May it Please the Court: CSUN Makes History with Appellate Court Session on Campus

The bailiff banged the gavel, calling out: “All rise!”

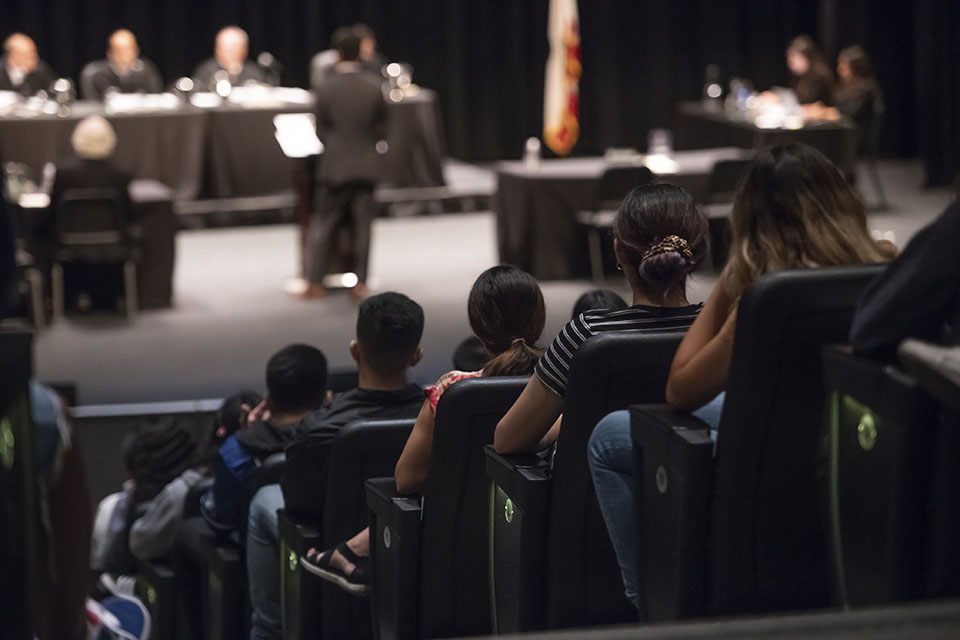

The auditorium filled with the sounds of creaking theater seats and shuffling papers, the squeaking of Vans and Doc Martins soles, as nearly 500 CSUN students and faculty stood, watching in silence as the justices filed to their seats. Robed in black, the justices settled into their chairs.

Court — and class — was in session.

CSUN made judicial history Oct. 16, as the first California State University campus to host a session of the California Court of Appeal, Second Appellate District, Division Five. It’s exceedingly rare for any court to hold a session outside the confines of the traditional courtroom, let alone traveling to a campus. Invited from their usual courtrooms in downtown Los Angeles by CSUN professor and former appellate justice Sandy Kriegler, the justices and the attorneys presenting the day’s cases enthusiastically agreed to the court “road show” of sorts.

Their chief motivation was education — giving hundreds of undergraduates the opportunity to glimpse democracy and the judiciary in action — but also the need for recruitment, diversity and development, to encourage more young people from all backgrounds to pursue careers in the courts, law enforcement, the judiciary and beyond. CSUN, with its young and booming Department of Criminology and Justice Studies and one of the state’s most diverse learning environments, was a natural fit.

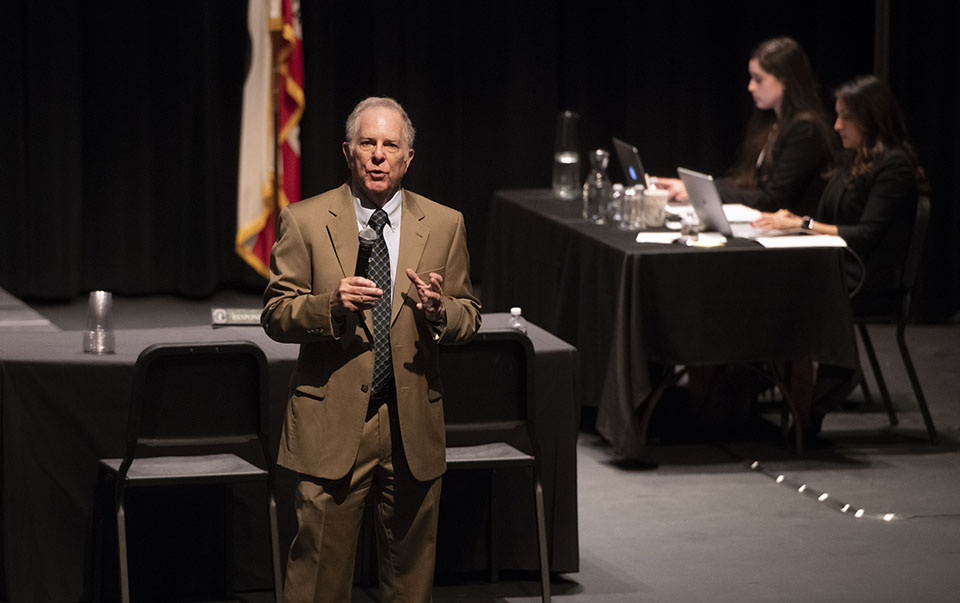

“This is going to be a new experience for most if not all of you,” Kriegler told the audience of students in CSUN’s Plaza del Sol Performance Hall, before the justices filed onto the stage. “This is the second-highest court in the state of California (after the state Supreme Court).”

Before they heard the first of three cases, presiding justice Laurence D. Rubin thanked Kriegler and university officials for making the session possible.

“This is not an easy process to get a state-owned court out to the academics, and a lot of work went into this,” Rubin said, thanking the faculty and staff of CSUN, particularly the Department of Criminology and Justice Studies.

In addition to Rubin, Associate Justice Lamar W. Baker, Associate Justice Carl H. Moor and Associate Justice Dorothy C. Kim participated in the two-hour session, where they heard oral arguments for three civil and criminal cases. As they signed in with their professors for class credit, the CSUN students received short, written summaries of the cases they would hear — including a petition from a man seeking early parole based on a recently passed state law under Prop. 57, which provided for early release for some non-violent offenders.

Appellate courts differ from the trial courts most Americans know from TV, films, jury duty or other personal experience: There are no witnesses, no defendants present, no jury. Appellate court justices review the records of the trial courts for error.

During the Oct. 16 session, CSUN students had the opportunity to hear in real-world context legal words and concepts such as briefs, State Constitution, non-violent offender, legislators, statute and due process.

On stage, a table on a short dais made up the justices’ “bench,” and the ad hoc courtroom included a podium for the attorneys, one table for each seated legal team, the bailiff’s table at stage left and the court clerks’ table at stage right.

After the arguments in the three cases concluded, the justices filed out, removed their robes and returned to the stage in suits to take a number of questions from students in the audience.

“As you could tell from the arguments, we’re not used to fielding questions,” one of the justices quipped. “We’re used to giving questions.”

Students’ questions ranged from how the justices make their decisions to advice for those considering law school and what judges do to decompress in their free time.

In response to one student’s question about whether it’s difficult to stay impartial, Moor said: “One becomes a judge and gives up being a lawyer because one likes the position of being neutral, of listening to both sides. After a while, you just get used to it.”

As in all courts, those in attendance were forbidden from speaking during proceedings. Relieved to be able to speak after the two-hour session, students buzzed afterward with questions and comments.

“I was told by my professor that this is almost a once-in-a-lifetime experience, so I knew I had to be here,” said senior and criminology and justice studies major Steven Feit. “I was very excited to come, and it was really interesting.”

experience

experience