CSUN Pioneer Leaves a Legacy to Support Minority Students in Engineering and Computer Science

Rick Ratcliffe, pictured next to an Army veterans photo exhibit at Belmont Village in Hollywood. Photo courtesy of Kelsey Gordon and Gretchen Edwards.

As the first African American to serve as a dean of engineering in the California State University system, Alfonso F. “Rick” Ratcliffe felt obligated — and made it his life’s mission — to support minority students in engineering. Ratcliffe devoted most of his career, first as professor and then eventually as dean of CSUN’s College of Engineering and Computer Science, to that mission. He also made sure that legacy would endure long after he walked the university’s halls.

Ratcliffe, who died in November 2020, made a planned gift to CSUN to establish an endowment that will provide annual scholarships to promising undergraduate students, especially first-generation college students, studying engineering and computer science.

The Dr. Rick and Dolores Ratcliffe Scholarship Endowment will support students in the college with demonstrated financial need and leadership or participation in CSUN’s student clubs that support minority students in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). Those clubs include the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers, National Society of Black Engineers, Society for Women Engineers, Society of Advancement of Chicanos/Native Americans in Science at CSUN, and the League of Asian and Pacific Islander Student Organization.

“Being the first and a pioneer didn’t matter as much to him — it was the students that mattered to him,” said Ratcliffe’s niece, Gretchen Gordon. “He got an energy from the students. That was the reward — helping them get an education and better themselves. He was so approachable, and he was so interested in what they wanted to do.

“He was very specific in his trust about how the money was to be used: to benefit the school of engineering, underprivileged youth, people who are the first person in their family to go to college,” said Gordon, who along with her husband and Ratcliffe’s nephew, Kelsey Gordon, serve as executors of Ratcliffe’s estate. “STEM was first and foremost for him, and supporting minorities. That was the way they lived their life — he and (his wife), Dolores. They gave their lives to those causes.”

Rick Ratcliffe served as dean of the College of Engineering and Computer Science for more than a decade in the 1980s and early ’90s. He joined CSUN’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in 1975, and he was appointed chair in 1978. He rose to become associate dean in 1980 and then dean in 1981. He retired in 1992, when the university granted him emeritus status.

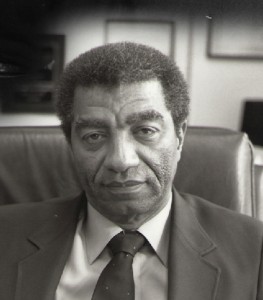

Rick Ratcliffe, during his time as dean of CSUN’s College of Engineering and Computer Science.

One of the first African American deans of a non-HBCU engineering school in the nation, Ratcliffe was considered a role model for many young scholars. Based on his personal experience, as well as his wife’s, Kelsey Gordon said, his uncle understood that many college students don’t have the backing of their parents — they must support themselves through university.

“He was very encouraging to my daughter and other people in the family to go to college and pursue their dreams,” Kelsey Gordon said. “And whenever anyone in the family was having any problems with math, whether it was algebra or any level, he was the go-to person in the family. He’d help anyone in our family. He loved teaching in every way.”

During his tenure as dean, Ratcliffe was instrumental in the success of the college’s Minority Engineering Program, as well as its relationships with industry partners. He remained involved with the college during his retirement and served as a member of its Industry Advisory Board until recent years.

“We expect [students] to go out of here ready to start producing a product the day they walk out,” Ratcliffe said in an interview during his time as dean. “We want them to understand the fundamentals of their chosen field.”

The Ratcliffes’ assistance to students also hit closer to home. In 1983, Rick met George Zhao ’85 (M.S., Mechanical Engineering), an international exchange student from China who was brand-new to CSUN at the time, and a little lost in his new environment. The Ratcliffes took Zhao under their wings, and they would later unofficially adopt him as their son, he said. Zhao went on to work as an engineer in construction in the Los Angeles area, and he never forgot their kindness during his student days.

“Every Thanksgiving, every Mother’s Day, we were together,” said Zhao, who lives in Walnut. “I have a son and daughter, and they always knew, every holiday — we would go see Grandpa Rick and Grandma Dolores.

“Supporting minority students in engineering was very important to them,” he said. “They knew that education can change a whole family. It was a big honor for CSUN to have a person like Rick. He was so knowledgeable. I was so lucky to know him and have him as my Dad. And I was not the only person he helped — he helped so many people.”

Among his many groundbreaking accomplishments, Ratcliffe was responsible for hiring more women into CSUN’s engineering programs than all other CSUs combined.

“I did not have the privilege to personally meet Dean Emeritus Ratcliffe, but he is remembered fondly in the college by those who knew him,” said Houssam Toutanji, dean of the College of Engineering and Computer Science. “Dean Ratcliffe’s recent passing was greatly felt in the college, but we are grateful to see his thoughtfulness and the confidence he had in the college and its programs through this endowment, which will forever honor his memory and that of Dolores, his wife. I would have liked to meet Dean Ratcliffe. He is an inspiration! He dedicated his life to helping students and continues to do so now that he is not with us, through this generous gift that will benefit future generations of students.”

Ratcliffe grew up in St. Louis, where schools were still segregated at the time, and — after graduating from high school at age 15 — moved to Los Angeles to live with an aunt and attend college. After serving in the U.S. Army, Ratcliffe took advantage of the G.I. Bill and completed a bachelor’s degree in physics from UCLA. He also went on to earn a master’s and a doctorate in engineering from UCLA. His academic areas of interest included control systems theory, dynamics and applied mathematics.

An undated family photo of Rick and Dolores Ratcliffe. Courtesy of Kelsey Gordon and Gretchen Edwards.

In an interview, Ratcliffe once noted that he had wanted to build bridges since he was a boy, but because engineering jobs were “something rare” for Blacks at that time, he spent several years after college doing other jobs. His early engineering work included time as a test engineer at Rototest Laboratories. Before turning to teaching, he worked in design and manufacturing at Mattel, Inc. — where he helped design the first musical doll.

Dolores Ratcliffe, who passed away several years before her husband, was an entrepreneur, author and owner of Corita Communications, Inc., as well as past national president of the Association of Black Women Entrepreneurs. She had been honored by the city of Los Angeles and myriad organizations for her work supporting minority women in business, and she taught part-time for three years in CSUN’s David Nazarian College of Business and Economics.

experience

experience