CSUN Professors Says Seaweed Aquaculture Might be the Next ‘Big Thing’

CSUN marine biologist Janet Kübler holding Laminaria farlowii. Photo courtesy of Janet Kübler.

California’s future may lie in seaweed, specifically kelp.

California State University, Northridge marine biologist Janet Kübler has been awarded a $152,054 grant from the National Sea Grant College Program and her industry partner, The Cultured Abalone Farm in Goleta, Cailf. to develop a seaweed crop that isn’t yet grown by anybody else. If successful, Kübler may have identified a new aquaculture product for the state.

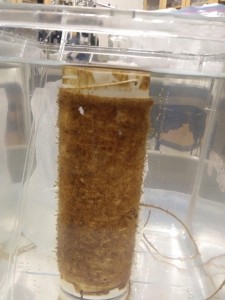

Baby kelp in the nursery. Photo courtesy of Janet Kübler.

“We are part of making a new sustainable economy,” Kübler said. “Some researchers and entrepreneurs are pioneers using what we know about ecology to make an economy where life flourishes. That sounds like a crazy big idea but my part of it is just growing new seaweeds and I can do that.”

What Kübler is growing is a kelp, like giant kelp that make up kelp forests, underwater areas with high density of kelp. Giant kelp are sensitive to warm temperatures, so when we experience warm years — such as El Niño years, which are characterized by the appearance of unusually warm, nutrient-poor water in the Pacific Ocean — there are big diebacks of the kelp forests. However, there are some species native to Southern California that are tolerant of higher ocean water temperatures.

Kübler is taking one of those species – similar to one grown for food in Asia – called golden kombu, known by its scientific name Laminaria farlowii. She is using the golden kombu to develop cultivation techniques to grow the novel, or new, kelp in warming water

“We are optimizing the conditions for producing large crops of golden kombu on the California coast, by first growing them in experimental conditions in the seaweed nursery,” Kübler said.

The depletion of fish stocks are forcing people to depend more on aquaculture – the farming of fish, crustaceans, mollusks, aquatic plants, algae, and other organisms – to provide food for people.

Seaweed aquaculture, Kübler pointed out, requires no fertilizer, freshwater and no landscape. “It’s a big advantage over growing crops on land,” she said.

Kübler noted that there also is a growing interest in growing seaweed for biomass energy – energy generated by living or once-living organisms.

Graham, a seaweed farmer, holding Laminaria farlowii. Photo courtesy of Janet Kübler.

To grow seaweed, an on-land nursery is needed. The seaweed is then planted on “seed string,” a thin fuzzy string that the seaweed spores settle on, in the nursery. The spores are seeded onto a string, 2 millimeters in length. The string is then attached to a 100-foot rope that can resist the ocean waves and support the weight of adult kelps that grow up to 10 feet.

While respecting social distancing recommendations by state and local health officials to control the spread of COVID-19, Kübler said she and her team of researchers, which includes CSUN students, are looking forward to soon organizing California’s first seaweed festival.

“It’s going to be an all-day event,” Kübler said. “We’re going to get all the people who have seaweed related businesses. We’ll have food, music, games, art projects and presentations. It’s going to be fun and full of seaweed!”

For more information and updates on the festival, visit https://californiaseaweedfestival.com/.

The National Sea Grant College program was established by the U.S. Congress in 1966 and works to create and maintain a healthy coastal environment and economy. The Sea Grant network consists of a federal/university partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and 33 university-based programs in every coastal and Great Lakes state, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The network draws on the expertise of more than 3,000 scientists, engineers, public outreach experts, educators and students to help citizens better understand, conserve and utilize America’s coastal resources.

experience

experience