León, who brought in new classes on multiracial studies and the intersections of the Asian American identity and sexuality; and Uba, whom Chen called a pioneer for Asian American psychology. She also noted that the department has hired a new professor, Simmy Makhijani, whose work focuses on the solidarity between South Asian Americans and African Americans.

A Pacific Voices issue released on April 27, 1998 announces the approval of the Asian American Studies major in CSUN. Photo courtesy of Allan Aquino.

“The growth of the Asian American studies department over the past 30 years is so remarkable,” said Chan, the inaugural department chair. “It is a testament to the hard work and dedication of faculty, staff and many generations of students.”

Though there are palpable strides in the academic system, “a lot of the issues stay the same,” Aquino said.

The current issues surrounding unjustified violence and systemic racism, Chen said, “remind us of the important work that we do.”

She noted that one of the four police officers involved in the killing of George Floyd, Officer Tou Thao, is Asian American. “We need to have some self-examination within our communities about anti-Black racism and how we might be consciously or subconsciously participating in that,” she said.

Aquino said that as he looks beyond the 30-year milestone of the Department of Asian American Studies, he’s optimistic about the power of ethnic studies to continue to introduce new perspectives and make long-lasting change in society.

“Especially today, it’s very easy to be cynical and doubtful about the state of the world,” Aquino said. “But I’ve been around long enough to see how things do change, to see how the empowerment grows — not like a virus but like medicine that raises people up. So, I’m happy to be a part of this community to this very day because I know what it can do; I know what we can do.”

experience

experience